When Does Political Theater Become Political Crime?

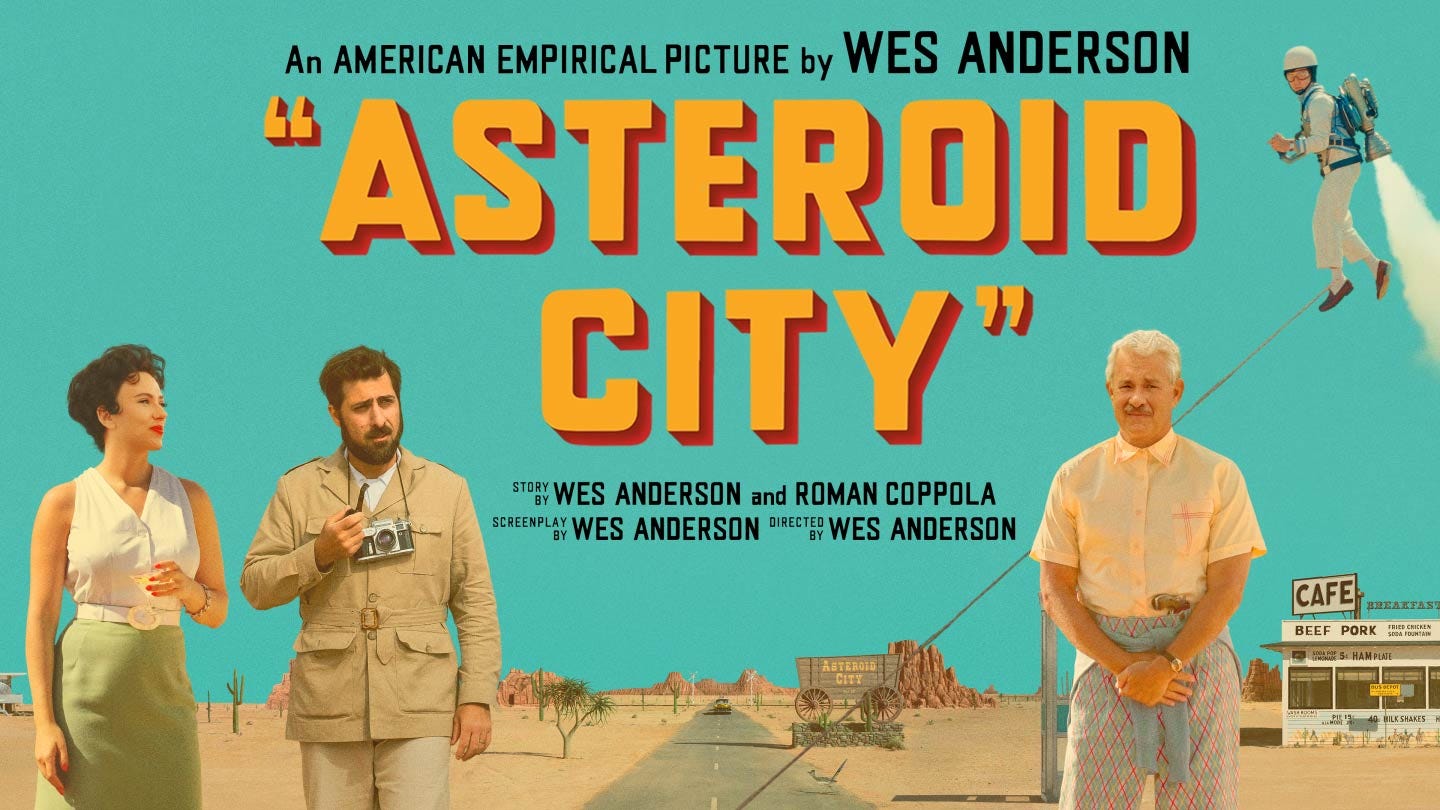

PLUS: A review of Wes Anderson's "Asteroid City"

Republican Senator Lindsey “Goose” Graham of South Carolina uncorked a doozy this week. Appearing on FOX News the night Don Trump was indicted in Georgia for attempting to subvert the results of that state’s 2020 presidential election, Graham was asked how Trump could effectively run for president in 2024 if Trump had to constantly shuttle back and forth between four east coast courtrooms. Graham responded

He's spending more money on lawyer fees than he is running for office. January 6th, I was there, I saw it, he was impeached over it. The American people can decide whether they want him to be president or not. This should be decided at the ballot box, not a bunch of liberal jurisdictions trying to put the man in jail. They’re weaponizing the law in this country, they’re trying to take Donald Trump down, and this is setting a bad precedent, and what I fear is that you’re changing the way the game is played in America, and there’s no going back. We’re in for a very hard time if this becomes the norm.

The emphasis there is mine. What Goose seems to…forget? ignore? not give a damn about? is that if Trump had had his way in the waning days of his presidency, the 2020 election would not have been “decided at the ballot box” but through a series of deceptive and constitutionally sketchy hardball political maneuvers that would have shattered any notion that the people pick their president in this country. It was Trump who sought to “weaponize the law” (and incite a riot) in the aftermath of the 2020 election, Trump who was setting a “bad precedent” by trying to steal an election, Trump who attempted to “change the way the game is played in America.” If Goose is so concerned about the prosecution of presidents becoming “the norm,” maybe he ought to take a long hard look at just how abnormal Trump’s presidency was. That’s how we’ve reached our current moment in American history.

So yeah, Goose stepped in it by invoking the sanctity of the ballot box to defend a man who regards the ballot box as an obstacle to power. But there is a concern Goose is alluding to here that needs to be taken seriously: That the indictments issued by special prosecutor Jack Smith and Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis are criminalizing political activity. That issue matters because if this case goes to trial and Trump is found guilty of a conspiracy to defraud the United States, the Supreme Court will likely get the final word on that verdict. Their decision will likely hinge on whether Trump’s actions merely amounted to political theater or crossed the line into political crime.

A few things before I explore that question. First, while writing about this topic, I’m going to stick with Smith’s indictment because that’s the federal case, making it the biggest hammer being swung by law enforcement. Second, I’m not going to dive into the wisdom of prosecuting a former president. We’re already travelling down that road. Instead, I’ll stick to an analysis of the charges. Finally, I’m taking as a given that what Trump did after losing the election was profoundly wrong and ought to disqualify him in the mind of any reasonable American from ever again serving in public office. The question I’m raising isn’t if what Trump did was wrong but if it was a crime.

Reckoning with this question means reckoning with some uncomfortable truths about politics. To help me with that, I’m going to turn to an essay titled “Lying in Politics” written by Hannah Arendt in 1972 following the publication of the Pentagon Papers, which revealed the U.S. government had been lying for years about the conduct of and prospects for success in the Vietnam War. Arendt’s theory of politics is that politics is action: People coming together to speak and interact in public. This act affirms their freedom as individuals and creates a unique political space defined by the interactions of the people. We can see this sort of political action occurring when people create (or “constitute”) a government, when they craft laws “in congress” with one another, and in social movements.

A key point here is that politics is a creative undertaking. It’s about humans looking at their world and believing it could be different if they worked with others to make it so. To pull that off, people often have to assert claims that, at the time, may not only appear preposterous but intellectually dubious, i.e., that slavery, segregation, and colonialism are not the natural order of the world; that workers have rights and shouldn’t be exploited by their employers; that women are the social equals of men; that LGBTQ couples ought to be able to marry one another; that health care is a right; that we should take major action to stop the planet from overheating. “We are free to change the world and to start something new in it,” Arendt writes. “Without the mental freedom to deny or affirm existence…no action would be possible; and action is of course the very stuff politics are made of.”

But, as Arendt adds, the connection between creativity and politics comes with a catch:

[C]hange would be impossible if we could not mentally remove ourselves from where we physically are located and imagine that things might as well be different from what they actually are. In other words, the deliberative denial of factual truth—the ability to lie—and the capacity to change facts—the ability to act—are interconnected; they owe their existence to the same source: imagination.

In other words, the essential imaginative element of politics that empowers us to dream about a “more perfect union” or a “new birth of freedom” or a day when our “children will…live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character” is the same imaginative element that enables politicians and citizens to spin facts, propagate ideas unsupported by evidence, tout conspiracy theories, and lie. It’s why honesty has never been counted among the political virtues. As much as we may despise misleading political speech, we wouldn’t want to live in a political world where authorities policed political speech to ensure everything everyone said on a political topic was verifiably true. (“Are your taxes too high? Is inequality too high? Prove it.”) Like so much in politics, the features essential to its functioning (in this case, creativity and imagination) also allow for abuse. We have to take the good with the bad.

One can make the case Trump, as a serial fabulist, is the most “imaginative” American president ever. In the initial rush to defend Trump against Smith’s charges, his apologists pointed out it is not a crime—even for a president—to lie; Trump could legally claim the 2020 election was stolen from him even if he knew that wasn’t true and others had informed him his claims were false. But Smith heads this argument off in his indictment by admitting as much (“[Trump] had a right, like every American, to speak publicly about the election and even to claim, falsely, that there had been outcome-determinative fraud during the election and that he had won.”) What Smith argues instead is that the lies were part of a criminal conspiracy to overturn the legitimate results of the 2020 election. Trump and his accomplices lied about the existence of widespread election fraud in order to convince others to act in their own official or independent capacity to subvert the election’s outcome.

That’s how fraud works: Convince someone that what you’ve said is true, and then use the trust that individual has placed in you to fleece them. Speech used to commit fraud isn’t protected by the First Amendment. Instead, such speech is considered part of the fraudulent action. That’s why Trump is in such serious legal peril at the moment: It’s not just the speech, but his attempts to submit false slates of electoral college electors to Congress, corrupt Vice President Pence and officials in the Justice Department by encouraging them to act on his lies, and disrupt an official meeting of Congress by whipping a mob into a frenzy and directing its anger at the Capitol.

But while commentary about this case has so far centered on whether the First Amendment protects Trump’s conduct in the aftermath of the 2020 election, I suspect Trump’s lawyers are going to mount a broader defense: That Trump’s speech and actions do not amount to fraud but constitute a form of creative political theater protected by the First Amendment’s provisions concerning the rights to free speech, assembly, and to petition the government. Taken together, those provisions create a political democracy, one in which citizens and politicians can speak and act with one another to advance an original political agenda. Trump’s lawyers would argue that while the events at the Capitol on 1/6 got out of hand, everything Trump did following the election was permissible political activity. Finding Trump guilty of these charges would amount to criminalizing political activity, which would have a chilling effect on the political life of the nation.

Trump’s lawyers would begin by addressing the lies, which they will defend as “theories.” (Smith proves this for Trump’s lawyers by quoting alleged co-conspirator Rudolph Giuliani, who, when questioned about his lack of evidence to support his claims about a stolen election, states, “We don’t have the evidence, but we have lots of theories.”) Politicians and citizens have based their actions on “theories” in the past: Social Darwinism, socialism and communism, trickle-down economics, critical race theory. Jefferson and Hamilton had competing theories about democracy that shaped politics in the early days of the republic. Arendt’s article critiques the folly of believing one such theory—the domino theory—at the expense of a reality-based assessment of that theory. But no matter how ridiculous or noncredible or fantastic such a theory may be, no politician in America should be punished for believing in and acting in accordance with a theory.

Some may counter that Trump pushed a particularly outlandish theory he knew to be false: That rampant voter fraud occurs in urban Democratic strongholds in the United States. Trump’s lawyers would respond that many conservatives like Trump believe that theory, and that the reason they can’t definitively prove their claim is because they believe the voting systems in those areas are designed to conceal fraud. Yes, that means refuting Trump’s theory would require someone to prove a negative—that super-secret voter fraud doesn’t exist—but that’s really beside the point, because Trump’s attorneys would argue that, at the end of the day, Trump and every other citizen can believe any political theory they want and act in accordance with it regardless of its epistemological validity.

Consequently, everything Trump did after establishing his belief in widespread voter fraud can be seen as a political effort to persuade people to accept and act upon his theory of the 2020 election. Much of it took the form of political theater designed to dramatize his claims. The slates of alternate electors were not meant to be slipped surreptitiously into the record but to show what would have happened had the votes in those states been counted accurately and create the political tension that would have prodded Congress to deal with Trump’s arguments. Trump’s attempts to “corrupt” the DOJ and Vice President Pence were actually passionate attempts to “persuade” them to recognize the political (if not factual) validity of his theories. Trump never ordered anyone to violate their oaths but tried to convince them to see things from his and his supporters’ point of view. The rally on the Ellipse was a way to compel Congress to reckon with the people. (It only got out of hand when they left Trump and relocated to the Capitol.) These were all political actions undertaken for a political purpose.

Finally, what Trump asked state legislators, Congress, the DOJ, and Vice President Pence to do wasn’t to commit fraud but to take (admittedly extraordinary) constitutional actions. Trump wanted officials to declare that, given Trump’s theory, there was reason enough to believe the results weren’t valid so that state legislatures and Congress might feel compelled to resolve the issue. The Independent State Legislature theory that would have allowed state legislatures to override the will of the people may not have passed muster with the Supreme Court this summer, but it had adherents, even on the Court. Sincerely believing in the constitutionality of that theory therefore is not an act of fraud. Neither is asking Vice President Pence to act in an arguably constitutional way by objecting to the counting of some states’ electoral votes, which would have forced the House of Representatives to act in accordance with the Constitution and select the winner of the 2020 election. None of that presumed Congress at the end of the day would have picked Trump. Instead, Trump was acting politically to encourage politicians to follow this political (and presumably constitutional) path forward.

Ultimately, I think that will be Trump’s defense: That he was playing political hardball and engaged in political theater, and that the place to confront Trump politically is on the field of political battle, not in a criminal courtroom. To throw him in jail for acting politically—even when many object to the validity of the theories motivating his actions—would have a chilling effect on political activity in the United States. If that happened, individuals could be charged with fraud and imprisoned for propagating unpopular theories and trying to convince others to act in accordance with those theories. Criminalizing that sort of behavior would rob politics of its essential creative spark.

Smith may have enough on Trump regardless. The accusations against Trump concerning his attempts to convince Justice Department officials to violate their oaths of office by lying about the results of their inquiries into the 2020 election are damning, and the events of 1/6 shouldn’t merely be understood for what they are but for what they could have been: A bloodbath. It would be hard to refute the evidence Smith has gathered against Trump.

Ultimately, however, Smith will probably end up defending his case before the Supreme Court, whose justices will want to know where to draw the line between political theater and political crime and if throwing Trump in jail on charges of fraud connected to political actions might also lead to the imprisonment of other politicians and activists motivated by unpopular theories and engaged in dramatic political acts. Could a president be imprisoned for promising voters to forgive student loans despite evidence the president knew doing so would be ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court? Could a candidate be jailed for calling for and seeking a recount of votes that the Supreme Court eventually concluded would have denied citizens of equal protection under the law? Could that candidate’s opponent be locked up for staging a protest intended to intimidate public officials and make it appear as though the public had rallied to his side? What might happen to activists who advocate for the violation of political norms or extreme political acts that would decisively tip the balance of power to their preferred side? Could they be accused of attempting to “defraud” their opponents of political power? Would such a law lead to the suppression of creative, novel, and radical political opinions and tactics?

Smith would need to articulate some controlling principle that would place limits on prosecutions of this kind. It may be that Trump’s case is exceptional, making those limits easy to specify. (Smith may be alluding to this in his indictment when he admits candidates have the right to challenge electoral results in courts of law. Trump’s crime seems to be subverting the electoral process itself through fraud. Smith may argue speech and actions on this topic deserve greater scrutiny since they cut to the core of democratic functioning in this country.) But because these charges are unprecedented in American history, there’s the risk this case could establish an untested precedent that proves poisonous to our politics. Maybe that will make prosecutions of so-called political fraud an issue the Court rules out of bounds.

So Goose actually could have a point here. As much as I despise what Trump did in the aftermath of the 2020 election, I’m not sure it’s an issue that can be adequately addressed in the courts. The best way to handle an anti-democratic strongman like Trump is for every citizen to reject him and his brand of politics. The fact that Goose Graham can’t build up the courage to do exactly that reveals he’s as much a part of the problem as Trump is.

PS: Since Smith alleges Trump was part of a criminal “conspiracy” to defraud the United States and its people, I found this line in his indictment rather curious:

When the Acting Attorney General told [Trump] that the Justice Department could not and would not change the outcome of the election, [Trump] responded, “Just say that the election was corrupt and leave the rest to me and the Republican congressmen.”

Wait, does that mean “the Republican congressmen” were in on this conspiracy too? We know representatives Paul Gosar, Jody Hice, Marjorie Taylor Greene, Mo Brooks, Scott Perry, and Louie Gohmert and senators Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley objected to the certification of some states’ votes. (Sen. Kelly Loeffler withdrew hers.) Over one hundred Republicans across both houses of Congress (including then-House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy) voted for rejecting Pennsylvania and Arizona’s electoral votes even after the insurrection. Following the riot, Rudy Giuliani erroneously left a message on Utah Senator Mike Lee’s phone intended for Alabama Senator Tommy Tuberville begging him to find a way to push certification to the next day. It’s hard to believe Tuberville was the only member of Congress Trump and Giuliani were coordinating with.

And let’s not forget about the actions of one Lindsey “Goose” Graham, who called Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger in November 2020 to inquire about signature errors on ballots. According to Raffensperger, Graham implied Raffensperger should, “Look hard and see how many ballots you could throw out.”

Beyond his co-conspirators, Trump attempted to enlist state legislators, DOJ officials, and the vice president in his conspiracy. But there’s no way his scheme works without the help of Congress. The indictments don’t go there. What story would they tell if they did?

Intermission: “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” by the Band (1969, clip from the 1978 film The Last Waltz) R.I.P. Robbie Robertson

Here’s Robertson explaining the origins of that song.

Signals and Noise

By Ben Jennings of The Guardian:

CNN reports prosecutors in Georgia have evidence connecting Don Trump’s legal team to the early January 2021 voting system breach in Coffee County, Georgia.

After Trump cancelled his planned news conference to refute the charges levelled against him in Georgia, Chris Christie said Trump’s silence is a sign the former president is scared of going to jail.

Broke and in serious legal trouble, Rudy Giuliani keeps asking his client, Donald Trump, when he might get around to paying him the presumably millions he owes Giuliani in legal bills. So far, nothing from Trump. Not I imagine the way an alleged felon would want to treat a co-conspirator and witness to the crimes he’s been accused of.

Thomas Beaumont and Hannah Fingerhut of AP talked to Republican voters at the Iowa State Fair about their thoughts regarding Trump.

By Jonathan Chait of New York: “‘Lock Them Up’ is Now the Republican Party’s Highest Goal” (“It is a strange twist of fate that years of hysterically accusing every leading Democrat of criminality culminated in Republicans falling behind a presidential candidate who came to politics from the world of crime. For some Republicans, the ascension of a transparently amoral swindler precipitated a psychic break from their party. But for most of them, it served merely to deepen the belief system they already subscribed to. Trump’s campaign and presidency followed directly from a mentality that detached the notion of criminality from any actual behavior and turned it into a partisan identity. Trump’s mantra — ‘The crimes are being committed by the other side’ — has become a partywide doctrine. But this idea, which has tightened its grip on conservative minds over the last generation, is now the dominant theme of the campaign. Trump’s indictments have intensified their humiliation and created an insatiable demand for revenge. The party is no longer running on policy or even culture war. It is now consumed above all with turning the criminal-justice system into an instrument of revenge.”)

A new report by the Housing and Urban Development Inspector General found the Trump administration withheld $20 billion in congressional disaster relief funds designated for Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in 2017.

By Glenn Kessler of the Washington Post: “How Republicans Overhype the Findings of Their Hunter Biden Probe”

Should Democratic Senator Dianne Feinstein really be representing the people of California in the Senate when she can’t represent herself in court?

In a groundbreaking case, the Montana Supreme Court ruled in favor of a group of young people between the ages of 5 and 22 who sued the state for violating their right to a “clean and healthful environment” by promoting the use of fossil fuels.

The Mason City, Iowa, school board is using AI to compile a list of books that would run afoul of Iowa’s new law prohibiting “age-inappropriate” and sexually-explicit books from school libraries. The list includes The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, Beloved by Toni Morrison, Looking for Alaska by John Green, The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie, An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser, The Color Purple by Alice Walker, Friday Night Lights by Buzz Bissinger, and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou.

Laura Meckler of the Washington Post reports on the boom in home-schooling.

Danielle Paquette of the Washington Post looks at the unsettling paranoia driving sales of home security systems.

Remember that time when Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen was served some psychedelic mushrooms in China?

Loveday Morris and Kate Brady of the Washington Post write that Germany’s far-right AfD Party is growing more popular and more extreme.

I claim the film rights to this article: “‘One Big Adventure’: The Russian Minister Who Fled the Draft to Drive Trucks in the US” (The story of how a Russian agricultural minister who ran afoul of his bosses and objected to the war in Ukraine fled his homeland, sought asylum in the US after crossing the Mexican border by foot, and got a job driving trucks across the United States. I’d cast 2003 Tom Hanks in the lead role.)

Vincent’s Picks: “Asteroid City”

I suppose this review contains spoilers, but if you’re watching Asteroid City for the plot, you’re missing the point.

About midway through Wes Anderson’s latest film Asteroid City (released in theaters this past June, now streaming on Peacock) an alien appears. This is unusual because Asteroid City—one of the year’s best movies—is not the sort of film in which an alien should appear. Yet there it is, descending from a flying saucer to swipe the town’s namesake meteorite as though it is retrieving an errant baseball from a neighbor’s flower garden without getting caught. How would you expect the characters of this film to react to such an incident?

That’s where it gets kind of tricky, because the characters in Asteroid City know they are just that: Characters. That’s because we as viewers know we’re watching a filmed production of a stage play called Asteroid City, as we are periodically shown behind-the-scenes black-and-white footage detailing the making-of the stage play Asteroid City. That documentary (which itself also has to be staged) is hosted by a Rod Serling-type narrator (Bryan Cranston) and airing on television sometime in the 1950s. If that isn’t confusing enough, at one point the narrator accidentally appears in the film version of the play. At another point, the play’s main character Augie Steenbeck, a recently widowed war photojournalist played by Jason Schwartzman, steps out of the play and into the black-and-white backstage area where, as actor Jones Hall, he asks the play’s director (Adrien Brody) if he is playing his role right since he doesn’t understand the play.

It is certainly tempting to interpret Asteroid City as a commentary on Wes Anderson films, as Anderson has a reputation as a rather inscrutable director. His films—which include Rushmore (1998), The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), The Aquatic Life of Steve Zissou (2004), Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009), Moonrise Kingdom (2012), The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), and The French Dispatch (2021)—are highly stylized works of cinema featuring meticulous scenic composition, stagey cinematography, and highly mannered acting. The formality of his work, structured in a way that is more sublime than rigid (but still dusted with irony) has a European aesthetic film school students may drool over but that likely weirds-out general American audiences. As funny and delightful as his films may be, though, it is understandable why some critics feel Anderson prioritizes style over substance, sacrificing meaning for mise en scene.

While Anderson seemed to use his signature style of filmmaking earlier in his career for more whimsical ends, over the past decade, he’s put that style to work in service to his movies’ ideas. It’s notable Asteroid City is the most American film Anderson, a native of Texas, has made. Set in the desert southwest, the film’s landscape looks like the background of a Chuck Jones cartoon. (If that isn’t obvious enough, a roadrunner makes a couple of appearances.) Its characters are costumed as post-war southern Californians. The Space Race looms over the action. The play Asteroid City is written by legendary playwright Conrad Earp (Edward Norton), a native of “upper Wyoming.” There are cowboys, one of whom is named Montana. Tom Hanks plays a grandfather.

There’s also an atomic bomb. Asteroid City is located near a nuclear test range, so the town’s residents have gotten used to the occasional earthshaking explosions. Augie snaps a picture of a mushroom cloud rising over the horizon. He also takes pictures of the despondent movie star (Scarlett Johansson) who is staying in the hotel room across from him. As a war photojournalist, it’s been his job to find and photograph scenes of death and destruction. He’s carrying the ashes of his recently deceased wife.

Yet Augie never cracks. Even after the alien visits the town, he and nearly every other character in the film maintain their composure. Could it be that we as Americans have become inured to craziness, to tragedy, to the extraordinary, to the devastating? These sort of things are not supposed to be everyday occurrences, but maybe we’ve come to treat them as such, just as the residents of Asteroid City—where for over 5,000 years, the biggest event in the town’s history was the day a rock fell from the sky—barely bat an eye at the daily appearance of a cop firing away at a getaway car as they speed through town. When Anderson’s characters do flinch—when they let slip the barest hint of pain, longing, or befuddlement—it can be crushing. There is something deeper there eating away at these Americans. That’s particularly evident when Jones steps away from the play and converses with the actress who would have played his wife in a flashback (Margot Robbie). She relates how that cut scene would have explained his character’s anguish. It might also allow Jones to deal with his own buried grief.

“You can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep,” Jones declares near the end of the film. Some have argued this asserts we still need to dream. I’m not sure the film supports that interpretation, though. I’d argue instead that it’s an argument for the importance of normal, unspectacular, everyday life, for being able to go about our days for weeks on end without the appearance of the traumatic so that we don’t become anesthetized to it. We don’t want to reach the point where nothing is shocking. We need to be able to experience the extraordinary as something more than ordinary, to be outraged by the outrageous, to mourn devastating loss, to be amazed by the truly amazing, to gaze upon an alien with wonder and awe rather than as just another typical Saturday night happening in Asteroid City.

Exit Music: “Nothing Compares 2 U” by Sinéad O’Connor (1990, I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got)

By O’Connor superfan Amanda Palmer: “This is a woman who ripped up a picture of the pope on Saturday Night Live (when it had no ‘safety delay’) to draw attention to the sex abuse happening in the Catholic Church, after delivering ‘War’ by Bob Marley, a cappella[.] Twelve days later she took the stage at Madison Square Garden for a Bob Dylan tribute festival and you could barely hear her sing over the boos and jeers from the crowd. She scrapped her planned Dylan song and screamed out ‘War’ again, as the crowd tried to overpower her.

That feeling. Many women have been there. I have been there too, shaking, as it feels like the whole world is trying to shout and drown you out, and put you in your place. Wondering if I am the crazy one. Wondering if this many people are right. Or wrong. Or even real.

She was right about the church. She was very fucking right.

She was right about so many things.

Now that she is dead, I know she’ll be lauded and applauded.

But back then? That night? How do you imagine she felt that night, crawling into bed, having been abused by a crowd of thousands? How would you feel? What would that do to you? Would you care if the world turned around, forty years later, and said: ‘Sorry about that, you were actually very brave?’…

She was hated, she was scorned, she was cancelled for being honest over and over again. That SNL move was the beginning of the end of a career in many ways. She never recovered.

Too much, they said. Go away.

She used her voice. She kept on speaking.

She was loud. Being a loud woman is not fucking convenient, for anyone. Ever. Not around here….

What the world did to Sinéad was death by a thousand cuts. The world lauded her, worshipped her, bought her, sold her, forgave her, claimed her, disavowed her. Over and over in cycles. How could anyone survive that? Like a piece of metal getting bent over and over and over again. It breaks.

She began as a fragile person. A fragile artist. Which is why her songs were so beautiful and powerful to begin with. A raw heart. A mother. Not an idea, not a theoretical. A person.

The world loved the taste of her. The world didn’t know how to digest her. The world spit her out.

She never apologized for ripping up that picture of the pope. When asked later, she said ‘I’m not sorry I did it. It was brilliant’.

It was.

She was.

Never forget this woman.

Let her memory guide us.

Let them scream at you, but do not stop singing.

Never apologize just to make them happy, to make them go away, to ‘get along’, to make them accept you.

No, no, no.

Me say War.

Sinéad….rest in world-changing ripped paper phoenix-pieces from the stage, rising and burning into the white night stars. Find peace at last. I hope you forgive us what we could not give you.