Where Do Democrats Go From Here? Pt. 4: Exorcising the Ghost of Elections Past

PLUS: A review of "Juror #2" by Clint Eastwood, a tribute to Rickey Henderson, AND that time R2-D2 and Jon Bon Jovi joined forces to create (something like) a Christmas miracle

I’ve been voting for president since 1996. In that time, with one likely exception, I don’t think the American people have ever really voted for the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee.

You may think that’s an odd conclusion, because Democrats have won the popular vote in six of those eight elections (1996, 2000, 2008, 2012, 2016, 2020). Two of those times, however, the American people re-elected the Democratic incumbent (1996, 2012) so I’m not counting those given the electoral advantages that come with incumbency. In two other cases, Democrats won the popular vote but lost the electoral vote (2000, 2016) so I don’t consider those rousing affirmations of the Democratic brand. In 2020, Americans brought in a Democrat to clean up the incumbent Republican’s mess. (Along those same lines, 1992 feels more like a repudiation of a Republican president than an endorsement of a Democratic candidate.) That leaves 2008, which was definitely a rejection of a Republican administration but also the one time when it felt like the American people really did want the Democrats in charge.

In fact, 2008 is the one election in my lifetime when two non-incumbents were running for president and the Democratic candidate ended up in the White House. In the other four elections—1988, 2000, 2016, and 2024—the American people opted for the Republican. In the 2000 election, voters preferred a Republican candidate who actually touted his subpar intelligence as a personal attribute. In 2016 and 2024, voters turned to Donald Trump; I think you already know what I think of that guy and his qualifications.

It is almost as though a Republican president is the United States’ default setting. As if the only thing Americans believe Democrats are good for is fixing the country after Republicans break it. And then, once Democrats get the country back on the right track, voters run right back into the arms of the GOP.

There was a time lasting from 1932 to either 1968 or 1980 when Democrats were the nation’s default party. The Republican presidents during this era—Eisenhower and Nixon—were moderates (some would even argue liberal) on policy. The country leaned left.

That definitely changed (at least at the presidential level) in 1980. I have a very vague memory of that election. I was at my great aunt Lucille’s house in Waterloo, Iowa, on what I would learn later was Election Day. Lucille was very active in her union at the Rath meatpacking plant. She had a green Jimmy Carter poster in the front window of her house. Jimmy Carter did not do well that day.

A few months later, Ronald Reagan would declare in his inaugural address, “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” Democrats have been playing defense ever since.

The Republican Party is the United States’ default party because it is the party that loathes government in a nation that hates government. One would presume in a country like the United States that such a party would always have an advantage. Americans love freedom, and Americans tend to regard government as an entity that restricts freedom.

What Americans only tend to realize later is that when we view government as the problem and diminish it (anti-tax activist Grover Norquist often said he desired a government so small you could “drown it in a bathtub”) we often find ourselves at the mercy of private actors—employers, corporate monopolies, polluters—who, in their own way, deprive us of freedom. It is possible government can intervene to expand our freedom by, for instance, supplying us with an education, ensuring that we’re paid a decent wage, making sure the food and water we consume is safe, and guaranteeing us access to health care if we’re sick or hurt. That idea is at the core of what it means to be a Democrat.

I’m not going to get into the debate over limited “small” government vs. active “big” government, liberalism vs. conservatism. Both sides have their merits, and wise people on both sides of that divide understand the limits of their ideological perspectives.

I want to focus instead on the condition of the nation’s default political party, the Republican Party, a party that has pushed conservatism beyond its breaking point, a party now defined by its ineptitude and degeneracy. I’ve been writing about that problem in this Substack for years now. It was on display again this past week when House Republicans blew up a deal they had made with Democrats to keep the government open after the world’s richest man asserted his dominance over the Republican president-elect by taking to his social media platform and lighting the deal on fire. It’s déjà vu all over again, as the microscopic Republican House majority proved once more that they do not understand the political physics of a bicameral legislature within a system of separated powers.

“Government is not the solution to our problem,” Reagan said. “Government is the problem.” The problem with that outlook, however, is that we need government. We can certainly debate how much government we need, what it should do, and how it should do those things. But to put it that starkly—to claim that government is the problem—well, that may play well to the masses, but it undermines an essential social institution.

The more an elected official or public servant believes that government is the problem, the less likely it is they will be concerned with governance. They won’t be concerned with crafting good policy or with good administration. They’ll neglect important aspects of their duties and place little emphasis on expertise. Someone who thinks government is the problem will be more concerned with drowning it—killing it—than managing it well. That creates a vicious circle: The results of their poor management of government stand as proof that government is indeed the problem, which reinforces their anti-government crusade. We’ve seen this play itself out (and get progressively worse) from Reagan to Gingrich to Bush II to the Tea Party to the Trumpists.

It’s also always easier for a politician to run against the government than it is for a politician to campaign as a defender of government. Government is always doing wrong: Taxes are always too high, Congress is always spending too much money, deficits are always too big, corruption is always rampant, there’s always too much red tape, and the regular guy is always getting screwed. I won’t deny that government is flawed. We all have our frustrations with it. But as students of politics understand, these problems are often explicable. Understood from a certain perspective, they may not even be problems. It’s just difficult to explain why that is in a way concise enough to fit onto a bumper sticker or into a meme-worthy social media post.

There’s been a lot of soul-searching among Democrats following their defeat in the 2024 presidential election. Some have argued the party swung too hard to the left, that it’s too woke, that it is too eager to appease the establishment, that it has lost touch with the working class, that it doesn’t know how to effectively communicate with voters, that it is on the wrong side of popular opinion when it comes to inflation and immigration and trade, that voters can’t relate to their candidates, etc. Maybe a few of those reasons are true, maybe most of them are. I’ve shared my thoughts on the subject with you over the past few weeks, but I don’t know for sure.

But I do believe this: If Democrats want to go from being a negligent Republican Party’s clean-up crew to the nation’s default political party—a party that doesn’t just run even with Republicans but that establishes a durable national majority—it needs to convince Americans that government isn’t the problem but rather something that can be used as a force for good. To put it another way, it needs to exorcise the ghost of Ronald Reagan from American politics.

I thought we were headed in that direction in 2008, when the Republican Party had been discredited by both the war in Iraq and the onset of the Great Recession. But Democratic politicians at that time still felt constrained by the nation’s conservative inclinations, and then the Tea Party—and eventually Trump—emerged to channel the people’s anger at Washington. Yet even within Trumpism there is evidence the people want a more active, responsive government. While Trump’s corporate-friendly tax proposals and his DOGE initiative to scale back the size of government represent long-standing conservative desires, Trump’s protectionist immigration and tariff proposals are hardly Reagan-esque. There are also signs Republican politicians like JD Vance, Josh Hawley, and Marco Rubio are interested in developing a more worker-friendly Republican platform. The GOP is not a natural repository for such initiatives, but it is a sign the nation’s mood is shifting toward a preference for a more active government that can address economic inequality and the struggles of the working class. The Democrats shouldn’t shy away from that.

For now, however, it just feels like the nation is stuck in this back-and-forth during which voters keep defaulting back to the GOP as the nation’s preferred party when Republicans should have lost that mandate long ago. Republicans led this country into the war in Iraq. Conservative policies precipitated the Great Recession. Yet guess who Americans tend to say will do a better job managing foreign policy and the economy? Much of this is bound up in voters’ unquestioned assumptions about the GOP. So long as enough Americans think that the Republican Party is just supposed to be in charge, they’ll keep putting them in charge, no matter their woeful record. (As Bill Clinton said following Democrats’ 2002 midterm shellacking, “When people feel uncertain, they’d rather have someone strong and wrong than weak and right.”) While it should come as no surprise that government won’t work well when we keep putting vandals in charge of it, it should also come as no surprise that Americans keep returning the vandals to power when the vandals have convinced enough of us that they’re rightfully owed the job by virtue of being the most boss-like.

So Democrats need to convince voters the Republican Party should no longer be regarded as the nation’s default ruling party. The GOP’s poor record of governance will help make the case, as will, I suspect, Trump’s actions over the next four years. But for voters to then embrace Democrats as the nation’s new default party rather than as the party that gets to run the place while Republicans are in time-out, Democrats need to make the case for a return to an era of active government. They need to discredit the idea that government is the problem and instead insist that a government that is truly by the people should do all it can to make life better for the people.

To accomplish this, Democrats will need to rely on their diverse multicultural coalition and strengthen their appeal to working class voters. But even more importantly, I think they’ll finally turn the tide when they convince the middle-of-the-road Republicans who hold their nose as they vote for Trump that enough is enough, that MAGA is a threat to the nation’s stability and preeminence in the world, and that the Republican Party has therefore lost its mandate to govern.

Yet those middle-of-the-road Republicans must also come to this realization: That Democrats are not going to slide to the right to accommodate them. Instead, they must recognize that for decades, conservative policies have disproportionately favored the well-off while working class Americans either have struggled to make gains or fallen behind, and that it’s time to tip that scale back in favor of the working American. For instance, it may be that a federally-funded program that provides health care to every American is the price that must be paid for national stability. In other words, these uneasy Republicans will need to be persuaded that the best way to preserve American society is by embracing a liberal agenda.

And when that happens, I think that for the first time in my life, Americans will consistently begin voting for the Democratic Party.

In Memoriam: Rickey Henderson

News broke Saturday evening that baseball legend Rickey Henderson had passed away at the age of 65. Just six months ago, following the death of Willie Mays, I wrote an article in which I declared Henderson the greatest living baseball player. Here’s what I wrote:

[Henderson’s] not your prototypical modern-day great player who made hitting home runs the centerpiece of his game. Henderson’s greatest attribute was his all-around athleticism. He emphasized getting on base, using his speed to get around the bases, and scoring runs.

It’s worth breaking down each of those aspects of his game. First, Henderson got on base a little over 40% of the time. How did he do that? He did get over 3,000 hits, but also earned 2,190 walks, which can be attributed not only to his plate discipline, but also to a batting stance he developed to shrink the strike zone while retaining his ability to drive the ball. Second, Henderson is the career stolen base leader with 1,406 stolen bases, and it’s not even close; the player in second place, Lou Brock, stole 938 bases over the course of his career. (Henderson also leads MLB in caught stealing and holds a stolen base percentage of 80.8%, which puts him at 63rd all-time, but only fourteen other players ahead of him attempted more than 400 stolen bases over the course of their careers and none of those players had a higher stolen base percentage than 84.7%.) Finally, no one in MLB has scored more runs—the basic thing a team needs to do to win a game—than Henderson. It’s the record Henderson is most proud of.

Henderson played the game more like a dead-ball era player such as Ty Cobb (second all-time in runs), Tris Speaker, or Honus Wagner. But that doesn’t really capture Henderson’s profile, as none of those players hit more than 120 career home runs. Henderson hit nearly 300, most of which came from the lead-off spot; in fact, he hit 81 home runs to lead-off a game. An unusual combination of speed and power, Henderson is second all-time in power-speed #, sandwiched between [Barry] Bonds and Mays. That made Henderson the ultimate problem for an opposing team: A dangerous player to pitch to and a dangerous player to pitch around.

Baseball statistician Bill James once wrote, “If you split Rickey Henderson in half, you’d have two Hall of Famers.” Few players in the history of the game were as dynamic or exciting to watch. If you ask me who the greatest living baseball player is, I’m saying Rickey Henderson.

Henderson was also one of baseball’s most colorful players. He often referred to himself in the third person, such as when he was looking to sign with a team during the offseason and left this message with Padres general manager Kevin Towers: “Kevin, this is Rickey. Calling on behalf of Rickey. Rickey wants to play baseball.” He would rank alongside Yogi Berra and Casey Stengel for his verbal faux pas if only most of those tales were true. For instance, one of the most well-known stories about Henderson involved a conversation he had with first baseman John Olerud when they were both playing with the Mariners. Henderson asked Olerud why he wore a batting helmet while playing defense. Olerud said it was for protective reasons, as he had suffered an aneurysm as a child. Henderson then remarked that he had once played with a guy who did the same thing, to which Olerud—who had played with Henderson in Toronto—replied, “That was me, Rickey.” Great story, but both Henderson and Olerud will tell you it never happened. I guess there weren’t enough true stories about Henderson to fill his larger-than-life reputation.

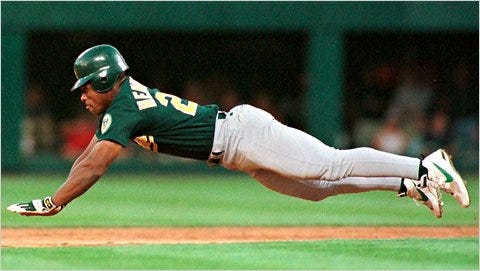

I was at the Baseball Hall of Fame a few years ago when I saw a pair of Henderson’s neon green batting gloves in a display case. (You can see them in the picture above.) They were the coolest things in the place. They immediately caused me to flash back to little league baseball. I don’t think anyone on my team wore batting gloves exactly like that, but we all wanted batting gloves, and we wanted cool-looking batting gloves, like Rickey. When we were stealing bases, we knew it was best to slide in feet first, but when we had the chance, we went in head first, like Rickey.

I didn’t realize until I saw those gloves how big of an influence Rickey Henderson had on me as a kid.

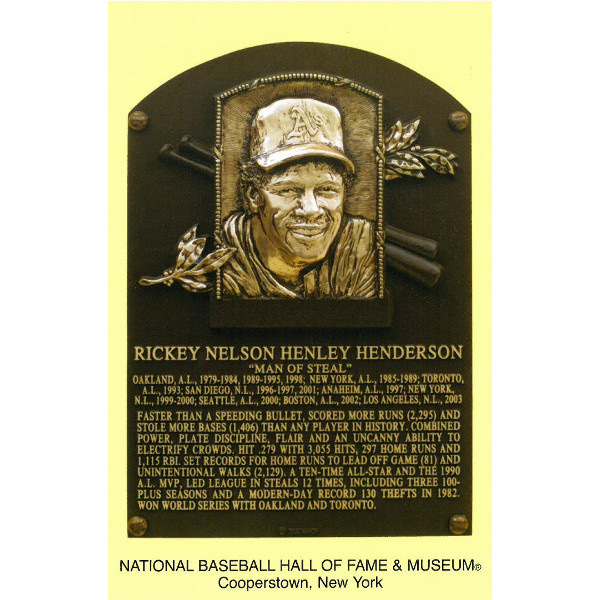

Henderson also has the coolest plaque in the Hall of Fame. Most players get run-of-the-mill write-ups about how they did this or that and how many times they did it. It makes a hall of extraordinary athletes seem very ordinary. But whoever wrote Henderson’s write-up decided the only way they could capture him was by implying he was something like a superhero:

Baseball players are often stoic figures. When the best players fail 70% of the time but a failure rate of 75% is considered bad, you better keep an even keel. I don’t think anyone would ever describe Rickey Henderson as stoic. He seemed to have figured out how to bend the fabric of baseball reality to his advantage. It’s what we wanted to do as kids, too, just grab that little extra bit of advantage that might somehow shrink the strike zone or let us take an extra base. That would have been cool, like Rickey.

For more on Henderson, check out Rickey: The Life and Legend of an American Original by Howard Bryant (2022)

Vincent’s Picks: Juror #2

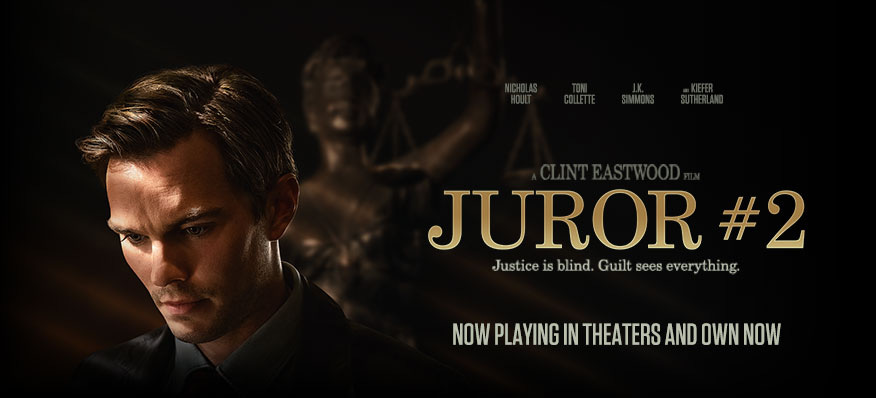

At the onset of voir dire in Clint Eastwood’s new film Juror #2 (now streaming on Max) the judge declares that, despite the jury system’s many flaws, it remains our best shot at delivering justice. By the end of the movie, you’ll be questioning that judge’s assessment.

“Juror #2” is Justin Kemp (Nicholas Hoult) a magazine writer in Savannah, Georgia. He initially tries to get out of jury duty by explaining to the judge that his wife Ally (Zoey Deutch) is in the third trimester of a difficult pregnancy. (Last year, the couple suffered a miscarriage, an experience that weighs heavily on both of them as their due date approaches.) Judge Hollub (Amy Aquino) believes the trial will conclude rapidly, however, and Justin ends up on the jury.

Justin has an unsettling personal connection to the case he is assigned to. The state has accused James Sythe (Gabriel Basso) of killing his girlfriend Kendall Carter (Francesca Eastwood) after they were seen fighting with one another at a local bar. Kendall’s body was found the next morning beneath a bridge. Assistant District Attorney Faith Killebrew (Toni Collette) argues James bludgeoned Kendall to death and then threw her body over the bridge into the ravine below.

As it turns out, Justin was also at the same bar that night. The date is burned into his memory because that was the due date of the twins his wife miscarried. He was at the bar because he was seeking solace in drink, something he had sworn off as a recovering alcoholic; fortunately, he found the strength not to take a sip. However, as he drove home through the pouring rain, he struck something on the same bridge Kendall’s body would be found beneath. When he stopped to inspect the damage to his vehicle, he was unable to find what he had hit. He assumed it had been a deer that fled away. Now Justin believes it more likely that he was responsible for Kendall’s death.

The state’s case seems pretty open and shut; Killebrew even brings a witness to the stand who testifies he saw Sythe at the scene of the crime. Justin is worried about coming forward, though, as a lawyer friend (Kiefer Sutherland) advises him the state won’t believe a recovering alcoholic even if he swears he didn’t have a drink and instead charge him with vehicular homicide. Justin opts instead to convince his fellow jurors to acquit Sythe.

A good portion of Juror #2 takes place inside the jury room a la Twelve Angry Men. It’s not exactly a recommendation of the jury system. Some take their duty seriously while others just kind of roll with it. One juror wants to wrap things up quickly so she can get home to her kids. Another is determined to throw Sythe behind bars because he bears the tattoos of a gang that destroyed the life of a family member. Some bring varying levels of expertise. A medical student points out Kendell’s body bears the marks of a hit and run, not a bludgeoning. Another, a fan of true crime stories, explains this case has all the hallmarks of the genre, suggesting to her Sythe is guilty, but concedes it lacks the typical twist that upends what everyone believes. A retired cop played by J.K. Simmons details all the flaws in the investigation and defies the judge’s instructions by researching leads on his own, which rattles Justin.

This is a straightforward film with no frills. It sometimes feels a little stagey and direct, particularly when the action shifts to the jury room, but Eastwood—who has a reputation as an efficient filmmaker—is here to get a thought-provoking script by Jonathan Abrams on film. Eastwood could have polished up or smoothed out a few scenes here or there, but as someone who’s been around a Hollywood production or two in his now ninety-four years, he knows the purpose of some scenes is to simply convey information. He’s content to let craft carry the day.

We are conditioned to treat the jury system—which brings together twelve citizens to sit in judgment of a peer accused of a crime and then determine if the state has proven his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt—with reverence. Eastwood seems to be arguing here that that institution as well as the broader legal system is only as good as the compromised and flawed people in it. We desire justice, but is that best attained by a system that compels prosecutors to run for office and overburdens public defenders? What are we to make of jurors who just follow the crowd or who take their responsibilities too seriously? A fascinating thing about Juror #2 is that Kendall Carter’s death is not the result of a crime, yet the system that is supposed to do right by her brings out so much that is less than admirable in those who participate in it that injustices abound. Juror #2 seems to say that truth and justice are not things we can trust institutions to produce. They are instead things we must have the courage to search for inside ourselves.

Top 5 Records Music Review: That Time R2-D2 and Jon Bon Jovi Joined Forces to Create (Something Like) a Christmas Miracle

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away Hell’s Kitchen.

The year was 1980. The Ayatollah Khomeini held 53 Americans hostage in Iran. A gallon of gas cost $1.19. Ronald Reagan won the presidency in a landslide. Mt. St. Helens erupted. TV viewers spent the summer wondering who shot JR. And the highest-grossing film in the United States was The Empire Strikes Back.

That film, of course, was a sequel to Star Wars (1977), whose cinematic significance is well-established. It also goes without saying that Star Wars has a very memorable soundtrack. This part of the “Main Title” is what’s playing in my head every time I pull onto the DC Beltway:

But I usually enter the Beltway at the Silver Spring/Wheaton interchange, which is a bottleneck, so I’m never able to make the jump to hyperspace. Delusions of grandeur, I suppose. Anyway, John Williams’ soundtrack was a huge hit in 1977, getting all the way up to #2 in September (it was denied the top spot by Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours) and earning a nomination for Album of the Year at the Grammys (where it was bested, once again, by Rumours.)

The “Main Theme” fared better on the singles chart, but in a more roundabout way. Record producer, musician, and science-fiction aficionado Domenico Monardo had attended Star Wars on opening night and by the next evening had seen the film four more times. Monardo is an interesting guy. A trombone player like his father, Monardo attended the Eastman School of Music in Rochester with Chuck Mangione (“Feels So Good”) and Ron Carter before enrolling in (you’re thinking it’s going to be something like Julliard but it’s not) the United States Military Academy at West Point. Once he had completed his service, Monardo moved to New York and joined a jazz quartet, but upon hearing the song (you’re thinking it’s going to be “A Hard Day’s Night” or “Like a Rolling Stone” or “Be My Baby” but it’s not) “Downtown” by Petula Clark, decided to pursue a career in pop music. He would end up arranging the horns on “Crystal Blue Persuasion” (1969) by Tommy James and the Shondells and playing the trombone solo (yes, a trombone solo) on Diana Ross’s 1980 smash (and LGBTQ anthem) “I’m Coming Out”, a song co-produced by Monardo’s neighbor, Chic’s Nile Rodgers.

Chic was a disco band, and as it turned out, Monardo had a thing for disco. In 1973, he formed the Disco Corporation of America production company with two other associates and co-produced Gloria Gaynor’s 1974 early disco hit “Never Can Say Goodbye”. After seeing Star Wars in 1977, Monardo had an [insert your own adjective here] idea: What if I turned the Star Wars theme into a super fly disco track we could all dance to? Monardo ran the idea by Neil Bogart of Casablanca Records (the home of Kiss, Parliament, and a number of disco acts like Donna Summer) who only greenlit the project after the motion picture soundtrack began ascending the charts.

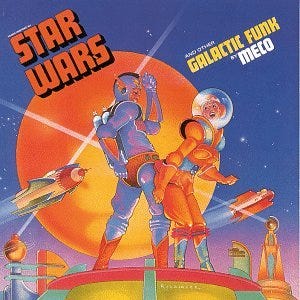

The result was Star Wars and Other Galactic Funk, a disco and jazz fusion album Monardo released under the name Meco.

The album only got up to #13 but originally outsold the Star Wars soundtrack. The lead single, however—“Star Wars Theme/Cantina Band”, a Frankenstein’s medley of music passing as Wagnerian opera, Dixieland jazz, and guitar rock slathered with 4-on-the-floor disco beats—went to #1 as Williams’ main theme was peaking at #10. (Williams, however, would beat Meco at the Grammy’s for Best Pop Instrumental Performance.) “Star Wars Theme/Cantina Band” held on to the top spot for two weeks that fall before it was dethroned by (I have a bad feeling about this) Debby Boone’s “You Light Up My Life”.

By the way, the album cover was drawn by Robert Rodriquez, a folk music fan who hated disco. Rodriquez is most famous for creating the wholesome and iconic artwork for the Quaker Oats company in the 1970s. If you’re like me, I know what you’re thinking about that cover: Why did Rocket Man decide to slap a pair of non-whitey tighties on over his spacesuit? Who does this guy think he is, Tony Manero of the 25th Century?

Flash forward to 1980. Monardo, as Meco, had made a name for himself by “Meco-izing” other soundtracks, including Close Encounters of the Third Kind, The Wizard of Oz, and Superman. He had also put together an EP of music drawn from The Empire Strikes Back. But Monardo had been working on another idea by the time Empire was released: A Star Wars Christmas album, one that he hoped would be the first in a series of annual holiday-themed Star Wars releases.

One would think Star Wars and Christmas would go together like ribbons and bows; after all, they’re both the story of a kid who grows up in the desert, learns a shocking truth about his real father, and is then expected to save the universe. But Star Wars and Christmas have a very mixed record. On the plus side, roughly 50% of the toys in Santa’s sleigh from the late 1970s through the mid 1980s were Star Wars toys, and I know this from personal experience and loved it. When I was older, I remember going to my aunt and uncle’s house for Christmas and watching the annual Star Wars marathon on the USA Network, which was a treat. Also good Star Wars + Christmas memories: The Force Awakens.

Not as positive: Many would say The Last Jedi and The Rise of Skywalker. But definitely the 1978 Star Wars Holiday Special, which is so bad it has been denied an official release. (If you’re curious, you can watch it here.) Starring the main cast of Star Wars, the special follows Han Solo and Chewbacca’s attempt to return to Chewie’s family on his home planet of Kashyyyk so the Wookiee and his family can celebrate “Life Day” together. (Do they not celebrate Christmas in space? If Jesus is the only son of God, and God reigns supreme over all of Creation, including outer space, I think Jesus would kind of be a big deal everywhere. Do the Disco Jetsons getting down to Meco’s galactic funk on that album cover worship Jesus? The way they’re shaking their booties, they probably need some Jesus in their lives.) A lot more happens in the special: Stormtroopers show up, we meet Chewbacca’s dad Itchy and his son Lumpy, Art Carney provides comic relief, Harvey Korman does a parody of Julia Child, Bea Arthur sings a song at the Mos Eisley cantina, Jefferson Starship (in what would be Marty Balin’s last appearance with the band until the 1990s) are featured in a video, and there are glowing orbs. It’s bantha poodoo. The special’s one redeeming quality is a cartoon that marks the first official appearance of Boba Fett.

So yeah, Monardo deciding he should take another crack at fusing Star Wars with Christmas less than a year after the disastrous holiday special may strike many as demented, but Meco was still riding high off Galactic Funk; if anyone could do it, it was probably him. Because I can only assume Jefferson Starship was putting the finishing touches on “Jane” and therefore unavailable, Monardo got Yale professor Maury Yeston to write most of the album’s music and lyrics. Now lest you think that’s about as wise as trusting Lando Calrissian to keep you safe upon your arrival in Cloud City, just remember Yeston went on to win the Tony Award for Best Original Score for both Nine (1982) and Titanic (1997), both of which also won the Tony for Best Musical. Yeston, who began working on the album without knowing anything about The Empire Strikes Back and who had a seven-year-old son who was a huge Star Wars fan, decided to keep the mood of the record silly and festive for the kids, so the album doesn’t quite match the whole Han Solo frozen in carbonite/Darth Vader just cut off Luke’s hand/Wait, did Luke’s dad just cut off his hand? vibe of Empire, but whatever, Star Wars is supposed to be fun.

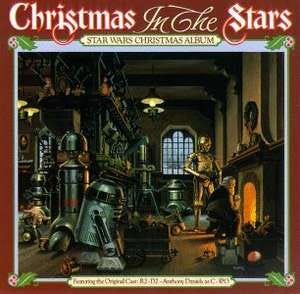

Hence Christmas in the Stars: Star Wars Christmas Album by Meco, which hit record store shelves in November 1980.

The album is about a factory where droids manufacture (presumably officially licensed Kenner-brand Star Wars) toys for Santa Claus, proving in the process that automation has gutted the working class. Nearly the entire album is sung and narrated by C-3PO (Anthony Daniels) which is great if you’re really into everyone’s least favorite Star Wars main character. (Why can’t it be narrated by R2-D2? Can someone explain to me why a civilization that can build the Death Star can’t figure how to connect a device similar to what allows Threepio to speak to Artoo so astromech droids can talk using actual words instead of beeps? Because it would be way cooler listening to the spunky and sassy R2 singing and telling a story than his neurotic English butler sidekick. I’ll bet if R2-D2 sang on that record, it would sound like this.)

According to Wikipedia, the only single from the album, “What Can You Get a Wookiee for Christmas (When He Already Owns a Comb)” (sung by Yeston himself) became “a recurring top-40 Christmas hit.” I don’t think that’s true. My guess is you’ve never even heard that song before.

But I find the whole premise of the song offensive. Why are we reducing Wookiees to their hirsute nature? Perhaps Chewbacca would enjoy a gift certificate to Ponderosa or a copy of the hot new REO Speedwagon album or a fondue set. I’m sure Chewie has a very active inner life and enjoys reading, so why not John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces or (this would be right up his alley) Cosmos by Carl Sagan? I know he enjoys playing Dejarik, so maybe, I don’t know, Simon, or how about an Atari? He’d probably like Pac-Man (but maybe just stay away from Asteroids; could be traumatic.) Or how about a freaking medal for Christ’s sake? That’s what you can get a Wookiee when he already owns a comb.

(Warning: Explicit subtitles)

Also, wouldn’t it be ironic if, for Christmas, Chewbacca wanted to get Han a new hyperdrive motivator for the Millennium Falcon but didn’t have enough money so he sold all his hair to buy one but when he gave Han the gift it turned out Han had sold the Millennium Falcon so he could afford to buy Chewbacca a nice set of ornamental combs for his hair. I know you’re probably hung up right now on the thought of a hairless Wookiee, but come on, get past that to the moral of the story. That right there, folks, is the true meaning of Christmas. I’m tearing up thinking about it; well, that and a hairless Wookiee.

But enough with the digressions, because this is where things start to get epic. Meco recorded Christmas in the Stars: Star Wars Christmas Album in a New York City studio called Power Station, so named because it was housed in a former ConEd power plant in Hell’s Kitchen. The co-owner of the studio was one Tony Bongiovi, who co-founded Disco Corporation of America with Menardo and helped produce Star Wars and Other Galactic Funk. Tony Bongiovi was the real-deal. His inquisitive nature as an up-and-coming record producer got him invited to Motown’s studio in Detroit when he was only 17-years-old. Shortly thereafter, he worked with Frank Zappa and helped Jimi Hendrix record Electric Ladyland. During the 1970s, he collaborated with Holland-Dozier-Holland on “Band of Gold” by Freda Payne and produced the seminal 1977 punk albums Leave Home and Rocket to Russia by the Ramones and Talking Heads: 77 by Talking Heads. Bongiovi’s Power Station became an in-demand studio in the 1980s where albums such as Risqué by Chic, The River and portions of Born In the U.S.A. by Bruce Springsteen, Diana by Diana Ross, Let’s Dance by David Bowie, and Like a Virgin by Madonna were recorded.

Menardo and Bongiovi were at Power Station working on Christmas in the Stars when they ran into a bit of a problem on a number titled “R2-D2 We Wish You a Merry Christmas”, the song that would become the B-side to “What Can You Get a Wookiee for Christmas (When He Already Owns a Comb)”. Like “What Can You Get a Wookiee…”, Daniels wasn’t expected to sing this particular song. Instead, Menardo and Bongiovi wanted it sung from the perspective of a kid. The problem was that the three singers they brought in to sing it all sounded too old.

After a few failed attempts at capturing the magic of a Star Wars Christmas, Menardo and Bongiovi landed upon an idea: Why not see if Bongiovi’s 17-to-18-year-old cousin John could step into the studio to sing the song? John, who possessed a higher-pitched voice than the others who had attempted the track, had played in bands in his native New Jersey throughout his teenaged years and dreamt of making it big in the music industry. Tony let him hang around Power Station, where John ran errands for his cousin and learned the ropes of the recording industry. John was humbly sweeping floors in the studio when Tony asked him to step behind the mic and record the vocals for “R2-D2 We Wish You a Merry Christmas”. I can only imagine John said he’d Give. It. A. Shot. (Snare!) John’s take worked, and the song made it to record.

Christmas in the Stars was a success, but only about 150,000 copies of the album were sold before the album’s record label RSO had to shut down due to a lawsuit filed by (I may be wrong on this, but I think this is right) the Bee Gees. “What Can You Get a Wookiee for Christmas (When He Already Owns a Comb)” by the Star Wars Intergalactic Droid Choir & Chorale was released as a single in 1980 but peaked at #69. Meco wouldn’t get the chance to record his series of Christmas-themed Star Wars albums, although following the release of Return of the Jedi in 1983, he would release the album Ewok Celebration (whose hip-hop-influenced title track climbed to #60 on the Billboard charts. The song features an Ewokese rap by Duke Bootee, who in the previous year had co-written one of the most influential rap songs of all-time, “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five.)

But “R2-D2 We Wish You a Merry Christmas” would go down in rock and roll history. That song’s vocalist, John Bongiovi, would spend the next two years sending demos around to record labels. He had no takers until a suburban New York radio station latched on to “Runaway”, a song he had recorded with a group of session musicians that included Roy Bittan of the E Street Band. “Runaway” got John a record deal. Then John got himself a band. Then his record label gave that band a name. John became Jon, and the next time he stepped in front of a mic at Power Station with his cousin Tony Bongiovi behind the boards, he did so as the lead singer of Bon Jovi. Since that fateful day, he’s seen a million faces.

And rocked them all.

That’s right: Rock and Roll Hall of Famer Jon Bon Jovi’s first recording credit (billed as “John Bongiovi”) was for “R2-D2 We Wish You a Merry Christmas” from 1980’s Christmas in the Stars: Star Wars Christmas Album by Meco. He was paid $183 for it, which seems simultaneously excessive and inadequate.

Is there a lesson to be gleaned from all this? I’m not sure, but if there is, it may be this: Even if you grow up in an imperial backwater (Judea, Tatooine, New Jersey) you can still hit the big time.

Merry Christmas, Have a Nice Day, and May the Force be with You.