Make Government Work Again: Ezra Klein & Derek Thompson's "Abundance" and Marc J. Dunkelman's "Why Nothing Works"

PLUS: An NBA postseason preview

The Paul S. Sarbanes Transit Center is a 34-bay bus station in downtown Silver Spring, Maryland, just a few blocks from our home. When we first moved to the DMV in the fall of 2010, work had barely started on the bus station even though the Montgomery County Council had approved its construction (Price tag: $91 million) nearly two years earlier. Upon completion in March 2013, inspectors found multiple problems with the station, including serious design and construction defects, inadequate rebar, and weak concrete. Local officials hired the firm that rebuilt the Pentagon after 9/11 to make repairs. The station finally opened to the public in September 2015, four years overdue and $50 million overbudget.

Every time I passed the construction site on my way to catch the bus to the University of Maryland, I thought to myself, “That right there is the reason people are Republicans.” The transit station is a three-story, open-air concrete structure. I don’t want to suggest something like that is easy to build, but I wager it’s easier than the high-rise apartment in the picture below with the “Now Leasing” sign hanging from its side. That apartment building was built in a fraction of the time it took to start and finish construction on the bus station, rapidly rising into the sky while the transit hub just sat there, if not unfinished then inadequately finished, a daily reminder of the ineptitude and wastefulness of government. With that in the heart of your downtown, why would a voter want to support a liberal politician calling on the government to do more?

Regardless, voters in Montgomery County, Maryland—perched immediately north of Washington DC and packed with federal workers devoted to making government work for the people—remain committed to the Democratic Party. Many would likely blame Republicans for neglecting public problems and turning voters off to government action. It was Ronald Reagan, the patron saint of the modern GOP, who famously declared in 1981 that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” Democrats have been playing defense ever since, struggling to convince voters that government can be a force for good in their lives. In my last article of 2024, I wrote this is the mental construct Democrats need to change if they hope to become more than just the party the nation turns to when the GOP screws up.

But Montgomery County is run by Democrats. Its county executive is a Democrat, and has been since 1978. Not only does the eleven-member county council consist entirely of Democrats, but only three Republicans have served on the council since 1978, with the last one leaving the council at the end of 2006. If there’s a problem with governance in Montgomery County, it’s a Democratic problem.

Like Montgomery County, most of the nation’s largest cities—New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, San Francisco, etc.—are led by Democrats. Some of those cities are embedded in solidly blue states like California, New York, and Illinois. Yet few would consider these jurisdictions paragons of good governance. Some of that is based on dated stereotypes that view cities as lawless, corrupt, polluted, and impoverished. (Such stereotypes often overlook how prevalent those problems are in rural areas.) But there is also some truth to the observation that some of the most liberal, pro-government jurisdictions in the country struggle mightily to address the public problems they claim they want to fix.

Just consider California, where zoning laws make it extremely difficult to build new housing. Both Los Angeles and San Francisco have severe housing shortages, which prices many middle- and low-income residents—the very people progressive policies are supposed to benefit—out of the market. As the cost of living rises, many Californians have moved to Arizona and Texas, where housing is more plentiful and affordable. California also harbored grand ambitions to build a high-speed rail system, a green, fast, and affordable form of mass transit found throughout Europe and East Asia. Governor Jerry Brown and President Barack Obama threw their clout and billions of dollars into the project. Yet a long hoped-for bullet-train track connecting the population centers of San Francisco and Los Angeles has been scaled back to a line running through the Central Valley. The project, bogged down by regulations and lawsuits, has become too onerous and expensive to complete.

A new school of progressive thinkers has emerged over the past decade to argue progressives have become their own worst enemy by erecting institutional roadblocks that prevent them from using government to enact their policy agenda. California serves as a checkmate example for their argument, as Republicans in the Golden State lack the political authority to thwart Democrats, and the state is as liberal as the European nations that build public projects more efficiently and inexpensively. What that implies is there is something wrong with American-style progressivism that keeps it from realizing its goals. Two new books by progressive authors released in the past month—Why Nothing Works by Marc J. Dunkelman and Abundance by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson—aim to explain what that is.

Dunkelman, a fellow at Brown University’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, was inspired to write Why Nothing Works after re-reading The Power Broker, Robert Caro’s biography of New York City urban planner Robert Moses, during his commutes into Manhattan’s Penn Station. Moses, a singularly powerful figure in the history of New York, treated mid-century NYC the way a sculptor handles a mound of clay. He remains a controversial figure, responsible for much of the city’s modern infrastructure but also reviled for destroying neighborhoods to realize his vision. The public began to turn on him in the early 1960s when the development craze he cultivated resulted in the demolition of the original Penn Station, an architectural landmark beloved by New Yorkers. The old station was replaced by a new Penn Station located beneath Madison Square Garden. Even though it is the busiest transportation hub in the Western Hemisphere, it is reviled as a dingy, overcrowded facility. The experience left Dunkelman wondering why Moses (for good or bad) was able to accomplish so much while politicians today can do so little to fix legitimate public problems.

Dunkelman’s main argument is that progressives have gone too far in embracing their Jeffersonian character at the expense of their Hamiltonian ethos. Within the progressive tradition, a Hamiltonian (as in Alexander) will seek to solve public problems by pulling power up to a central authority. The idea here is that a central authority can bring order to an otherwise chaotic public, supply a plan that covers multiple jurisdictions, lend expertise that local authorities lack, and marshal enough political might to confront large-scale problems and powerful interests. America turned to Hamiltonian-style politics to break up corporate monopolies, regulate the banking industry, electrify the Tennessee Valley, build the interstate highway system, and put a man on the moon. Alternately, the Jeffersonian approach (named after you-know-who) aims to thwart centralized authority by pushing power down to local officials and individuals. The idea here is that small communities and individuals in a democracy ought to be empowered to defend themselves against an intrusive government as well as make decisions on their own, since they know their local or personal circumstances best.

Dunkelman argues mid-century progressives—most notably those who enacted the New Deal—were Hamiltonians who got a lot done. During the 1960s, however, progressives began to morph into anti-authoritarian Jeffersonians. This happened for a number of reasons: Some high profile instances of overreach; fear of creeping Nazi- or Soviet-style totalitarianism; a concern that industries had captured the government agencies tasked with regulating them; the rights revolution and a resurgent spirit of individualism; the disastrous war in Vietnam, which had been championed by the nation’s “best and brightest” public servants; and the Watergate scandal, which signaled public corruption and abuses of power reached the highest levels of government. By the 1980s, most Americans supported conservative calls for a less active government, but progressives also endorsed this anti-government outlook by packing legislation full of regulations individuals could use to challenge government actions in court. Many of these regulations, which were intended, among other things, to combat racial bias, protect the environment, ensure the safety of workers and citizens, and provide legal recourse to those affected by government actions, were well-intended, yet they also drove up costs and empowered individuals to delay (or even kill) projects. Progressives essentially became more concerned with process rather than results, and with protecting individual rights rather than pursuing the broader public good.

The first half of Dunkelman’s book is a history of the 130-year-old progressive movement’s efforts to use government to improve American society. It’s certainly interesting, but casual readers more interested in the here-and-now might prefer something shorter. I also wouldn’t get too hung up on Dunkelman’s Hamiltonian vs. Jeffersonian framework, as that distinction isn’t always as clear as Dunkelman would like it to be. For instance, Dunkelman considers Robert Moses a Hamiltonian figure, but Moses was also the New York City Parks and Recreation Commissioner, which is a very local position. More than anything else, Dunkelman’s Hamilton/Jefferson distinction is just shorthand for the difference between a system that emphasizes centralized planning and authority and a system that aims to keep power in check by empowering individual stakeholders.

No one reading this book is looking for a conceptual breakdown of Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian styles of governance, however. Per its title, readers will instead be drawn to this book to figure out “why nothing works,” and Dunkelman spends the second half of the book examining case studies that show how local and individual stakeholders have essentially exercised vetoes over public works projects. One chapter, for example, looks at the unglamorous topic of power lines. Because new green energy sources like windmills or geothermal plants are often located in places that aren’t connected to existing energy grids, new transmission lines need to be constructed to get that green energy to consumers. Yet few people want those power lines running across their backyards and farmland, and environmentalists don’t want them cutting through untouched wilderness areas. Our current regulatory system allows individual property owners and interest groups to delay or even stop such projects. Yet that also means an environmental group’s efforts to preserve a patch of wilderness also preserves society’s reliance on fossil fuels and keeps our planet on its current trajectory toward catastrophic global warming.

Dunkelman wants progressives to find a happy medium between their Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian impulses, but it’s unclear how to strike that balance. He devotes nearly his entire book to explaining the problem with progressivism’s swing to Jeffersonianism; what’s not present are examples of how other nations have greenlit public works projects while looking out for individual stakeholders. It seems Dunkelman would prefer an approach where central planners are empowered to weigh the costs and benefits of multiple plans, select the optimal option, and then receive clearance to complete the project as efficiently and effectively as possible. Dunkelman doesn’t embrace a full-on return to the unchecked leadership style of Robert Moses, whose projects were often shortsighted, racist, and harmful to neighborhoods, but he also argues if progressives insist citizens ought to trust government to deliver solutions while allowing public problems to fester due to their inability to exercise power on behalf of the people, the public will turn to demagogues like Donald Trump who promise that they alone can fix things.

Like Dunkelman, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson also focus on progressivism’s shortcomings in Abundance, one of the year’s buzziest new books. Abundance treads much of the same ground as Why Nothing Works but is more accessible for a general audience. It is, however, sketchier at times in its composition, even occasionally reading like a script for a TED Talk more intent on titillating its audience than informing it. I’d also add that if you’ve read Klein’s work for Vox or the New York Times or Thompson’s work for The Atlantic, you pretty much know what you’re in for.

Still, it’s good to have these arguments in one place, and if this is the first time you’re encountering these ideas, this is the place to start. Klein and Thompson are part of a new school of progressives who call themselves supply-side progressives. That handle may trigger some PTSD in liberals out there, but hear them out. Klein and Thompson argue the problem the United States faces today isn’t a matter of demand. People want green energy, more housing, better healthcare, etc. Furthermore, for the most part, subsidizing demand isn’t going to boost people’s ability to acquire those things. As Klein and Thompson see it, the problem is we’re not generating enough of the things people want. We’re short on supply, and because we’re not doing enough as a country to support the production of supply, our society has stagnated. We have chosen a world of scarcity over abundance.

Klein and Thompson’s solution is not to throw money at the problem (although they are not above using public funds to support innovation and development.) Instead, they want to peel away the rules, regulations, and bureaucratic mindsets that often prevent development from occurring. Like Dunkelman, they want government to get out of its own way so government can address public problems, to stop writing rules so government can start building things. They long to revise zoning regulations to make it easier to build multi-unit housing in residential neighborhoods, which in turn will make housing more affordable for middle- to low-income families and alleviate homelessness. By loosening regulations, they hope to make it easier to construct affordable, easily-accessible, and energy-efficient mass transit. While they acknowledge the means they are advocating for haven’t been embraced by progressives over the past fifty years, Klein and Thompson emphasize they serve progressive ends, which right now may be more important.

Abundance is a call to arms for progressives to use government not to block development but to once again do big things. One way Klein and Thompson sell readers on this vision is by imagining a future that isn’t just characterized by abundance and that hasn’t merely solved today’s problems but that is radically different than the world we inhabit today, one in which government support for research and innovation begets even further innovation and new technologies. Their striking introduction envisions a world twenty-five years from now in which local greenhouse skyscrapers grow both produce and lab-grown meat; low-orbit pharmaceutical factories manufacture wonder drugs; AI reliant on advanced microchips reduces the drudgery of work; and abundant clean energy generated by solar, wind, and nuclear fusion plants allow for the construction of desalinization facilities that water desert metropolises and restore the flow of overtaxed rivers. If that seems fanciful, Klein and Thompson remind readers that we went from a world that lacked electric power, automobiles, airplanes, aspirin, skyscrapers, bicycles, and motion pictures to one that did in roughly the same amount of time, and that all that innovation occurred at the dawn of the first progressive era. The difference today is that nearly all those above-mentioned innovations are already within our grasp; to get there, Klein and Thompson want progressives to ditch their antigrowth mindset and once again embrace the idea of, well, progress.

One thing about this political vision that will certainly terrify progressives is the possibility that a future Trump-like official will get his hands on this power and use government to raze forests, expand oil production, gut food safety agencies, target minority neighborhoods for commercial redevelopment, allow developers to construct unsafe housing, build a wall on the southern border, and go on a prison building spree. Like Dunkelman, Klein and Thompson don’t have a good answer for how to prevent that from happening. The basic problem is that if you empower government to do good things, you also empower it to do bad things. Klein and Thompson would simply counter that when you prevent government from doing bad things, you also prevent it from doing good things, and that’s the problem we’re facing right now. It’s hard to know if the country will be in the mood for a more active government once Trump is gone. Will Americans want to restrict a government they feel has grown too autocratic? Or is Trump a sign Americans are willing to embrace a more active government? Perhaps Americans will want more administrative expertise following Trump’s parade of fools. Or maybe Americans’ embrace of Trump is a sign they could care less about competence.

Klein and Thompson would like their book to serve as a rallying cry for the progressive movement and more effective governance. Barring a complete breakdown in public administration (which we’re flirting with as we speak) I’m skeptical the masses will flock to a Democratic Party promising better management of public affairs. Voters respond more positively to a candidate’s moral rather than managerial vision for the country. But voters also consider results, and if progressives promise the people that government can do important things and solve public problems, then progressives need to find a way to deliver. President Biden had the right idea when he pushed for an infrastructure and climate change bill; despite provisions meant to streamline its implementation, he still lacked a government that could swiftly enact it. As the authors point out, although Biden’s infrastructure bill allocated tens of billions of dollars for hundreds of thousands of electric vehicle charging stations, only around a dozen have been installed so far.

The arguments Dunkelman, Klein, and Thompson make are not new. Americans have long debated whether we ought to allow for a more active government or place greater restrictions on public authority. As progressives, however, what these authors want their progressive readers to realize is that they cannot have a robust regulatory state and a robust public service state at the same time, as the former will keep the latter from kicking into gear. Instead, they want their readers to accept that rules ought to guide but not block public actors. Furthermore, they urge their readers to understand the progressive agenda will ultimately require tradeoffs. For instance, it may be that a neighborhood, park, or wilderness area will need to be sacrificed for a greater environmental good. A rule or regulation shouldn’t keep a lone individual or interest group from preventing the government from achieving that progressive goal but instead guide planning and help the public judge whether our leaders are choosing the best available options.

Again, this is a problem progressives need to solve, because Republicans do not offer a strong alternative way forward. Most Republicans today do not take the task of governance seriously, and those who do typically default to a hands-off, let-the-market-solve-it approach. That anti-government mindset is a main reason the country is in its current state. Progressives are right when they argue government needs to step up to solve these problems, and their solutions are on-point. They just need to make government work again so that their solutions can pay off for the American people.

From my dining room window, I can watch construction workers across the street build a train station that will become part of the Purple Line light rail system connecting several Maryland suburbs near the DC border. It promises to alleviate traffic congestion, reduce automobile emissions, and provide a less-expensive form of transportation for low-income residents. It probably wouldn’t surprise you to learn the project has been in the works for over two decades now and is expected to come in five years overdue and $4 billion overbudget. It’s a good thing Montgomery County has undertaken such a project. Dunkelman, Klein, and Thompson would likely argue it is still within this progressive county’s capacity to do more and do better.

Signals and Noise…or maybe you should just buy yourself a subscription to The Atlantic

“The Only Way to Stop the Financial Crisis” by Annie Lowrey (The Atlantic)

“The Tariff Damage That Can’t Be Undone” by Rogé Karma (The Atlantic)

“The Investors Who Prop Up America Won’t Soon Forget This” by Rebecca Patterson (New York Times)

“There’s No Coming Back From Trump’s Tariff Disaster” by Jerusalem Demsas (The Atlantic)

“Trade Will Move on Without the United States” and “Why China Won’t Give In to Trump” by Michael Schuman (The Atlantic)

“Trump Is Stupid, Erratic and Weak” by Paul Krugman (Substack)

“Trump Brings Britain’s ‘Moron Premium’ to the U.S. Economy” by Paul Mason (The Atlantic)

“A Perfect Case for Congressional Action” by Conor Friedersdorf (The Atlantic)

“As Egg Prices Soared at the Supermarket, So Did Producer Profits” by Peter Whoriskey (Washington Post)

“What the Comfort Class Doesn’t Get” by Xochitl Gonzalez (The Atlantic)

“The Confrontation Between Trump and the Supreme Court Has Arrived” by Adam Serwer (The Atlantic)

“El Salvador’s Exceptional Prison State” by Gisela Salim-Peyer (The Atlantic)

“Trump is Already Undermining the Next Election” by Paul Rosenzweig (The Atlantic)

“The Problem With Abe Lincoln’s Face” by James Lundberg (The Atlantic)

Garbage Time: An NBA Postseason Preview

(Garbage Time theme song here)

This tells you how weird the 2024-25 NBA season has been: Nico Harrison still has a job but Michael Malone does not.

We’ll get to that in a bit. Before we do, however, let’s first mark the end of the NBA regular season, which concludes this afternoon. The playoff and play-in teams are set; all that remains up for grabs is seeding.

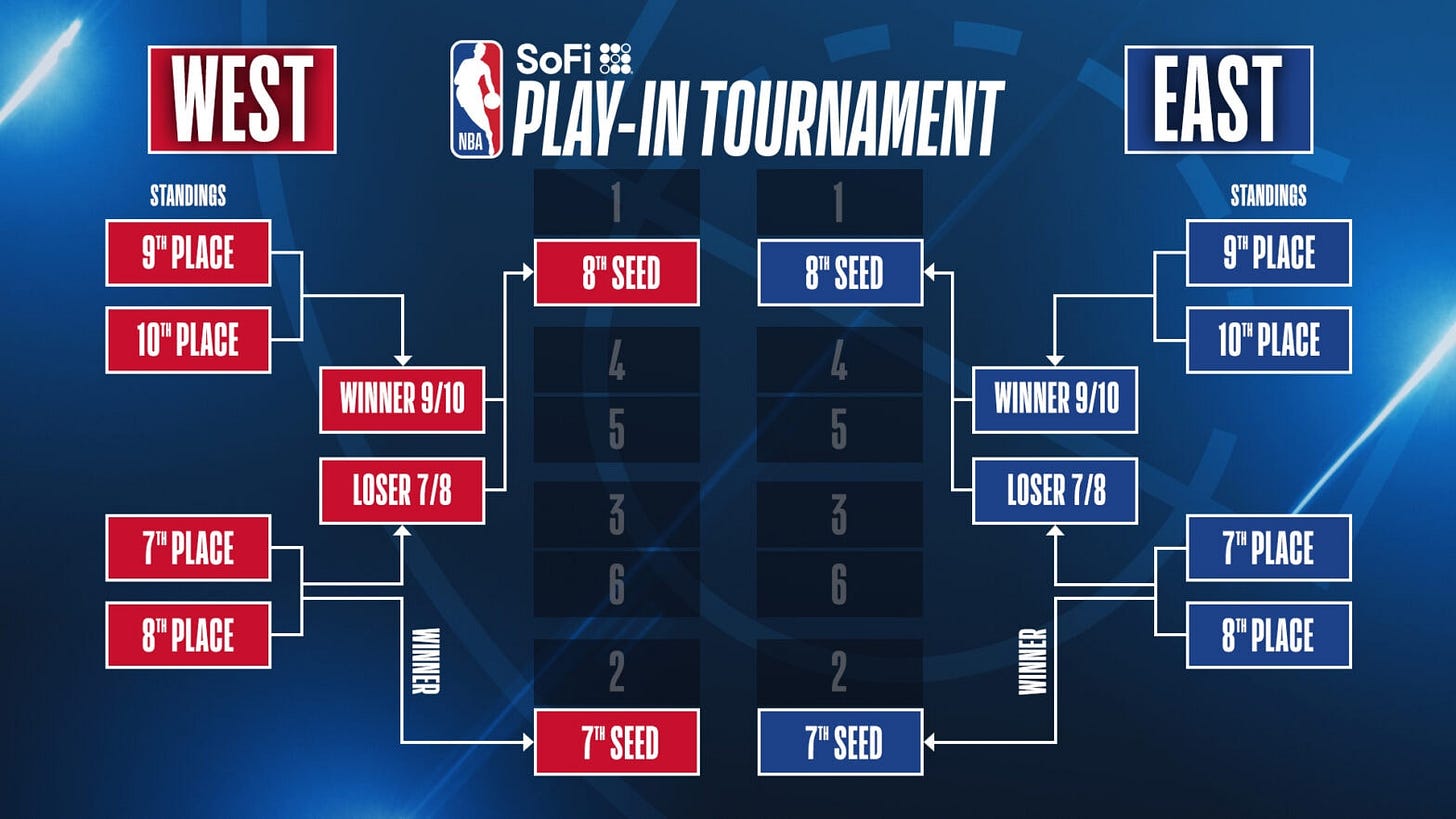

Speaking of the play-in, I would like to propose a rule change: Only teams with winning records get to play in the postseason. A few seasons ago, the NBA changed the postseason so that the teams seeded 7-10 had to play each other to make the playoffs. The winner of the game between seeds 7 and 8 advanced to the playoffs as the 7 seed, while the loser of that game then had to face off against the winner of the game between seeds 9 and 10 for the final playoff spot. The other two teams are eliminated from the playoffs. (If that’s confusing, here’s that paragraph in bracket form.)

The play-in tournament adds some do-or-die spice to the early days of the NBA postseason, but the stakes aren’t that high when the teams are underachievers whose most memorable moments didn’t air on SportsCenter’s Top Ten but during Shaqtin’-a-Fool. Of this year’s 7-10 seeds, the Hawks, Bulls, Heat, Kings, and Mavericks will all finish with losing records, while the Magic still have a chance to top .500 for the season. Who wants to watch Orlando, Atlanta, Chicago, and Miami duke it out for the honor of getting swept by Boston and Cleveland in the first round of the playoffs?

A worse scenario is unfolding in the Western Conference, where either the Nuggets (.605), Clippers (.605), Warriors (.593), or Timberwolves (.593)—all quality teams—will play Memphis (also a good team; .580) as 7 and 8 seeds. The loser of that game will then play a must-win game against either the sub-.500 Kings or Mavericks. The West is a Royal Rumble this year: No one would be surprised if any of the teams seeded 1-8 made the NBA Finals. Why ruin that potential by giving hapless Sacramento or Dallas the chance to crash that party?

As it has been for what seems like decades, the West is once again the best conference in the NBA. It’s also where most of the drama has been this season. The biggest news, of course, was the stunning trade that sent the Mavericks’ Luka Dončić to the Lakers for Anthony Davis. It’s easily the biggest trade in NBA history and it came completely out of the blue, so much so that Shams Charania, the ESPN reporter who broke the story, had to confirm on social media that the news was in fact real. After winning the Rookie of the Year award in 2019, Dončić was named first-team all-NBA for five consecutive seasons. Dončić is on track to become an all-time great NBA player, and at 26-years-old is just entering his prime.

The Mavericks received Anthony Davis from the Lakers in exchange for Dončić, but while Davis is an all-NBA player in his own right, he’s not the generation-defining player that Dončić is. Analysts overwhelmingly agreed that the acquisition of Dončić—who is now paired with LeBron James—was a steal for the Lakers. Now, there is a universe in which this trade makes sense for Dallas. Davis makes Dallas a stronger team defensively, and he slots in nicely alongside point guard Kyrie Irving. With Davis, the Mavs can still definitely contend for a title, although their title window is now smaller. There were also rumors that Dallas’s front office questioned Dončić’s fitness and conditioning and were reluctant to give a max salary to a player they didn’t trust to maximize his potential. If the future shows the Mavericks unloaded a problem, Dallas GM Nico Harrison may be forgiven for trading away their superstar. He’ll still catch flak for not getting more than just Davis in return for Dončić, though.

Currently, however, Harrison is the most despised man in the Dallas metroplex. He is booed relentlessly at American Airlines Center, and most assume it is only a matter of time until he is fired. Even if Dončić has personal problems, fans think that’s a problem the Mavs should have tried to fix rather than offload. It didn’t help either that the Mavs’ season fell apart when both Davis and Irving went down with injuries, while the Lakers, who many assumed would struggle mightily on defense with the addition of Dončić and the subtraction of the rim-protecting Davis, rose from the play-in to the 3-seed. The Lakers are suddenly title contenders again while the team that made the NBA Finals from the Western Conference just last season are also-rans.

The other major trade that went down at the trade deadline was the shipment of disgruntled Miami Heat star Jimmy Butler to the Golden State Warriors. Butler had grown unhappy in South Beach after Miami GM Pat Riley refused to offer him a contract extension even though Butler had led the Heat to two NBA Finals over the past five years. (Riley’s not crazy here; Butler is an oft-injured 35-years-old, and while he’s an all-star, he’s not the sort of player who’s a lock to make all-NBA.) Butler ended up demanding a trade and was suspended twice by the Heat for conduct detrimental to the team. It was a bad situation. Riley could have simply let Butler walk at the end of the season, but getting players back in exchange made more sense, but Riley lost a ton of leverage when Butler made it known he wanted out and would drag the team down with him if Miami didn’t grant his request.

Eventually Butler got flipped to the Warriors, who have gone 20-6 since acquiring him after starting the season 27-27. At first, analysts assumed Butler wouldn’t add much to the team, but it turns out pairing another legitimate scoring threat with Steph Curry is simply too much for defenses to handle. No team wants to take on Golden State in the postseason, especially if Playoff Jimmy comes out to play.

That Golden State remains mired in the middle of the Western Conference and fighting to stay out of the play-in is a testament to just how competitive the West is this year. It’s one of the reasons Memphis and Denver fired their coaches over the past couple weeks. Three seasons ago, Taylor Jenkins guided the Grizzlies to the league’s second-best record. Memphis hasn’t lived up to its full potential since then, in part due to the off-court antics of star Ja Morant. The Grizzlies have played well this season, however, winning nearly 60% of their games by utilizing an unusual offense that prioritizes spacing and cutting over pick-and-rolls. As the team’s fortunes declined in the second half, Jenkins began moving away from that offense, which apparently didn’t sit well with a front office that wanted to double-down on the approach.

As unusual as it was to see a team let their head coach go this late in the season, it was even stranger to see the Nuggets fire coach Michael Malone just this past week. Malone had guided Denver to an NBA championship just two years ago, and despite a rough second half, had the team poised once again to win fifty games. Yet Malone apparently had a rocky relationship with the team’s GM, which led to an unhappy locker room, and ownership decided to shake things up by letting both men go. It’s a sign of how urgent things are right now in Denver, where Nikola Jokić, the greatest player in the world and the third player ever to average a triple double for the season (how can he not win his fourth MVP this year?) is in his prime. With a player under contract who should have multiple titles to his name by the time his career is over, these are years the Nuggets feel they can’t waste.

All this is part of the pile-up in the Western Conference standings, where the teams seeded 2-8 have compiled impressive records and are within three games of one another in the standings. In addition to the Lakers, Nuggets, Warriors, and Grizzlies, there are the Houston Rockets, a young but inexperienced team, in the 2-seed; an overlooked LA Clippers team featuring a healthy Kawhi Leonard and James Harden; and a surging Minnesota Timberwolves team led by Anthony Edwards. Ensconced at the top of the standings and boasting a double-digit lead over the second-place Rockets, however, are the Oklahoma City Thunder. They’re led by MVP candidate Shai Gilgeous-Alexander and boast incredible depth. Strangely, however, their youth and inexperience doesn’t inspire fear in the hearts of the rest of the conference, where no one will be an easy out.

It’s a completely different story in the Eastern Conference, where there are only six good teams. Two of them, the overlooked Pacers and the overachieving Pistons, can’t be considered contenders yet, though. As for the Bucks, no team featuring Giannis Antetokounmpo should ever be counted out, but the Greek Freak will need to put his team on his back and hope point guard Damian Lillard can recover from a blood clot if Milwaukee is to make a deep run this postseason. And how about the 50-31 New York Knicks? Well, they’ve only one won game against a team with a better record and are a combined 0-8 against the two teams ahead of them in the Eastern Conference standings.

Those two teams are the Cleveland Cavaliers (64-17) and the defending champion Boston Celtics (60-21). The Cavs, who start four all-stars (Donovan Mitchell, Darius Garland, Evan Mobley, and Jarrett Allen) made one of the most consequential moves at the trade deadline when they acquired De’Andre Hunter from the Atlanta Hawks. Hunter was already in the running for Sixth Man of the Year as a Hawk and has only kept up the pace since arriving in Ohio. He’s the sort of player who can be a difference maker in a postseason series.

I’d still favor the Celtics to win the East, as their championship team from last year has returned intact. You can add an improved Payton Pritchard to Boston’s loaded roster this year, as the guard has emerged as a serious candidate for Sixth Man of the Year. Boston and Cleveland should face off against each other in the conference finals, but unlike last year’s second round matchup between the two teams, I don’t expect the Celtics will dispatch the Cavs in five games.

As for the Finals, I’ll stick with my preseason prediction: Celtics over Thunder. But the West is wild and more wide open than ever, and whoever is left standing there come June should give the Celtics a serious challenge. Expect a fun postseason.