Trump is Breaking the Constitution. We May Not Be Able to Put It Back Together Again.

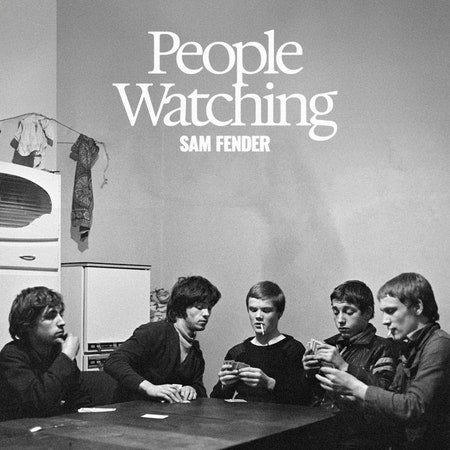

PLUS: A review of "People Watching" by Sam Fender

“But the great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department, consists in giving to those who administer each department, the necessary constitutional means, and personal motives, to resist encroachments of the others. … Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. … It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to controul the abuses of government. But what is government itself but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controuls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: You must first enable the government to controul the governed; and in the next place, oblige it to controul itself.”

—James Madison, Federalist No. 51, 1788

“A republic, if you can keep it.”

—Benjamin Franklin, on the last day of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, responding to Elizabeth Willing Powel’s question as to what form of government—a republic or a monarchy—the delegates had designed for the nation.

“Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall.

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men

Couldn’t put Humpty together again.”

—English nursery rhyme

It has long been a matter of faith among Americans that the United States Constitution could withstand the machinations of bad actors. This is the theory Federalist 51—James Madison’s explication of the separation of powers—advances. Madison concedes men are not angelic in nature. We ought not assume good people will lead the state. He admits we should be concerned about the concentration of power. But Madison argues in Federalist 51 that the Constitution by design controls for all that. The Constitution separates power, so that official political power is not concentrated in any one place. It then grants those different foci of power the means and sufficient strength to “check” and “balance” one another, which will come in useful if political actors begin to abuse their power. Finally, by embedding this system within a competitive, geographically extensive republic containing a variety of often conflicting interests, the Constitution incentivizes those with power to keep one another in line.

Again, this is all achieved by design. It reveals the faith Madison and the Founding Fathers placed in statecraft, or the idea that the basis for good government is good institutional design. Assuming the government is well-designed, the advantage of living in a nation with sound statecraft is that the state is not dependent on the goodness of its citizens or leaders, although good citizenship and good leadership certainly helps. Given the resilience of its institutions, a well-designed government should be able to withstand the meddling of un-angelic, devilish men. Some would even argue that if the statecraft is good enough, you can fill the state with devilish men and still generate good results. It’s sort of like how Madison’s contemporary Adam Smith argued the pursuit of economic self-interest in the free market could improve society as a whole.

The opposite of statecraft is soulcraft, or the notion that the basis for good government is good people, specifically good leaders. The idea is that the state will only thrive when the right people are in charge. It helps, too, when the realm is filled with good subjects who are loyal and know their proper place in the social order. To build a good state, therefore, it is necessary to instill the proper virtues in a state’s citizenry and elevate the most virtuous to positions of leadership. Emphasizing soulcraft is generally considered a more ancient way of thinking about politics while emphasizing statecraft is a more modern approach.

As nascent democrats, you can imagine why the Founding Fathers would be interested in switching the focus of their political science from soulcraft to statecraft. Soulcraft was too elitist and impractical for a nation that dreamed of settling a continent, while statecraft could help ensure that the democratic masses didn’t run roughshod over their government. But that didn’t mean the Founding Fathers thought soulcraft was unimportant. While statecraft could go a long way toward protecting the state from a dishonorable leader, the Founding Fathers believed it was absolutely critical for leaders to possess republican virtues so those leaders would be inclined to govern in the public interest. It was important citizens develop republican virtues as well, since they would be responsible for governing themselves and electing their leaders. In that way, the government would only be as virtuous as its citizenry.

It is interesting, therefore, to compare James Madison’s defense of the Constitution in Federalist 51 with Benjamin Franklin’s remarks at the conclusion of the Constitutional Convention. Madison is selling his audience on the merits of the Constitution’s statecraft. He is insisting this new national government would be foolproof and devilproof thanks to its system of separated powers. It could withstand bad actors because its design is good. But Franklin—perhaps before his signature on the Constitution was even dry—essentially told a fellow Philadelphian that the future of the new republic he had just helped create was now in their hands. Its ultimate success was not guaranteed by its design but depended instead on whether or not its citizens would take care of it and use it responsibly. It would depend on whether or not the nation’s citizens had well-crafted souls.

If you were to ask me what mattered more—statecraft or soulcraft—to the success of a state, I would argue statecraft. I don’t think we should assume the best among us will always rise into leadership positions or be immune to the corrupting influence of power if they did. A well-designed state can go a long way toward containing bad actors. That’s not to say I don’t discount soulcraft. A state works best when operated by virtuous people, but a well-designed state stands a good chance of carrying on even in their absence.

As I mentioned earlier, Americans have always put their faith in their government’s statecraft. We trust that our 236-year-old Constitution—the oldest in the world—will see us through trying times. It is actually rather amazing our constitutional system has lasted this long, given its flaws and the poor track record of democracies who have based their constitutions on our own.1 Yet for whatever reason (i.e., the diversion of political conflict to matters of federalism, a two-party system that has historically featured ideologically incoherent parties, the virtues and soulcraft of its leadership class, etc.,) survive it has. The separation of powers—the foundation of our constitutional order—has rarely been tested, and when it has, it has rarely been placed under serious strain.

Until now.

Since returning to the White House seven weeks ago, Don Trump has made it his mission to expand the power of the president beyond its constitutional limits. For example:

Trump defied Congress’s power of the purse by freezing congressionally-authorized foreign aid and numerous grants and loans. This act, called impoundment, was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in the 1970s.

Trump gutted or ended the work of congressionally-authorized agencies like the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). He has threatened to do the same to the cabinet-level Department of Education while severely hobbling the work of agencies like the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Trump used an executive order to claim greater power over independent agencies that Congress by design insulated from political pressure.

Trump arbitrarily fired swaths of government officials in violation of congressional civil service protections designed to ensure government employees are hired or fired based on merit rather than political favor. He has also fired numerous inspectors general—the individuals in agencies tasked with making sure their agency operates in accordance with the law—in defiance of laws recently enacted by Congress that protect their positions.

The officials tasked with carrying out Trump’s mission—Elon Musk’s DOGE team—operate without transparency and are asserting powers they do not legally possess.

Trump has attempted to end birthright citizenship—a provision of the 14th Amendment—via executive order.

It should be mentioned Trump is not the first president who has been accused of stretching the powers of the office. Joe Biden (student loan forgiveness), Barack Obama (DACA, military intervention in Libya), and George W. Bush (various actions related to the war on terrorism) have faced similar criticism, as have Woodrow Wilson (the Red Scare), Franklin Roosevelt (Japanese internment), and Richard Nixon (impoundment). Critics have long lamented the rise of an “imperial presidency.” (For further reading, see Julia Azari’s “Why Doesn’t Somebody Stop This?” for Good Politics/Bad Politics)

But what we are witnessing today is not part of the ordinary push-and-pull between the branches of government. Nor is it occurring in the midst of a national emergency. Instead, it’s an attempt by Trump to consolidate the powers of the federal government within the executive branch; more specifically, because I doubt Trump thinks Democratic presidents ought to have these powers, I’d argue he wants these powers to himself. He’s destroying the separation of powers in an attempt to personally monopolize power.

Trump has made his desire to wield power without restraint clear as day. In 2019, he declared, “I have an Article 2, where I have the right to do whatever I want as President.” (That’s not true; still, his lawyers argued and a conservative Supreme Court agreed that presidents can commit crimes and get away with it while in office.) Trump recently called himself a “king” on X. Vice president JD Vance stated last month that, “Judges aren’t allowed to control the executive’s legitimate power,” hinting that the Trump administration might ignore adverse judicial rulings. We should never forget that Trump already holds the democratic process and the legislative branch in contempt, as he attempted on January 6, 2021, to overturn the will of the people by siccing a violent mob—the members of which he pardoned within hours of taking office, essentially absolving himself of wrongdoing—on Congress. That suggests we should take Trump’s desire to serve a third term as president seriously.

Trump’s lust for power is reflected in his approach to governance, which Jonathan Rauch has identified as patrimonialism. Rauch defines patrimonialism as “replacing impersonal, formal lines of authority with personalized, informal ones.” Under a patrimonial regime, the state’s authority is not checked by rule-bound institutions; instead, it is wielded according to the whims of the leader. To this end, Trump needs cronies in charge of state agencies who will enact his agenda even if it conflicts with the law or their better judgment; similarly, he needs dispassionate, duty-bound bureaucrats and ethics watchdogs out of the picture so they don’t resist his imperatives or call out his poor governance or corruption. Trump has also created shady channels for individuals to curry favor and prove their loyalty to him. His meme coin allows people interested in doing business with his government to pad his wealth. At the same time, he has made it known he will fire, humiliate, or punish those who are insufficiently loyal to him. (Jamelle Bouie of the New York Times recently argued one of Trump’s targets for retribution is the American public itself.) Trump does not see himself as someone operating within a system in which power is shared by multiple players but as someone who lords his power over others.

This is an unprecedented political confrontation over the separation of powers. Congress may eventually conclude it needs to reassert its powers as a coequal branch of government by passing laws that exert greater control over the operations of the federal government. Mustering the necessary level of support needed to do that in a mostly gridlocked Congress full of sycophantic Republicans could prove extremely difficult, however. In that case, it would fall to the courts and ultimately the Supreme Court to rein in Trump. It’s possible John Roberts and Amy Coney Barrett—the most Trump-skeptical conservative justices on the Court—would join the three liberal justices to restore balance to our system of separated powers. Yet no one would be surprised if the Court’s conservative bloc rolled over for King Donald, either.

And then, of course, there’s the question of whether Trump would even abide by the terms of a newly-passed law or respect a Supreme Court decision that concluded he had overstepped his authority. If he didn’t, our country would find itself in an unprecedented constitutional crisis. (For more on this prospect, see “The One Question That Really Matters: If Trump Defies the Courts, Then What?” by Erwin Chemerinsky for the New York Times.)

But here’s the rub: Even if a Republican Congress got up on its hind legs to defy Trump; or even if Democrats won a landslide victory in the 2026 midterms and gained veto-proof majorities in the House and Senate and passed legislation to curb Trump; or even if the Supreme Court ruled against Trump; and even if Trump accepted all that and stood down: Even under those best-case scenarios, the problem is the autocratic cat is out of the constitutional bag. Our vaunted statecraft has been exposed. Trump II learned an important lesson from Trump I. The lesson Trump II learned was not that Trump I went too far. Instead, the lesson Trump II learned was that Trump I did not push the system hard enough. The system was more fragile than people assumed. It was not necessary for a president to possess extraordinary political skill to realize his political goals. All it took was a president with enough willpower to break the system. And even if Trump II fails or relents, there is a Trump III out there whose main takeaway from all this is that when he takes the throne, he’ll need to push even harder.

Compounding the problem is the speed and recklessness of Trump’s actions. Perhaps Trump is trying to overwhelm the system and shock his opponents into submission. It could be he’s just trying to affect as much change as quickly as possible. Or maybe his goal is to break as much as he can before someone orders him to stop so that the damage is irreversible. Regardless, what we have is a rogue president waging an insurrection against the government from within the executive branch. Within a matter of weeks, he has completely upended the nation’s foreign policy. His shoot-from-the-hip economic agenda could boost inflation, tip the country into a recession, or both. Musk’s interventions have ended programs that affect the livelihoods of millions of people and may be impossible to restart. Musk has even gone from rooting out “waste and fraud” in Social Security to questioning the legitimacy of the program itself. Who knows what other damage Trump could do unilaterally. The danger here isn’t just that an unchained president could upend our system of separated powers, but that a president drunk on a strongman’s conception of executive power may without forbearance wreck the government’s capacity to provide for the well-being of its citizens, violate basic tenets of the social contract, or trample upon the nation’s core values. It’s a terrible lesson for future presidents to learn: If you want to do something unconstitutional, just do it so quickly that by the time you’re told to stop, the damage you’ve wrought is permanent.

I’m worried Trump is breaking the Constitution and that we’ve reached the point where even if he is stopped and the damage is somehow contained, we will no longer be able to rely on the Constitution as a stable basis for our democracy. Trump has exposed its flaws. Whenever and however the Trump era ends, I don’t think we should assume we will simply return to an era of constitutional politics as usual. Bad actors will be looking to exploit the system’s known weaknesses.

This country will need a new round of statecraft post-Trump. I don’t know if that will require simply amending the Constitution or drafting a completely new founding document, but we need politically-minded people discussing these issues now. In fact, a movement aimed at revitalizing democracy may be the sort of positive project that can propel the country into a post-Trump era. While I know much has been made over the past few months about how “democracy” was not a salient issue with voters in the 2024 election, the notion of a “democratic revival” may pack more of a punch if it wasn’t focused solely on statecraft but also on issues connected to soulcraft (like ethics in government) and policies related to what many would consider basic rights (like healthcare.) Again, I don’t know what this would all entail, but I feel it is a big subject I need to write more about.

My hopeful conclusion is that a new and better statecraft may emerge from the eventual wreckage of Trumpism. But I must also admit the importance of soulcraft has been nagging at me as I’ve written this essay. I’ve argued the statecraft of our Constitution is flawed and that we have perhaps placed too much faith in its design. But what if my modern mind has placed too much faith in the possibilities of statecraft? Can statecraft really succeed if established on a foundation of poor soulcraft? Aren’t all forms of government vulnerable to the machinations of bad men? I don’t think that’s a reason to forego attempts to improve our statecraft. I worry, however, if there are currently enough virtuous souls in this country to not only empower a democratic renaissance, but to keep it.

Signals and Noise

“The Adolescent Style in American Politics” by Jill Filipovic (The Atlantic)

“When You’re MAGA, They Let You Do It” by Helen Lewis (The Atlantic)

“Here’s the Real Threat to ‘Personal Liberties and Free Markets’” by Dana Milbank (Washington Post)

“What the Numbers Say About the Erosion of American Freedom” by Philip Bump (Washington Post)

“I’m a Rust Belt Democrat From a Swing District. Anti-Tariff Absolutism Is a Mistake” by Rep. Chris Deluzio (New York Times)

“The Real Goal of the Trump Economy” by Jonathan Chait (The Atlantic)

“Elon Musk’s Business Empire is Built on $38 Billion in Government Funding” (Washington Post)

“Cuts For Thee, But Not For Me: Republicans Beg for DOGE Exemptions” by Catherine Rampell (Washington Post)

“‘People are Really Bulled Up’: Stock Surge Has Some on Wall Street Worried” by Declan Harty (Politico)

“What’s the Matter with Billionaires?” by Adam Bonica (On Data and Democracy)

“In First Month, Trump Upends Century-Old Approach to the World” by Michael Birnbaum (Washington Post)

“Trump Sided With Putin. What Should Europe Do Now?” by Phillips Payson O’Brien (The Atlantic)

“A Man Who Actually Stands Up to Trump” by Franklin Foer (The Atlantic)

“The Real Reason Trump Berated Zelensky” by Jonathan Chait (The Atlantic)

“At Least Now We Know the Truth” by David Frum (The Atlantic)

“It Was an Ambush” by Tom Nichols (The Atlantic)

“A Thousand Snipers in the Sky: The New War in Ukraine” (New York Times)

“The Great Resegregation” by Adam Serwer (The Atlantic)

“The Age of Anti-Woke Overreach” by Jerusalem Demsas (The Atlantic)

“Democrats Are About to Eat Their Own” (The Bulwark)

“The American Weather Forecast Is in Trouble” by Zoë Schlanger (The Atlantic)

Top Five Records Music Review: “People Watching” by Sam Fender

There is an ever-present tension in Bruce Springsteen’s music between the glorification of the individual’s pursuit of the American Dream and the price the individual frequently pays for that pursuit. Springsteen’s characters, born as they are to run, hop into cars and tear out of town to find a better life somewhere down the highway; more often than not, they wind up in a car wreck, wounded, rootless, or sneaking back into town after learning the hard way that their prospects are no better out there on the road than within the city limits. Casual Springsteen fans tend to get carried away by the exhilaration of the music while overlooking the tragedy of it all. They don’t realize Springsteen is memorializing those betrayed by the American Dream.

Sam Fender, an up-and-coming singer-songwriter from northern England, clearly counts Springsteen as an inspiration. Like Springsteen, Fender’s lyrics chronicle the lives and dashed hopes of the common people. His musical arrangements pack an E Street wallop (by way of the Killers) that turn his tales of working-class grief into epic tributes. But while you’ll hear echoes of Springsteen in Fender’s latest album People Watching, it’s not a throwback. In fact, the modern-day tension at the heart of Fender’s new record is a dilemma Springsteen—an artist whose mid-life renaissance ran out of steam following the rise of Trump—has struggled to address: What is a working-class artist to do when he finds his working-class audience drifting away from him?

Let’s not mistake Fender for someone whose success in life has severed his connection to the working-class. While he confesses on “Crumbling Empire” that he may not “wear the shoes I used to walk in”, Fender is still fully sympathetic to the plight of the working-class and angered by how nearly half a century of UK governance founded on the assumptions of Thatcherism has hollowed out British society. On the album’s opening title track, he finds himself inspired by the sight of “Everybody on the trеadmill, runnin’/ Under the billboards, out of the heat”, grinding their way through a day of work. But he’s grown jaded, as he’s coming home to visit a family friend spending her final days in a care home that is “fallin’ to bits/ Understaffed and overruled by callous hands”. It’s a critique of the government’s stewardship of the National Health Service (NHS), the UK’s comprehensive, universal, and free public healthcare system. The program is a point of national pride in the UK, but faced with staffing shortages, funding pressures, and crumbling buildings, it is currently under severe strain. That feels like a betrayal to the country’s working class, who consider the NHS a cornerstone of the nation’s social contract. Neglecting the NHS is tantamount to neglecting the working class.

On “Crumbling Empire”, which links the economic devastation he finds in the United States to that in the United Kingdom, Fender recounts the hardships his own working-class family—who more than earned their keep—has faced:

My mother delivered most the kids in this town

My step-dad drove in a tank for the crown

They left them homeless, down and out

In their crumbling empire

Later on the album, during the seething “TV Dinner”, Fender sings about being exploited by the music industry in a way anyone who has ever found themselves at the mercy of an employer can relate to. When he sings, “Fetishise their struggling while all the while, they’re suffering”, Fender isn’t simply railing against music industry executives who get rich off the work of starving artists but also calling out public figures who pay lip service to the working class while doing nothing to improve their lot in life.

Yet while Fender is heartbroken for those who have been chewed up by the long legacy of Thatcherism, he is also skeptical that the post-industrial town he grew up in offers a way forward. He begins “Rein Me In”, a jaunty song ostensibly about a failed relationship, by declaring, “I let go of everything I ever had/ ‘Cause I couldn’t give the love you deserved”. While he could be blaming himself for the break-up, Fender might also be singing about his town, where the bars are filled with his “ghosts and carcasses”, and the realization it offers him no future. “All my memories of you ring like tinnitus,” he sings, “If I stop, it’s just pain/ Please don’t rein me in”. It makes him feel guilty to admit that, but he doesn’t want to remain constrained by his hometown.

Earlier on “Wild Long Lie”, a song about running into all his old friends over the holidays (“It’s that time of the year again when your past comes home/ And everyone I’ve ever known wants it large”) he confesses, “I think I need to leave this town/ Before I go down”. It’s a tug of war for him—“I’ve got so much pain here, yet so much love” he sings, knowing if he left he’d be leaving so many he cares about behind—but his town is a dead end.

Fender’s desire to leave, however, isn’t mere opportunism. Instead, he feels the town is backward-looking, erroneously pinning its hopes on a restoration. For Fender, the cure for whatever ails the town will not be found in a past that perhaps wasn’t as rosy as it seems. Recall that in “Rein Me In”, his memories are painful like tinnitus, that ringing sound that stays in your ears long after being exposed to loud noises. Fender concludes he wants to “leave this town” when his past returns in “Wild Long Lie”. He names the problem explicitly in “Nostalgia’s Lie”. Remembering the glory days, he sings, “Those were the times where we all had nothing”. It leads Fender to question whether the past was “ever what I thought it truly was” and to reorient himself by “becom[ing] what I’ve been asking/ [and] accept[ing] the path that lays before my eyes.” The way forward isn’t backward. He knows what many in his town perhaps refuse to accept: If we long for a brighter future, we need to embrace change.

Listening to the opening of “Nostalgia’s Lie”, you’ll hear the echoes of “The Waiting” (1981) by Tom Petty and Heartbreakers. It’s a clever callback to a song that inverts the structure of the typical pop song, as Petty’s verses are about the euphoria of being with the one you love while the chorus is about the build-up to that moment. It places waiting—passivity—at the center of the action, where it really shouldn’t be. Fender seems to want to draw attention to that as a problem. His town is waiting for the return of a mythical past rather than actively dreaming about a better tomorrow. So long as that’s his town’s mentality, it won’t find the solution it needs.

It makes sense Fender would evoke Tom Petty on People Watching. Like Bruce Springsteen, Petty is a heartland rocker, and Fender clearly feels a kinship with those kinds of artists. Many of the songs on People Watching feel like they’re spun-off from the second side of Born in the U.S.A., which includes “Glory Days” and “My Hometown”. But it’s not just that Fender and Springsteen share lyrical themes. Fender also enlisted Adam Granduciel of the War on Drugs—a band famous for shrouding their music in the synthesized haze of the 1980s—to produce People Watching and imbue it with a Springsteenian grandeur. (Due to its reliance on synthesizers, drum machines, and sax solos, People Watching treats “Dancing in the Dark” as an ur-text.) It’s a risky move, as a stray synth line occasionally whisks the listener away to the days of Thatcher and Reagan. This isn’t supposed to be a nostalgic album. What Fender hopes instead is to steal some of Springsteen’s uplift and power. People Watching isn’t a quiet album; like Springsteen’s greatest anthems, it’s meant to pick-up and fortify its listeners, to give them the strength they need to carry on through the days ahead.

Like Springsteen, one can also hear Fender’s left-leaning politics straining against an ascendent right-wing populism. Some might accuse Fender of being a traitor to his class for daring to critique the provincialism of his hometown. Unlike the 75-year-old Springsteen, however, the 30-year-old Fender remains unburdened by history and legacy. He is not the steward of a tradition but an architect of the future, someone who is less interested in defending a way of life than in finding a new way forward. More importantly, Fender is telling us that while the past may slip away, it’s the people we should keep close to our hearts, a sentiment he delivers at the end of the album during the gorgeous “Remember My Name”:

That’s how Fender earns his working-class credibility: Rather than longing to restore some old mythical order, Fender believes our energy would be better spent dignifying the lives of those we share our times with. It’s a humanist perspective we desperately need today.

Exit Music: “Personality Crisis” by the New York Dolls (1973, New York Dolls) R.I.P. David Johansen

Scholar Juan Linz observed in an influential 1990 article titled “The Perils of Presidentialism” that governments in nations who modeled their constitutions on the United States’ have tended to collapse. Chile’s lasted the longest (over 150 years) but even it fell apart in the 1970s. While there are all kinds of reasons why democracies backslide and fail, Linz argued U.S.-style democracies are perhaps set up to fail because of their separation of powers. Unlike parliamentary systems, where nearly all official power flows through legislative majorities and executive power is derived from those majorities, power in U.S.-style presidential systems is divided between democratically-elected branches that can each legitimately claim to speak for the people. When conflict arises between the branches, gridlock sets in. In the worst-case scenarios, that showdown is resolved not through an election but when one of the branches, claiming to be the true voice of the people, declares the other illegitimate and somehow—perhaps via legal decree, police action, or military action—renders the other branch powerless. That effectively terminates the prevailing constitutional order. This demonstrable weakness in American statecraft is why even Germany, Japan, and Iraq have parliamentary rather than presidential systems, as it turns out that when it came time to nation-build, we did not have enough faith in our own model of democracy to recommend it to those we conquered. For more, see “American Democracy is Doomed” by Matthew Yglesias of Vox.