Where Do Democrats Go from Here? Pt. 3: What a Viral Video About the Drake-Kendrick Lamar Beef Can Teach Democrats About Political Communication

PLUS: Does the NBA have a 3-point problem?

Democrats’ alleged messaging failure during the 2024 election is the subtext of a lot of campaign postmortems, which typically begin with a writer a.) Lamenting Democrats’ failure to connect with working-class and swing voters, followed by b.) An admission that Biden actually enacted a lot of policies that benefitted working-class and swing voters and that Harris actually geared much of her campaign toward those voters as well, before concluding c.) Democrats just didn’t do a good enough job selling working-class and swing voters on their record and proposals.

OK, fine, but I must say it’s infuriating to read articles like that because they begin by suggesting Democrats are screwing up on matters of substance before concluding it’s all just a matter of style. I’m someone who happens to believe the contents of a book ought to count for a lot more than its cover, so when I’m led to believe Democrats aren’t delivering on the things that make a real difference in the lives of Americans only to be told, no, voters just don’t understand that Democrats are doing that, it kind of drives me nuts.

None of that is to suggest Democrats don’t have room to improve on the substance of these issues. I wrote a bit about that last week. Nor is it to say working-class and swing voters don’t vote on substance. A lot of those voters were hit hard by rising prices following the pandemic, blamed it on the sitting president, and voted for the candidate from the alternate party. Now, did those voters take the alternate candidate’s inflationary policy proposals into account? I’d say they didn’t. But I can’t say substance didn’t factor into their decision. Fortunately, if inflation is the substantive yet election-specific issue that either tipped those voters to Trump or caused a lot of dispirited Democrats to stay home, then it suggests many of those voters will be back in play for Democrats in future elections.

The good news is that if this really is just a matter of style over substance, that’s a much easier issue for Democrats to fix. It’s hard for parties, which are coalitions of interest and ideological groups, to overhaul their policy platforms. But parties can emphasize or deemphasize platform planks and adjust their messaging and image to better connect with voters. They can even turn to candidates who are adept at communicating those particular messages and who can lean on their biographies, personalities, and records to build trust and ingratiate themselves with voters.1

Admittedly, that’s some pretty superficial stuff. I’m constantly reminding myself not to overemphasize the role image and messaging play in politics. When pundits get caught up in things like debate performance, political ads, and speechifying, they treat politics as performance art; turn political molehills into mountains; and overlook the more significant personal, political, and economic factors that determine people’s opinions. The idea that a speech, slogan, or gesture can sway the masses amounts to a desperate lashing-out by people who mistakenly believe a verbal and performative stratagem a la The West Wing can amount to a political checkmate.

(BTW, if you really want to understand how the media affect politics, you need to turn to Marshall McLuhan, who famously wrote, “The medium is the message.” What that means is that it’s not necessarily the content of a message that matters, but rather how the medium itself ultimately shapes society. For instance, when social media are the hot, dominant media of the era, that era will probably end up with politicians whose personal traits allow them to excel in a world that is shaped by and reflects social media; in other words, politicians who are pithy, impulsive, shameless, inattentive, self-indulgent, unconcerned with detail or accuracy, hyperbolic, narcissistic, and tribal. We’ll return to this in a bit.)

Yet even though it is easy to overestimate the effect political messaging has on political outcomes, politicians can’t ignore the art of political communication. Unfortunately, Democrats did not do a good job at that this year. What makes that even more infuriating is the fact that this race was incredibly close. It’s likely the 1% of American voters who would have needed to flip their vote from Trump to Harris to make Harris the victor could have been swayed with a better message.

A big share of the blame belongs to President Biden, who struggled mightily over his four years in office to effectively communicate with the American people. By Election Day, voters knew little about his administration’s accomplishments or how Republicans worked to thwart him. Some (myself included) will say Biden wisely eschewed a bully pulpit strategy aimed at winning over the public in favor of an inside game that resulted in a surprisingly productive legislative record. That does go a long way toward explaining Biden’s achievements, but presidents can’t forego the victory laps that let voters know who deserves credit for delivering on their priorities. Others may be inclined to blame Biden’s struggles on an inattentive public, but while that’s certainly an issue (more about that later) presidents need to be out there engaging the public rather than assuming their good deeds will speak for themselves.

The Harris campaign also made its share of mistakes in terms of both communication and communication strategy. Harris should not have taken the weekend after the DNC off but rather hit the campaign trail to keep her momentum going and to make sure Trump never had the spotlight to himself. (Trump appears more acceptable when his opponents aren’t there to serve as a counterpoint.) Harris and running mate Tim Walz also vanished from earned media for long stretches of time. And frankly, Harris isn’t a great communicator. She did a better than anticipated job, and she certainly had her moments, but she often looked uncomfortable discussing issues that weren’t in her wheelhouse or that she didn’t feel passionately about.

As far as messaging is concerned, Harris never devised a good way to address inflation or highlight the inflationary potential of Trump’s policies; instead, whenever the topic came up, she came across as evasive. (Pro tip: Even though political consultants advise candidates to talk about issues they poll well on and avoid topics they poll poorly on, candidates still need to come up with ways to address issues they’d rather not talk about. There’s no way to dodge it. Trump, for instance, had an answer for abortion. Harris didn’t really have an answer for inflation.) Similarly, Harris never put together a good response for what she would have done differently than Biden even though she knew that question was coming. (How about, “I would have acted sooner on inflation”? If she was worried about appearing disloyal to Biden, that answer at least wouldn’t have broken with administration policy. Or maybe “I’d have been tougher on Netanyahu”? Biden could have used that response as leverage with Israel.)

Most notoriously, Democrats struggled to connect with voters online. That’s a huge embarrassment, as Democrats had pioneered the use of social media as a mobilizing tool in the 00s. For this election, however, Trump and the Republicans dominated the social media ecosystem. You can attribute that to Facebook/Meta’s decision to throttle political content, Elon Musk turning Twitter/X into a conservative hellscape, and Trump’s own TruthSocial site, but outside some TikTok videos that took the platform by storm shortly after Harris became the nominee in July, there was just no buzz surrounding Democrats online. Maybe that’s simply a reflection of Republicans’ greater enthusiasm for Trump, but the GOP’s presence in those online spaces was critical, particularly among young men.

Even more problematic, Democrats failed to recognize the power of podcasts until it was too late. That to me is unforgivable: I personally don’t listen to podcasts (I can’t do that and write at the same time) but their influence on public discourse is obvious. Podcasts are also an easy way to reach target audiences and, when they’re non-political in nature, to connect with voters who may not be paying much attention to politics. Maybe the Biden campaign had not explored the possibility of going onto podcasts, leaving the Harris campaign to play catch-up, or maybe Harris herself was not comfortable on podcasts, but if that’s the case, it speaks poorly of the candidates themselves.2

Democrats face a number of challenges when it comes to social media, including the MAGAfication and Muskification of Twitter. A major challenge, however, is tied up in the nature of social media itself. As mentioned earlier, as media, social media have a tendency to generate pithy, hyperbolic content. Individual expression is more valued than veracity, but given the personalized nature of the medium, people often trust what they see on social media more than what they encounter in more remote traditional media. Engagement with a message on social media is also simultaneously fleeting (consuming a message may take no more than a few seconds) and deep (social media algorithms ensure users will see more messages similar to those they have already consumed, connecting them to other likeminded users in the process.) It turns our already degraded political rhetoric into an endless series of soundbites bouncing around an echo chamber.

Polls throughout the 2024 election season showed low-information voters—that is, voters who don’t pay much attention to politics and only encounter it in passing—tend to get their news from social media, which they consume casually and often inadvertently. These voters overwhelmingly favored Trump. (High-information voters—voters who seek out political news—leaned toward Harris.) While Trump deliberately courted low-information voters by venturing into non-traditional media spaces (Harris, on the other hand, emphasized traditional media appearances) Trump and the MAGA movement are also notoriously “online” and have a knack for leveraging social media to their political advantage. Consequently, it shouldn’t be surprising Trump was able to win over so many low-information voters.

While Democrats also have a presence on social media, it’s a less natural fit for them. As members of a party that believes government can be used to improve people’s lives, Democrats are wonky by nature, leading them to dwell on detailed policies aimed at addressing nuanced public problems. Whereas Republican proposals tend to be more visceral in nature, Democratic proposals (and their defenses of them) are often more cerebral. It is therefore harder for Democrats to make their case to an American public with a short attention span and little interest in detail, let alone connect with low-information voters used to digesting information in messages bound by character limits.

In politics, it’s often said if you’re explaining, you’re losing. There’s some truth to that. But in politics these days—and frequently on social media—there’s little time to express even a minimally complex thought, which is a problem given the complexity of the challenges we face.3 Additionally, Democrats need to be able to explain if they hope to convince the public on the merits of their ideas. Therefore, if Democrats want to remain competitive in a political world shaped by social media, they need to come up with ways to explain their ideas to low-information voters on social media platforms.

I might have a model.

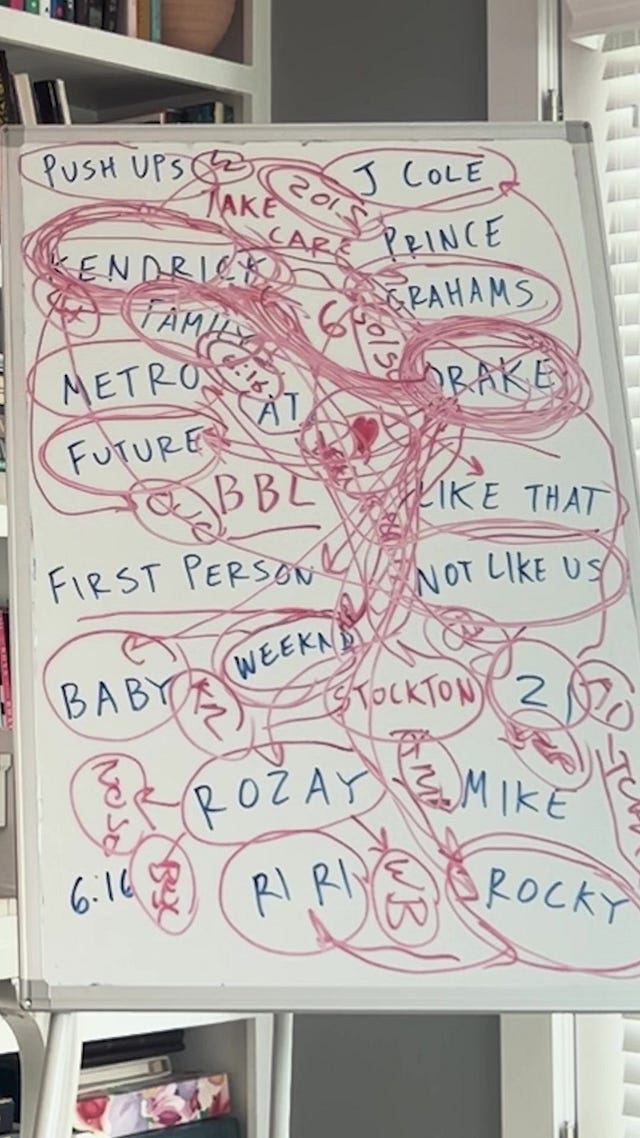

As you may recall, last spring, the rappers Kendrick Lamar and Drake engaged in a high-profile beef that spawned a number of diss tracks, including Lamar’s “Not Like Us”, which multiple publications have placed near the top of year-end best-of lists. I’m not going to get into the details of all this; if you want, you can read about it here. Anyway, the feud generated a lot of public interest along with a lot of confusion, so people began posting content online to explain the beef. (For instance, Tom Hanks reached out for an explanation to his son Chet, who posted their text exchange on Instagram.) The following video is an explainer produced and shared by a TikTok user named Rudeboy Brody (who has made similar videos on other topics):

While this video is intended as a work of humor, it succeeds so well as an explainer not only because it’s funny and fast-paced but because it features both a teacher and a student. When it’s just one person doing the explaining, a video like this can come across as preachy or condescending. With two people present, the lecture turns into an exchange, which allows the explainer to signal to the viewer he’s not out to prove how smart he is but instead to help people understand a confusing subject. The explainer gains further credibility with the viewer by asking the student questions: He asks his mother if she knows who Rick Ross is and if she “gets it” (a check for understanding); if she thinks J. Cole made a good decision (allowing her to opine and share her own thoughts); and who she thinks won the beef (allowing her to reflect on everything she’s learned.) All of this makes the student—and by extension, the viewer—the focal point of the video.

As the viewer’s surrogate, the explainer’s mother is a model student. She admits right away that the beef is “confusing” and that she “[does] not get it.” Yet she isn’t clueless: She demonstrates she does possess some knowledge about the subject when she correctly states Lamar won a Pulitzer Prize and that Drake is biracial. She’s clearly following along and engaged, correctly identifying the source of Lamar’s beef with Drake and remarking that it’s all “fascinating.”

There are a few other things she does, however, that are absolutely critical as the viewer’s surrogate. First of all, she voices her opinions, and does so frankly (i.e., “He’s got a big ego, they all do,” “These guys just do whatever the hell they want,” “Drake needs to relax,” and “Everything is much ado about nothing.”) Secondly, she asks questions. Sometimes the question clarifies something the explainer states, (i.e., “What’s [J. Cole’s] mistake?” which she quickly realizes the answer to.) At other times the questions are rhetorical (i.e., “Why would he do that?”). A few times she even wonders if something is “true,” which allows some skepticism to creep into the exchange while signaling she might need some more convincing. At one point, she relates to the people involved, stating, “I would do the same thing.” And finally, near the end, she says she “wants to hear all this music,” indicating she would like to learn more. These are all critical moves because by demonstrating that the student is an independent thinker, the maker of the video indicates they respect the viewer’s independence of thought as well. That in turn earns the maker of the video the viewer’s respect and makes it more likely the viewer will take the content of the video seriously.

Again, I know that’s just a silly video that’s practically making fun of explainer videos, but I think it’s also a good model for how Democrats could use social media to communicate with low-information voters. Imagine a video like that but on the subject of inflation featuring a couple of bros. Such a video could help explain why prices are high around the world (and probably aren’t going down) how the Biden administration worked to arrest inflation, why egg prices are uniquely high (and could come down) and how Trump’s policies could reignite inflation. The video wouldn’t need to be an authentic exchange between someone who understands the subject and someone who doesn’t. It could be done purely in the spirit of entertainment. What matters more is seeing two people—one with knowledge, another who knows a little bit about the subject but is curious, inquisitive, and opinionated—work through the issue together.

The basic problem Democrats encountered this year when it came to inflation was that Republicans could simply state “prices rose on Biden’s watch” while Democrats could not reply with as direct and concise a response. What was needed—as is so often the case with Democrats—was an explanation. Yet rather than offer an explanation, Democrats instead chose to avoid talking about what turned out to be the number one issue on voters’ minds. That’s just not a winning strategy. A video about inflation modeled on the one above about the Kendrick Lamar-Drake beef aimed at low-information voters could have helped mitigate the damage. In an election as close as this one was, deflating that issue even slightly could have made all the difference. It wasn’t just a failure to communicate, but a failure of imagination.

Garbage Time: Does the NBA Have a 3-Point Problem?

(Garbage Time theme song here)

Remember Larry Bird? Yeah, he was a great player. Anyway, Bird was probably the first NBA star associated with the three-point shot, which was only introduced to the league for the 1979-80 season, which also happened to be Bird’s rookie campaign. Bird only took 143 three-pointers that season for the Celtics (an average of 1.7 3-point shots per game) and made 58 of them, good for a smoking 40.6%. The number of 3-point shots he attempted and his 3-point shooting percentage both fell significantly over the next four seasons (he totaled his best numbers from behind the arc during that stretch in 1982-83, when he went 22-77 for a dismal 28.6%) but thereafter he became a prolific 3-point scorer. You can argue over which of Bird’s seasons was his best, but I’m just going to pull up the numbers from his 1985-86 season, which is when Bird won his third consecutive MVP Award and led one of the greatest single-season teams of all-time to an NBA championship. That year, Bird led the league in 3PA (194) and made a league-leading 82 of them, which comes out to a 42.3% average. Two years later, Electronic Arts would release the video game Jordan vs. Bird: One on One, which included a slam-dunk contest mini-game featuring Michael Jordan and a three-point-shooting contest featuring Bird.

Jump to the 2024-25 NBA season. (These numbers are from mid-week when I was writing this, so they aren’t up-to-date.) The league leader in 3PA is Jayson Tatum, who, like Bird, is a career-long Celtic and an NBA champion. Through the first 23 games of the NBA’s 82-game season, Tatum has already attempted 242 3-pointers, which is 5 more than Bird shot during the entire 1987-88 season, his single-season peak for 3PAs. Tatum has made 88 of those shots (ten shy of Bird’s single-season high) resulting in a fairly pedestrian 36.4% shooting percentage. That’s still a lot of threes, though. (The league-leader in 3-point shots made is Anthony Edwards of the Minnesota Timberwolves with 103. Norman Powell of the Los Angeles Clippers leads the way in 3P% among players who have attempted at least 100 3-pointers at 48.6% [69-142]. LeMelo Ball of the Charlotte Hornets is the league-leader in 3-pointers-made per game at 4.7.)

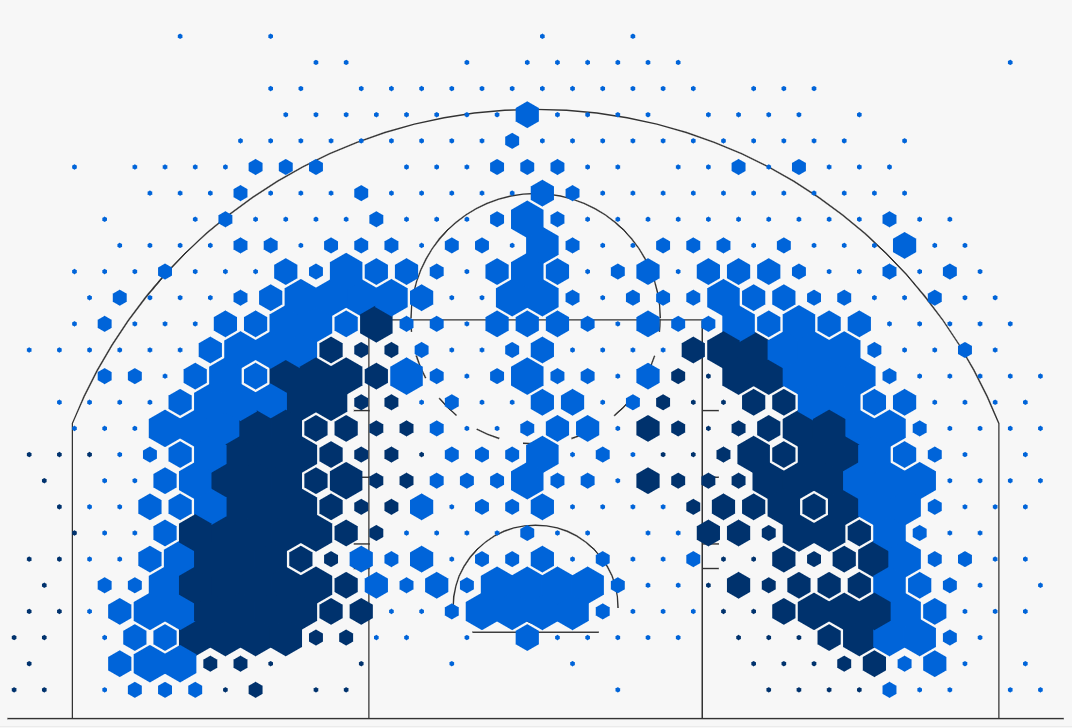

As a team, the Celtics (19-5, 2nd in the Eastern Conference) are shooting the three at a ridiculous rate. Boston has attempted a league-high 1,234 three-pointers this season and drained 37% of them, good for 13th in the league. They also lead the NBA in three-pointers made (456). (For the record, the Cleveland Cavaliers lead the league in 3P% at 40.4%.) Even crazier, the Celtics are averaging 51.4 three-point attempts per game, which is producing shot charts like the one pictured at the beginning of this article. That game between Boston and the Chicago Bulls, who average the second-most threes per game at 43.5, resulted in a combined grand total of (depending on how you want to count it) 9-12 midrange shots, or shots taken outside the lane but within the three-point arc.

During the 1979-80 NBA season, when the NBA instituted the three-point line in order to unclog the lane, spread out defenses, and create runways for dunkers, teams took an average of 2.8 three-point shots per game. By the 1985-86 season, when three-pointers will still considered risky and perimeter shooting was mainly left up to guards, that number had only increased to 3.3 shots per game. When Jordan and the Bulls began the second of their threepeats in the 1995-96 season, the number of 3PAs per game had leapt to 16.0. That number hadn’t risen much higher (18.4) by the time LeBron James won the first of his championships with the Miami Heat in 2011-12. From that point on, though, there’s a noticeable increase in attempts per game each season, getting up to 29.0 when Splash Brothers Steph Curry and Klay Thompson collected their third title with the Golden State Warriors in 2017-18. (Interestingly, the Warriors only took 28.9 threes per game that season, which was ever-so-slightly less than the league average, although they led the league in 3P% at 39.1%) So far this season, the average team is jacking up 37.5 threes per game and making them at a 36.0% rate (which is roughly how well players overall have shot from deep for the past 10-15 years.)

That players are shooting a lot more three-pointers than they did before Curry came into the league shouldn’t surprise even the most casual of NBA fans. But it’s not only sharpshooting guards like Curry, Damian Lillard, and James Harden driving the trend. Stretch-4 power forwards and centers have added the shot to their arsenal as a way to draw rim-protecting big-men away from the basket. Seven-footers without a reliable outside shot are practically a liability these days.

Some are wondering now, however, if it’s gotten to the point where players are shooting too many threes. The concern is aesthetic: Too many players on fast breaks pulling up for three-point jumpers rather than taking it to the rim; star players like Edwards and Ja Morant foregoing soul-crushing dunks in favor of long-range bombs; cut, kick, and swing offenses that are just searching for open shots rather than challenging defenders one-on-one; centers lingering outside the arc rather than fighting for position in the post; the loss of the mid-range game, where Jordan and Kobe Bryant devoured opponents; and a bland product that boils down to a player either taking a shot from deep or at the rim. There’s even concern the league’s devotion to the three is to blame for this year’s dip in viewership, although there are all kinds of factors that could account for that.

There’s a reason players shoot a lot of three-pointers: It’s a highly-efficient shot. The difference between a two-point field goal and a three-point field goal is only one point, but percentage-wise, a three-pointer is worth 50% more than a non-three-point shot. That’s a lot. Of course, three-pointers are shot from distance, which makes them hard to make, but if a player drains one-third of them (say, 100 out of 300 shots, for 300 points) as good shooters do, they’re doing as well as a player who makes half of their two-point field goals (150 out of 300 shots, for 300 points).

Just to put that into perspective, of all the players who have played a statistically significant number of games in the NBA or ABA over the past 75+ years, only 162 of them have a field goal percentage of 50% or better over the course of their career, and most of those players were centers or power forwards who played near the rim. (The career leader in field goal percentage is Michael Deandre Jordan [67.4%] who spent a good chunk of his time in the NBA on the receiving end of alley oops from Chris Paul. The other Jordan shot 49.7%; Bryant shot 44.7%; Bird shot 49.6%.) On the other hand, there are a ton of players in NBA/ABA history who have shot better than 33.3% from behind the arc. I don’t know how many exactly because the list at Basketball-Reference.com starts at Steve Kerr (45.4%) and stops 250 players later at Donovan Mitchell, whose career 3P% is 36.8%.

The problem with the two-point shot is that the further a player shoots from the basket—that is, the further the player is from slamming it through the hoop for an all but guaranteed two points—the more likely it is they’re going to miss. A fifteen-foot jump shot therefore is a high-risk, low-reward proposition. Statistical analysis tells us that rather than take that shot, players should instead either try to get fifteen feet closer to the rim or back up about nine feet to increase the value of the shot by 50%.

Is a basketball league featuring a lot of dunks and three-pointers really a problem, though? Those are two things I want to see happen a lot when I watch a game, along with fast breaks, slick passing, and close fourth quarters. Things I don’t want to see: Centers banging up against each other under the basket, players settling for elbow jumpers, and Kobe clones draining the shot clock as they wait to see if the defense is sending help. In other words, the kind of basketball that prevailed when teams shot fewer three-pointers. So I guess I’m fine with the game as it is right now.

But I get the argument about aesthetics. The Celtics, with their drive to the basket/kick it out/swing it around the arc offense, can get kind of boring to watch. It’s also mind-numbing when teams start trading top-of-the-key threes on successive possessions without ever getting into their offensive sets. Sometimes it can look like players are just running shuttle drills between the free-throw lines.

People have floated various proposals to address this issue. Perhaps the most intuitive remedy is to simply move the three-point line back a few feet. That would probably lower shooting percentages and discourage a swath of players from cranking up threes, but my guess is players would eventually adapt. It’s still worth considering. As far as the math goes, players league-wide really should only be hitting the three at a 33.3% clip. To keep up, maybe the NBA should adjust the three-point line every season.

Another idea is to either eliminate the corner three or widen the court so the three-point arc is the same distance from the basket at all points in the half-court. Currently in the NBA, the three-point line is 18 inches closer to the basket in the corners than everywhere else. Players love taking advantage of the shorter distance: Today, nearly 10% of all shots come from the corner, and players hit them at a higher rate than other threes (although the fact players are more often set when they receive the ball in the corner and can rely on muscle memory to hit that particular shot probably helps as well.) Curry has hit corner threes at an astonishing 60% rate.

But I’m not sure these are good solution. Eliminating the corner three is a terrible idea, as it would create offensive dead spots there and crowd defenses toward the lane. Widening the court makes some sense, but it might also make it harder for a player to defend the corner three, or, alternately, make it harder for a corner defender to help on a drive to the rim. I’d like to know more about what effect widening the court might have on the game, but the cure could turn out worse than the disease.

Others have proposed changing the values of shots, by, for example, making dunks worth three points; reconfiguring the court to add a four-point shot; or making two-point shots worth three points and three-point shots worth four points. My crazy idea: All shots become worth two points in a quarter after a team misses, say, 5 three-pointers during that quarter. Golden State coach Steve Kerr would never allow Draymond Green to shoot a three again. Would that make it too difficult for teams to catch up if they fell behind, however? Maybe the rule wouldn’t apply in the fourth quarter or at the end of halves. Maybe there would be a way for teams to reactivate the three-point line. Or maybe this is making a fairly straightforward game way too complicated.

I know we live in an age of sports analytics, but perhaps the way this problem fixes itself is for teams to rediscover the midrange. Of course, the NBA team this season that takes the most mid-range shots per game—the Sacramento Kings—is currently 13-13 and in 12th place in the Western Conference, although they do have a better point differential than five of the next six teams ahead of them in the standings. But maybe a generation of good shooters who keep encountering stingy perimeter and interior defenses will eventually conclude they need to put the ten-foot jump shot back into their bag. And once that happens, we’ll likely start pining for the days when NBA players let the three fly.

Exit Music: “Forget Me Nots” by Patrice Rushen (1982, Straight from the Heart)

Although I do worry that when it comes to image, there are too many voters in this country who look at the Democrats, see a party that not only includes urban residents, racial minorities, and women but lets them be in charge, and conclude that’s a club they don’t want to be members of. That’s an image “problem” Democrats can’t fix without betraying core principles.

I feel compelled to say this, however: My gut tells me Harris was right to avoid Joe Rogan. Yes, his show has a massive reach, particularly among young men, but the set-up felt like a trap. What was Harris going to do if she went on his show for a three-hour interview only for Rogan to say forty-five minutes into it that he’d heard enough and that he was endorsing Trump? Was she going to sit there for another two hours as he complained about the Biden administration’s opposition to ivermectin as a treatment for COVID? At least Harris’s FOX News interview with Bret Baier, during which he interrupted her repeatedly, only lasted about ten minutes. Also, while we’re on the topic of Joe Rogan, I saw an article the other day claiming he is the new mainstream media. Really? Is Rogan reporting on the fall of the Assad regime in Syria? The attempted coup in South Korea? The collapse of the French government? Does he have an investigative reporting team? Who are his fact checkers? Has he ever invited more than one woman onto his show as a guest per month? If Joe Rogan is the mainstream media, either people have no idea what “mainstream media” means or we’re screwed.

Although I ought to admit this: I’m surprised podcasts are so popular given their length. “The Joe Rogan Show” typically lasts about two-and-a-half hours. I’m not sure how to reconcile what I consider Americans’ short attention spans with popular long-form media. One thought: Are people paying close attention to these podcasts?