What the End of Roe v. Wade Reveals About American Democracy

Plus: A review of FX on Hulu's "The Bear"

The fury of the left’s reaction isn’t merely about guns and abortion. It reflects their grief at having lost the Court as the vehicle for achieving policy goals they can’t get through legislatures. The cultural victories they achieved by judicial fiat will now have to be won by persuading voters. We understand their frustration, but they ought to try democracy for a change. They might even win the debate over abortion.—Wall Street Journal editorial

Anyone who’s taken a course in constitutional law knows Roe v. Wade was far from model jurisprudence. It hangs on an expansive reading of the Fourteenth Amendment (“No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law”) and, to a lesser extent, the Ninth Amendment (“The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people”), and applies the “right to privacy” explicated in the 1965 case Griswold v. Connecticut (which found married couples have the liberty to buy and use contraception) to abortion. I can follow the Court’s logic from the Fourteenth and Ninth Amendments to Griswold—the Constitution as a document does seem aimed at keeping the government out of people’s private affairs—but abortion is trickier because it involves a potential human life, meaning more than the privacy of the pregnant person1 is conceivably in play.

Roe acknowledges as much, so it finds people have a right to an abortion but that that right is not absolute and must be balanced against the government’s interests in protecting maternal health and the life of the fetus. The obvious problem is it’s not clear when a pregnant person’s privacy ends and the government’s interests in protecting a fetus begins. The answer—conception, detection of a fetal heartbeat, quickening (when a pregnant person can feel the fetus moving), viability (when a fetus can survive outside the womb), birth, etc.—involves both scientific and moral reasoning as well as a whole lot of ambiguity. If Roe just left it up to the states to sort it out for themselves, the Court would have found itself preoccupied with cases based on various states’ attempts to strike that balance. Consequently, Roe adopted the trimester framework (which essentially granted states greater power to regulate abortion as a pregnancy progressed) to guide lawmakers. (The 1992 case Planned Parenthood v. Casey dropped the trimester framework in favor of a fetal viability standard.)

Roe was a practical decision, but it was also a constitutional stretch. The Constitution makes no mention of trimesters, and their use in Roe is both mathematically convenient and legally novel. (That the Constitution not only makes no mention of “trimesters” but also “viability,” “pregnancy,” “abortion,” and “women” is an issue I’ll deal with in future articles.) Harry Blackmun, the author of Roe, not only based his opinion on a controversial reading of the Fourteenth Amendment but used a non-legal framework to structure his legal ruling. It is not hard to argue that Blackmun as a Supreme Court justice did not interpret the law but instead made it, which is what the legislative branch is supposed to do.

Consequently, because the Constitution is silent on abortion and because the issue involves conflicts over issues that are moral and scientific in nature but that moral and scientific reasoning has struggled to resolve definitively, a strong case can be made that abortion ought to be regulated not by unelected judges with lifetime appointments like Blackmun or Samuel Alito (the author of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the case that overturned Roe) but by democratically-elected legislatures. Legislatures are much more likely to reflect the will of the people, account for a wider range of views on issues, and be held accountable by the people if they [legislatures] stray from popular opinion. That’s an argument for judicial restraint.

This critique of Roe as insufficiently democratic is not new. It’s an argument liberal icon Ruth Bader Ginsburg made in 1992:

Roe v. Wade, in contrast, invited no dialogue with legislators. Instead, it seemed entirely to remove the ball from the legislators’ court. In 1973, when Roe issued, abortion law was in a state of change across the nation. As the Supreme Court itself noted, there was a marked trend in state legislatures “toward liberalization of abortion statutes.” That movement for legislative change ran parallel to another law revision effort then underway: The change from fault to no-fault divorce regimes, a reform that swept through the state legislatures and captured all of them by the mid-1980s.

No measured motion, the Roe decision left virtually no state with laws fully conforming to the Court’s delineation of abortion regulation still permissible. Around that extraordinary decision, a well-organized and vocal right-to-life movement rallied and succeeded, for a considerable time, in turning the legislative tide in the opposite direction.

That doesn’t mean Ginsburg opposed abortion rights. Quite the opposite. She supported Roe because she believed it brought about the correct outcome, but disagreed with the Court’s reasoning (she would have based the constitutional right to an abortion on the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause to shift the emphasis in the case to women’s rights rather than the generalized right to privacy derived from the Due Process Clause) and tack. Ginsburg thought a more prudent path forward would have been for the Court to simply strike down the Texas law contested in Roe v. Wade that made abortion illegal in every circumstance except to save the life of the mother. She believed states were already liberalizing their abortion laws when Roe was handed down and that a more limited ruling would have nudged the holdouts in that direction. That would have kept debates about abortion in the legislative arena, where they would have been resolved through democratic processes, as most contentious issues in the United States are. (In other western democracies, where abortion is a much less contentious issue, abortion is an issue typically regulated by national legislatures.)

Some might argue the rights Roe enshrined should be placed beyond the whims of popular opinion, but pro-life advocates would likely argue the same thing when it comes to the rights of the embryo or the fetus. In a lot of ways, then, this debate over Roe and Dobbs is essentially a debate over who should decide questions about abortion: Judges or legislators. Alito makes his view on this very clear at the end of the introduction to Dobbs:

It is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people’s elected representatives. “The permissibility of abortion, and the limitations, upon it, are to be resolved like most important questions in our democracy: by citizens trying to persuade one another and then voting.” Casey, 505 U. S., at 979 (Scalia, J., concurring in judgment in part and dissenting in part). That is what the Constitution and the rule of law demand.

Therefore, in one sense, the end of Roe corrects a long-standing critique of American democracy: That the Supreme Court for fifty years has prevented the American people from deciding for themselves how to regulate abortion. Now democracy can finally work its magic.

But American democracy is in a pretty fragile state right now. Furthermore, not only do I believe the American democratic system is increasingly outdated, in some cases, the Supreme Court as guided by its conservative majority in recent years seems inclined to roll back features that have attempted to address these shortcomings. Dobbs may return the issue of abortion to the democratic arena, but American democracy in its current state will struggle to do its demos justice.

Let’s begin with the presidency, a position filled by the candidate who wins a majority of votes in the Electoral College. That means it’s possible for the candidate who wins the most popular votes not to become president, which has happened two times in the past six elections (2000 and 2016) and nearly happened again in 2020 (switch about 5,230 votes in Arizona, 5,890 votes in Georgia, and 10,345 in Wisconsin and Trump would have won the presidency despite losing the popular vote to Biden by about 7 million votes, or about 4.4%.) Given the way voters and electoral votes are distributed among the states, the likelihood that a candidate who loses the popular vote will become president has increased significantly since 2016, with Democrats needing to win the popular vote by about 4% just to break even in the Electoral College.

It’s obviously a problem when the candidate preferred by most voters does not become president. That’s just not how democracy is supposed to work. Such a president is also more likely to pursue a policy agenda at odds with the preferences and priorities of most voters.

But the repercussions of an anti-democratic Electoral College aren’t just confined to the Executive Branch. Presidents get to nominate justices to the Supreme Court. Trump put three judges on the Supreme Court even though he lost the popular vote in 2016, giving the loser of that election an outsized influence over the ideological direction of the Court for decades to come. (Recall how Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said following the death of Justice Antonin Scalia in February 2016 that the Senate would leave Scalia’s seat open until after the 2016 election so the American people could weigh in on who should be empowered to fill that seat with their votes in the 2016 election. The voters said Hillary Clinton, not Donald Trump, yet we ended up with Justice Neil Gorsuch. McConnell’s principle somehow didn’t apply in 2020, however, following the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.) All this increases the likelihood that the Supreme Court’s decisions won’t reflect the inclinations of the American public.

The Court, of course, is not a democratic institution, and isn’t necessarily expected to follow popular opinion. It can, however, claim some democratic legitimacy through the nomination and confirmation process. It might lose some of that legitimacy and could very well find itself working against the democratic current of the country if a rump of the Court’s majority was put on the bench by the loser of the popular vote in a presidential election. It might find itself even further out of step with the country if the members of that rump were confirmed by a Senate majority that did not represent a majority of the American people. For example, when the Senate voted to confirm Trump nominee Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court in 2020, the 52 senators who voted for her represented about 13.5 million fewer people than the 48 senators who voted against her. In fact, there have only been three Supreme Court justices who were nominated by a president who lost the popular vote and confirmed by a Senate majority that represented less than half the American people. All three of those justices are currently serving on the Supreme Court (Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Barrett).

How is that possible? Because representation in the Senate isn’t apportioned by population but by state. That means the two least-populous states in the United States (Wyoming and Vermont) together amount to only 3.2% of the most-populous state’s (California) population but together have twice as many representatives in the Senate as California. Just as there is one senator per every 18.6 million Californians, there is one senator per every 0.3 million Wyomingites. Republicans currently hold a 29-21 Senate majority in the 25 least-populous states, which explains how they can hold onto exactly half the seats in the Senate yet represent 41.5 million fewer people than Democrats. (Pushed to its extreme, if the 25 least-populous states voted in a bloc against the 25 most-populous states, that 50-member bloc of small-state senators would only represent 16% of the country’s population.) If you want to look at raw vote totals, over the past three Senate cycles (when at least every seat was contested) Democratic candidates won 141.5 million votes (55.1%) compared to the 115.2 million (44.9%) won by Republicans. As all this demonstrates, the Senate by design often works against popular majorities.

So let’s imagine Democrats decide to resolve the abortion debate the way Alito wants them to: Through the legislative process. They could start by passing a bill in the House, which Democrats currently control but is so gerrymandered that Nathaniel Rakich at FiveThirtyEight estimates that if the national House vote split 50-50 in the 2022 elections that Republicans would end up winning 230 seats compared to Democrats’ 205 seats. That means Democrats would have to do a few points better than 50% simply to gain control of the House and need to win in a landslide to gain a comfortable majority.

The House is so gerrymandered because many of the state legislatures that play a big role in redistricting are themselves extremely gerrymandered. Wisconsin is an extreme example. In the 2020 State Assembly election, Republicans won 53.8% of the vote compared to 45.3% for Democrats but walked away with 61 out of 99 Assembly seats. But what’s truly remarkable about that is Republicans did way better that year than they did in 2018, when they only won 44.8% of the vote compared to 53.0% of the vote for Democrats, yet still won 63 seats in the State Assembly. Wisconsin Republicans have basically drawn themselves into a permanent majority in the Badger State, which allows them to gerrymander the state’s House seats.

Voters in Wisconsin—which is basically a 50-50 state—obviously can’t fix that problem at the ballot box. Instead, they’d have to go to court, but the Supreme Court ruled in 2019 that federal judges can’t intervene to stop partisan gerrymandering. That leaves state courts as an option, but just this week the Supreme Court announced they’ll hear a case next term about whether state courts can strike down maps drawn by state legislatures. It’s not clear yet where the Court might go with this case, but they seem to be flirting with the “independent state legislature doctrine,” an idea the Court has repeatedly shot down for most of the last century but that appears to have gained traction with the Court’s five most conservative members. As Ian Millhiser of Vox writes:

Under the strongest form of this doctrine, all state constitutional provisions that constrain state lawmakers’ ability to skew federal elections would cease to function. State courts would lose their power to strike down anti-democratic state laws, such as a gerrymander that violates the state constitution or a law that tosses out ballots for arbitrary reasons. And state governors, who ordinarily have the power to veto new state election laws, would lose that power.

As Justice Neil Gorsuch described this approach in a 2020 concurring opinion in a case concerning the deadline for casting mail-in ballots in Wisconsin, “the Constitution provides that state legislatures — not federal judges, not state judges, not state governors, not other state officials — bear primary responsibility for setting election rules.”

The independent state legislature doctrine is a scary idea because it not only could allow state legislatures to gerrymander to their hearts’ content by removing governors, the courts, and state commissions (all of which at least have the potential to make redistricting more reflective of the composition of the electorate) from the redistricting process, but it could give partisan state legislatures greater power over election administration. Some have even speculated it would empower state legislatures to throw out their state’s presidential election results and submit their own slate of electors if they so choose. It’s not clear if the Court currently has a majority willing to sign onto the independent state legislature doctrine (Barrett is the unknown) or how far they would go if they did endorse it, but it’s clear they’re seriously entertaining the idea.

(It’s also worth noting here the power state legislatures have over electoral laws, specifically voting regulations, which vary state by state. Recently, Republican-led legislatures have passed laws making it harder for people to vote [i.e., voter ID requirements, absentee ballots restrictions, closing polling sites, etc.] These attempts at voter suppression—many of which are targeted at minority communities—can produce electoral results that do not reflect the will of the people. The federal Voting Rights Act is supposed to prevent much of this from happening, but in Shelby v. Holder [2013] and Brnovich v. DNC [2021], the Supreme Court has limited the reach of that law. What’s really messed up is that a lot of Republican-led states passed voter suppression laws following the 2020 election in order to prevent a bunch of voter fraud that never really occurred in that election. In other words, the laws state legislatures have passed that have demonstrably made it harder for people to vote are premised on reasons that are almost demonstrably non-existent. [For more on this, see the Brennan Center’s “Debunking the Voter Fraud Myth” memo.])

But anyway, let’s say an abortion bill does pass the House. That wouldn’t necessarily be surprising since Democrats currently hold a (slim) majority in the People’s Chamber. That bill would likely go nowhere in the Senate, however, not because Democrats hold a majority only by virtue of Vice President Kamala Harris’ tie-breaking vote, meaning a conservative Democrat like Joe Manchin could scuttle their ambitions by voting no, but because even though Democrats have the slimmest of majorities they would still need to overcome the Senate’s filibuster, which requires at least sixty senators to end debate on a bill to advance it to a simple majority floor vote. So yes, not only is representation in the Senate allocated disproportionately, the chamber also has rules that require supermajorities in order to pass legislation (and that alternately grant minorities of at least 40 senators the power to essentially veto bills.)

But let’s say the House’s abortion bill miraculously gains the support of not 1 nor 5 nor 9 but 10 Republican senators and is sent over to a White House currently occupied by a Democratic president who signs it into law. And let’s say that bill basically codifies the framework in Casey, meaning it doesn’t go any further than what the Supreme Court endorsed in 1992. My guess is the conservative majority on the Supreme Court that just announced the debate over abortion must be returned to the people would strike that law down because while the Constitution allows the federal government to regulate matters related to interstate commerce (of which abortion would not qualify) the power to regulate the health, safety, morals, and general welfare of the people (the “police power”) is instead reserved to the states. It would therefore be up to each state to regulate abortion as they see fit.

A reasonable person may wonder how the status of a pregnant person in California (where abortion is legal) differs from the status of a pregnant person in Oklahoma (where abortion is almost entirely banned.) That may lead that person to conclude abortion regulations should not be decided on a state-by-state basis but should apply to all women in the United States regardless of whether a woman is in New York City, New York, or Jackson, Mississippi. The way around the Supreme Court, then, would be to amend the Constitution, perhaps by revisiting the powers enumerated to the federal government to allow it to regulate abortion or by asserting a constitutional right to abortion. But amending the Constitution is itself a herculean task involving state legislatures and supermajorities that is far more demanding than passing basic legislation.

Some might argue these are just the rules our democracy operates under and that since they apply equally to everyone and allow everyone to have their say, they are fair. But the measure of a democracy isn’t simply a matter of whether procedures are followed. A strong democracy is one in which the government (among other virtues) reflects the will of the people and is accountable to the people. This is not to argue the only good form of democracy is a direct democracy—democracy can certainly be refined through republican and representative systems—but rather that in a democracy, the government should not stray too far from the preferences of the public. A democratic system featuring an Electoral College, a malapportioned Senate, the filibuster, partisan gerrymandering, and a federal system that too often favors the rights and privileges of states over those of its national citizens is one that can too easily marginalize the will of the people. This is particularly true when partisans are more determined to pursue political advantage than they are with preserving a well-functioning democracy that lives up to its name.

So when Samuel Alito declares in Dobbs that the issue of abortion has been returned to the realm of democracy, the small-d democrat in me is not above admitting that yes, that’s where the finer points of this issue need to be worked out. But the small-d democrat in me also looks at the landscape of our democracy and worries it contains too many features that run counter to the spirit of democracy, which will make it that much harder for the people to ultimately guide their government’s response to this issue. Alito makes it sound like democracy can just sort of sort this all out, but that’s too rosy a picture of American democracy, particularly in its current state. Given how convoluted and quirky our democratic system is, it’s just as likely the will of the people—even one representing a solid majority of the people—will go unheeded. That’s not how democracy is supposed to work.

Signals and Noise

This is quite the headline: “Cassidy Hutchinson Held Their Manhoods Cheap” by Tim Miller for The Bulwark (“This afternoon a 26-year-old former assistant showed more courage and integrity than an entire administration full of grown-ass adults who were purportedly working in service to the American people, but had long ago decided to serve only their ambition and grievance. Cassidy Hutchinson did so at risk to her safety. Her social circle. Her career.

And she overcame all of the self-serving rationalizations that prevented the powerful, whose manhoods she held in her palm, from stepping to the plate.”)

Something worth remembering after watching Cassidy Hutchinson testify, from the New York Times: “The capital’s power centers may be helmed largely by the geriatric set, but they are fueled by recent college graduates, often with little to no previous job experience beyond an internship. And while many of those young players rank low on the official food chain, their proximity to the pinnacle of power gives them disproportionate influence, and a front-row seat to critical moments that can define the country. Sometimes, the interns themselves appear to be running the show.”

This is pretty blunt. By Heather Cox Richardson: “What emerged from today’s explosive hearing [with Cassidy Hutchinson] was the story of a president and his close advisors who planned a coup, sent an armed mob to the Capitol, approved of calls to murder the vice president, and had to be forced to call the mob off. Two of the president’s closest advisors then asked for a presidential pardon. While they did not get those pardons, Trump’s PAC later gave $1 million to Meadows’s Conservative Partnership Institute.”

As Hutchinson testified, Trump knew members of the crowd at his rally on the Ellipse were armed (“they’re not here to hurt me” he said upon demanding the Secret Service remove the metal detectors that were keeping armed rallygoers from entering the rally) yet still encouraged them to march on the Capitol. That runs directly counter to Trump’s claim the protesters were peaceful or simply got carried away. He knew they were dangerous.

From The Guardian: “The former Trump White House aide Cassidy Hutchinson received at least one message tacitly warning her not to cooperate with the House January 6 select committee from an associate of former chief of staff Mark Meadows, according to two sources familiar with the matter.”

Hutchinson testified she heard that Trump physically accosted a Secret Service agent on 1/6 when his detail refused to drive him to the Capitol. Yet Carol Leonnig, who has authored a history of the Secret Service since 1963, reports many Secret Service agents were pulling for Trump and supportive of the insurrection on 1/6, which she calls “problematic.”

Jonathan Chait calls 1/6 the “greatest political scandal in American history,” making it “all the more striking…that the Republican Party stance was, and is, that none of this should be investigated.” David Frum calls 1/6 “the worst political crime in the history of the presidency” and slams Kevin McCarthy for denouncing the riot on the day it occurred only to defend Trump ever since.

One of the lawyers who defended Trump during his first impeachment trial is pretty sure Trump can be charged with insurrection.

From video testimony by Michael Flynn testifying before the January 6 Committee:

LIZ CHENEY: Gen. Flynn, do you believe the violence on Jan. 6 was justified morally?MICHAEL FLYNN: Take the Fifth.

CHENEY: Do you believe the violence on Jan. 6 was justified legally?

FLYNN: Fifth.

CHENEY: Gen. Flynn, do you believe in the peaceful transfer of power in the United States of America?FLYNN: The Fifth.

Liz Cheney, during a speech at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library: “We are confronting a domestic threat that we have never faced before — and that is a former President who is attempting to unravel the foundations of our constitutional Republic. And he is aided by Republican leaders and elected officials who have made themselves willing hostages to this dangerous and irrational man.”

By Adam Serwer, for The Atlantic: “Don’t Forget That 43 Senate Republicans Let Trump Get Away With It” (“Although seven Republican senators broke ranks and voted to convict Trump, most of the caucus remained loyal to a man who attempted to bring down the republic, because in the end, they would have been content to rule over the ruins.”) (I would add it wasn’t as though they didn’t have a front row seat to what happened either. May they have been worried about their own exposure if they had convicted Trump?)

By David French: “Roe is Reversed, and the Right Isn’t Ready” (“[T]the Republican branch of the American church is adopting the political culture of the secular right. With a few notable exceptions, it not only didn’t resist the hatred and fury of the MAGA movement, it was the MAGA movement. And this is the culture that’s going to lead the effort to heal our nation, love the marginalized, and ask young women to face an uncertain future and endure a physical ordeal for the sake of sacrificial love?”)

By David Frum, for The Atlantic: “Roe is the New Prohibition” (OK, I get where that headline is going, but it should read “Dobbs is the New Prohibition”.)

By Aaron Blake, for the Washington Post: “The GOP’s False Assurances That Roe v. Wade Was Safe” (“The overturning of Roe v. Wade has long occupied an unusual space in conservative politics. On the one hand, the Republican Party has pushed for it for decades; on the other, even as it has done so, plenty within its ranks have assured that it wasn’t happening. The party seemed to want the benefits of the push with its base, without the consequences of the unpopular prospect with the broader electorate. It also knew that overturning Roe was a red line for some key abortion-rights-supporting GOP senators whose votes were needed to confirm the justices who would eventually overturn Roe. So it — and, crucially, those senators themselves — shrugged off the notion as if it were some kind of manufactured political issue. All of those assurances have now proved foolhardy, at best, and cynical, at worst.”)

This is ominous. From AP: “More than 1 million voters across 43 states have switched to the Republican Party over the last year, according to voter registration data analyzed by The Associated Press. The previously unreported number reflects a phenomenon that is playing out in virtually every region of the country — Democratic and Republican states along with cities and small towns — in the period since President Joe Biden replaced former President Donald Trump. But nowhere is the shift more pronounced — and dangerous for Democrats — than in the suburbs, where well-educated swing voters who turned against Trump’s Republican Party in recent years appear to be swinging back.”

But Democratic strategists seem to believe the end of Roe will be a “game changer” in the fall midterms.

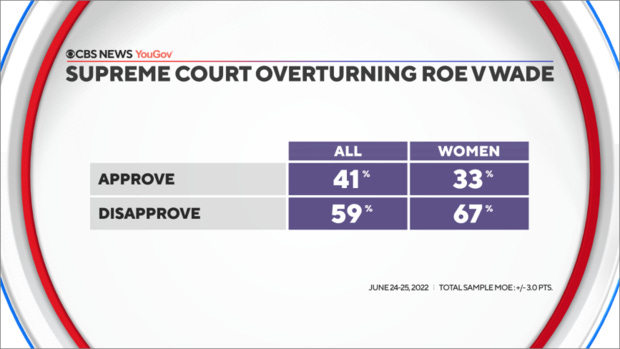

From a CBS News poll of American adults:

Anti-abortion lawmakers aren’t satisfied with returning the issue of abortion to the states. They want a federal ban on abortion, laws prohibiting people from travelling across state lines to get abortions, and legislation that would prohibit the distribution of abortion pills.

REPORTER: So that 12-year-old child molested by her father and uncle should carry that pregnancy to term?

MISSISSIPPI HOUSE SPEAKER PHILIP GUNN: That is my personal belief. I believe life begins at conception.

Democratic Virginia Rep. Abigail Spanberger’s opponent Yesli Vega thinks it’s reasonable to believe it’s harder for women to get pregnant as the result of rape.

Many are worried after ending Roe v. Wade that the conservative majority on the Supreme Court might revisit other cases that have prevented states from banning contraception, intimate same-sex relationships, and same-sex marriage. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton said he is prepared to defend the state’s anti-sodomy law if the Court moves in that direction. Ohio State Rep. Jean Schmidt has indicated a willingness to debate the merits of banning contraception.

The Supreme Court ruled this week in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District that a high school football coach had a constitutional right to pray at the 50 yard line at the conclusion of his school’s games, which, yes, he can, but in this case, the coach turned it into a spectacle involving both teams and players felt compelled to join because they didn’t want to be looked down upon by the coach. That would be a problem even by the standards of Neil Gorsuch’s majority opinion, but as Ian Millhiser writes for Vox, Gorsuch still found the coach’s actions constitutional because Gorsuch chose to misrepresent the facts in the case.

Representative Lauren Boebert (R-CO): “The church is supposed to direct the government. The government is not supposed to direct the church. That is not how our Founding Fathers intended it. I’m tired of this separation of church and state junk that’s not in the Constitution. It was in a stinking letter, and it means nothing like what they say it does.”

The neo-Nazi publisher of The Daily Stormer has “forcefully” endorsed Blake Masters in the Republican Arizona Senate primary. Polls have Masters leading the contest.

By Paul Krugman, for the New York Times: “Why Did Republicans Become So Extreme?”

In good news, Republicans in Colorado have kept election deniers from winning their party’s nomination for secretary of state. One of the election deniers who lost was Tina Peters, who has been charged with seven felonies for copying sensitive voter data. Peters, like a number of other Republicans who have lost primaries this year, has claimed the results of her race have been manipulated.

New York state is fighting back against the Supreme Court’s rulings on guns and abortion.

Mitch McConnell is threatening to derail a bipartisan semiconductor bill if Democrats resurrect the Build Back Better plan.

According to Gallup, only 34% of voters under the age of thirty approve of the job Joe Biden has done as president. Yet the number of young people who intend to vote in the 2022 midterms is roughly the same as the number who said they would at this time in 2018, and pollsters don’t expect them to drift in significant numbers toward Republican candidates.

By Heather Gillers for the Wall Street Journal: “Main Street Pensions Take Wall Street Gamble by Investing Borrowed Money” (Municipalities have assumed about $10 billion in debt this year to shore up retirement obligations) Meanwhile, the S&P 500 is on track for its worst first-half performance since 1970.

A Texas educational board has recommended describing slavery as “involuntary relocation” to second grade students in accordance with a new state law designed to ensure students do not “feel discomfort” in the classroom.

Republicans in the Michigan House have proposed fining schools $10,000 if they expose students to drag shows. There is no evidence a Michigan school has ever done that.

Since 2005, one-quarter of the United States’ local newspapers have ceased publication. That number is expected to rise to one-third by 2025.

By Ed Yong, for The Atlantic: “America is Sliding into the Long Pandemic Defeat: In the face of government inaction, the country’s best chance at keeping the crisis from spiraling relies on everyone to keep caring”

“As the Fourth of July looms with its flags and its barbecues and its full-throated patriotism, I find myself mulling over the idea of American exceptionalism. What, if anything, makes this country different from other countries, or from the rest of the developed world, in terms of morals or ideals? In what ways do our distinct values inform how America treats its own citizens? I land on a distinct absence of mercy.”—Pamela Paul, from “America the Merciless,” for the New York Times

Vincent’s Picks: The Bear

If it’s not one thing, it’s another at the Original Beef of Chicagoland, the restaurant that serves as the setting for The Bear, an eight episode FX dramedy now streaming on Hulu: The supplier hasn’t delivered enough meat, there aren’t enough napkins, the knives aren’t sharp enough, the kitchen staff is stubborn and resentful, the bread is too crumbly, the pop machine is broken, the ice cream machine is busted (although nobody knew they served ice cream), the toilet is backed up, work stations are filthy, there’s a feisty mob of gamers outside, the electricity is out, the place is way short on money, and everyone is yelling at each other. But does it really need to be this way? It’s just a sandwich shop. Why so edgy? Why so intense? The beef they’re serving up here is more than just meat.

Jeremy Allen White (Shameless) stars as Carmen “Carmy” Berzatto, a world-class chef who returns to his hometown of Chicago to salvage his family’s sandwich shop following his brother Mikey’s suicide. His sister Sugar (Abby Elliott) would just as soon sell the money pit, but Carmy is hellbent on turning the place around. He strives to make the restaurant’s offerings higher quality and more appetizing, and tries to bring some much-needed order and efficiency to the kitchen. To this end he hires Sydney, played by Ayo Edebiri (Big Mouth, Dickinson), as sous-chef.

The staff (including Liza Colón-Zayas as Tina and Lionel Boyce as Marcus) is for the most part skeptical of these outsiders’ attempts to polish this greasy spoon. The most resistant employee is Richie, played by Ebon Moss-Bachrach (Girls, The Punisher), a family friend Carmy calls “cousin.” Richie insists Carmy’s new “system” and menu changes are ill-suited to the restaurant’s neighborhood and clientele, and he makes these views as loud and clear and coarse as possible. Any time Richie sets foot in the shop, the mood goes from extremely tense to explosive. Carmy attempts to counter Richie’s crassness with respect (he refers to everyone in the kitchen as “chef”) but his intensity, ambition, and high standards grate on the staff.

Christopher Storer and Joanna Calo, The Bear’s showrunners, bring a Robert Altman vibe to the show. Dialogue, sometimes coming from off-camera, is piled on top of itself. Jokes and quips are often mumbled and pushed to the background. The camera occasionally has to catch up to the main action. The show also has a gritty, 1970s feel to it, particularly when it focuses on people laboring in the grimy kitchen or traversing the streets of Chicago. In particular, White as Carmy looks like he could have wandered in from a late-70s Scorsese flick. There’s nothing glamorous here.

All this helps to emphasize just how marooned in time the Beef is. The restaurant is decorated in film posters from the late 80s and early 90s, and a sign on the wall informs customers the place hasn’t really changed since 1987. The Beef feels like an artifact of Peak Chicago, the great middle American metropolis, the setting of so many John Hughes films and the home of Da Bears and Michael Jordan. Yet this isn’t 1987 anymore, and to survive, the Beef will need to change, or at least update itself. Hence the beef at the heart of the Beef.

We can appreciate where each of these characters is coming from. Richie and much of the staff would be out of their league in a revamped kitchen, yet they have to admit Carmy’s system is superior to Mikey’s and his food tastes way better as well. Carmy, with Sydney’s help, makes the Beef a better restaurant, one that actually makes money, believes its regulars deserve more than slop, and that can take pride in its well-prepared culinary offerings. But it’s also fair to wonder why trained chefs like Carmy and Sydney are trying to overhaul a sandwich shop serving beef subs and Chicago dogs to its neighborhood clientele. It’s definitely personal for Carmy, but he’s also not presiding over a Michelin-level kitchen and no one’s expecting him to craft the world’s greatest meat sandwich. There has to be a way to work with what the Beef already is.

White and Moss-Bachrach are outstanding as The Bear’s main antagonists, but Edebiri’s Sydney is the heart of the show. Sydney takes the job as sous-chef not only to work with an elite chef like Carmy (she’s a graduate of the Culinary Institute of America herself) but because the Beef was one of her father’s favorite places to eat. Sydney’s gone into massive debt to become a first-rate chef, has toiled zesting lemons in elite kitchens, and failed trying to start her own restaurant. A sweet and decent person and a true culinary artist, she deserves a break. Edebiri captures how wearied Sydney feels in a world where her talent should command more respect, where her personal economic prospects should be better, and where she shouldn’t have to put up with the absurdity that surrounds and at times suffocates her. As the Beef’s more-than-able second-in-command, Sydney takes heat from both the employees and her boss, but Edebiri wisely finds other ways to joust with those who roast her beyond spitting fire back at them (although she’s more than capable of holding her own with Richie.) If the Beef ever gets its act together, it will probably be Sydney who puts them back on track.

The Bear is at its best when everything’s boiling over in the kitchen. After three episodes, it slows down a bit, which some in the audience may appreciate, but I preferred the high tension as a viewer, as it seemed more true to its time. (If you’re worried this show may be too intense for you, know the episodes are only about half an hour long.) Was the Original Beef of Chicagoland always this dysfunctional? Can it change? Should it change? Is it worth changing? What is it even aspiring to be? They’re issues worth discussing, but no one has the time, not with all this food that needs to be prepped and the lunch hour rush looming and a boat-load of debt that needs to be paid off. Whatever answers they find will be negotiated in the moment with a whole lot of screaming. Such is life at the Beef.

Exit Music: “Only a Memory” by the Smithereens (1988, Green Thoughts)

I use the phrase “pregnant person” to implicate men in the abortion debate. It’s often too easy for men to see references to “women” or “mothers” in discussions of abortion and then check out or deprioritize the issue since something that happens only to women or mothers is not something they as men will experience or need to worry about. By using the phrase “pregnant person,” my aim is to encourage men to approach the issue of abortion as one relevant to the human condition generally.