What Would It Take to Restore Americans' Faith in Democracy?

PLUS: A review of "I Told Them..." by Burna Boy

Regular readers of this newsletter know where I stand on the 2024 elections: Vote Democratic, because while Donald Trump and his Republican enablers pose an existential threat to American democracy, Joe Biden and the Democrats do not. It’s that simple. Understanding that rationale means you took the lesson taught to you on your first day of high school government class to heart: You are enrolled in this course because you will soon share responsibility for taking care of our democracy, which may at times involve recognizing and defending it from those who would subvert it. While democracy can be frustrating when you don’t get your way, it is of the utmost importance to protect it as a matter of principle, since democracy allows us to resolve conflict peacefully and is the form of government that best secures everyone’s freedom and equality, including your own.

I think that’s reason enough to vote Democratic in 2024. When democracy is on the ballot, you support it, even when you’re frustrated by it or if it means voting for a pro-democracy candidate who doesn’t share your political views. Doing so requires taking the long view: Let democracy slip away today and we may never get it back in our lifetimes, and we’d sure miss it when it’s gone. It’s what a good citizen does.

But what if many Americans don’t buy into that?

I’m not thinking here about those who are already predisposed to autocracy and authoritarianism. Nor do I have on my mind those who have grown jaded to democracy because they believe it fails to live up to the principles it espouses; despite their disillusionment, these people at least believe their flawed democracy should be better at being a democracy.

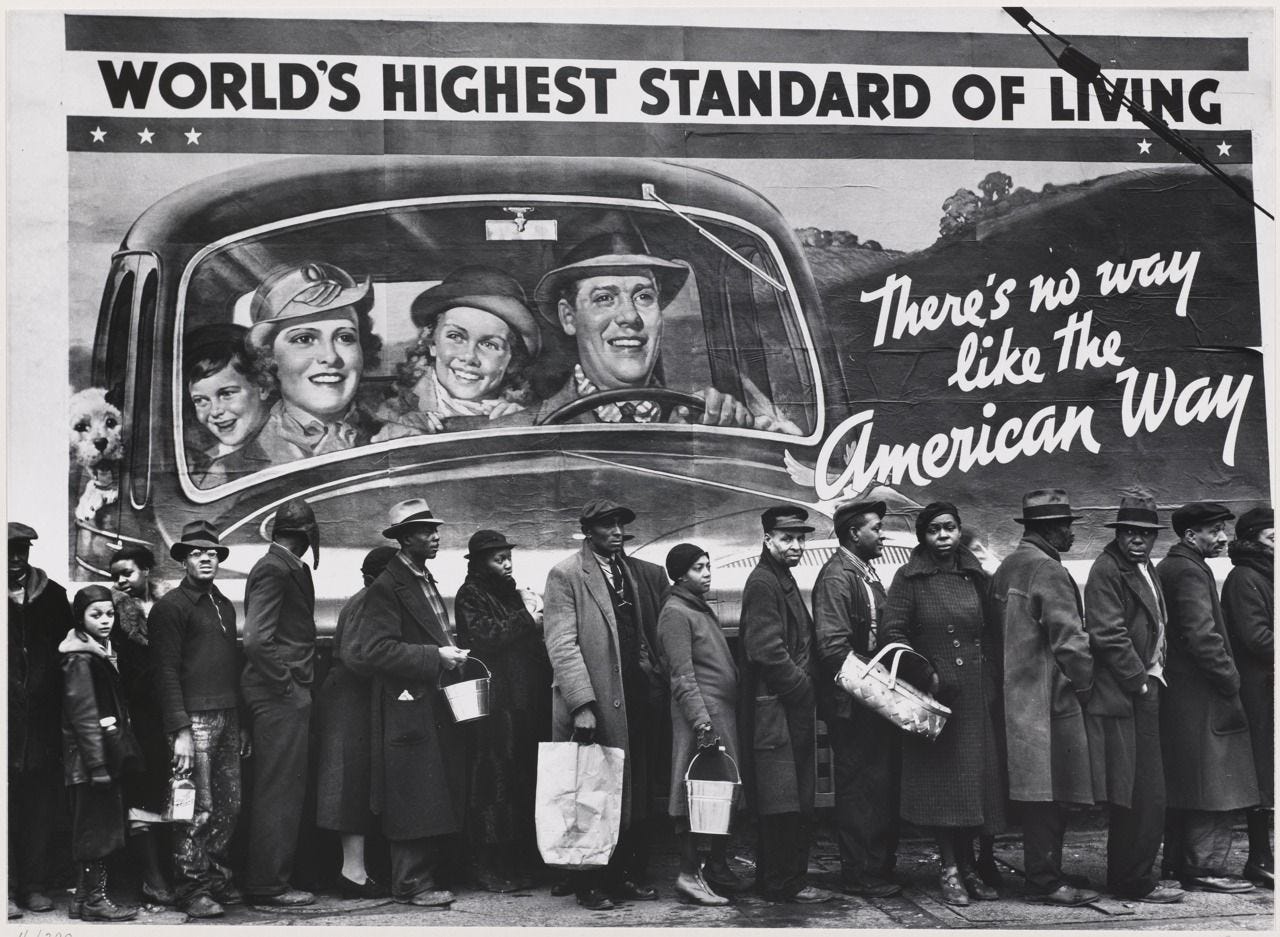

Instead, I’m thinking about those who have concluded democracy just doesn’t deliver the goods, that despite all the great things people say about it, their lives and the lives of most others are no better because of it. It may not be that these people are in some sort of economic or social distress themselves (although that may be the case) but that they see signs of distress all around them. Looking backward and then forward in time, they may conclude things just aren’t getting better, that no one is really addressing the underlying problems that have sent us on this downward trajectory. Democracy begins to look like an empty promise, no better or worse than any other form of government at serving the people. Consequently, when someone urges them to go to the ballot box to save democracy from the vandals, not only may they not bother, but they may give the vandals a second look, having concluded the champions of the democratic regime have done little to earn their loyalty and support.

Samuel Moyn, a law and history professor at Yale University, argues that is what is happening in the United States in his new book Liberalism Against Itself: Cold War Intellectuals and the Making of Our Times. As you can tell by that subtitle, Moyn thinks this situation has been brewing for some time but that we’re only now dealing with its most dire consequences.

Moyn is a liberal’s liberal who traces his perfectionist, progressive political thought through the Enlightenment, Rousseau, Romanticism, Hegel, and socialism. To put it another way, he believes in the human capacity for self-governance and social improvement, and that the highest form of liberty is a matter of self-discovery and self-creation. For Moyn, liberalism is an emancipatory, optimistic, future-oriented creed.

Moyn’s antagonists are the Cold War liberals, a group of intellectuals who rose to prominence during World War II and the early years of the Cold War. Moyn argues these thinkers—most notably Isaiah Berlin, Karl Popper, Gertrude Himmelfarb, Hannah Arendt, and Lionel Trilling—broke decisively with the liberal tradition they inherited. (He also focuses on Judith Shklar, whom he positions as a contemporaneous counter to those listed above.) In the minds of the Cold War liberals, both the fascism of Nazi Germany and the communism of Stalin’s Soviet Union—two very different systems of political thought that the Cold War liberals classified together as “totalitarianism”—had their roots in the Enlightenment. The fascists and communists took the Enlightenment’s faith in reason, mankind’s potential for evolution, and the perfectibility of the world to their disastrous conclusions, and by claiming they were following a path prescribed by the discernable laws of history, they justified their actions as inevitable and necessary. Liberals should have learned their lesson when the 18th century’s French Revolution, the crowning social experiment of the Enlightenment, turned into the Terror. Instead, they pressed ahead with their belief that the state could engineer society, leading in the 20th century to the carnage of the Second World War, the Holocaust, and the rise of a Soviet army that threatened to subjugate Europe.

The Cold War liberals did not offer a more measured version of liberalism (say, democratic socialism) as a counter to communism. Even the liberal New Deal seemed to flirt with danger. Instead, feeling besieged by the threat of communism and terrified by both the power of the modern state and the dark impulses lurking within the hearts of men, Cold War liberals backed limited government, laissez faire capitalism, and social institutions that preached self-control. Along these lines, Berlin famously popularized the distinction between “negative liberty” (freedom from restraint) and “positive liberty” (the freedom to act) and argued that efforts to ensure citizens have the freedom to act—particularly when undertaken by the government—went too far. It was better to leave people alone than create government agencies that might ultimately oppress them. The result was a form of liberalism that, according to Moyn, owed less to the liberal tradition than it did to conservative critiques of liberalism.

While it is true Cold War liberalism did not try to roll back the New Deal, it certainly did not advocate for its expansion. The New Left turned “Cold War liberal” into an epithet in the 1960s, but the philosophy came back into vogue in the 1970s when free market neoliberals and hawkish neoconservatives looked to it as foundational to their own political thought. By the time the Cold War ended, it had not only been rehabilitated but positioned as the supreme version of liberalism.

Moyn argues that has turned out to be a massive problem. Cold War liberalism—which leaves people to their own devices and keeps government out of their lives—has struggled to respond to the challenges posed by globalization, automation, deindustrialization, and the rise of the Internet. Those conditioned by Cold War liberalism to regard the government as a dangerous nuisance tend to blame the government for creating those problems, while those who expect the government to step in are disappointed it hasn’t done more. Many can’t even imagine how the government might intervene to address these issues. More seriously, however, when Donald Trump emerged as a threat to the United States’ liberal order by promising voters he would serve their interests as a strongman, liberals on both the Left and Right had little to offer beyond the defense of a liberal status quo few felt was worth defending. For the descendants of America’s Cold War liberals, Trump seemed to come out of the blue for reasons they didn’t understand. Furthermore, they lacked the intellectual framework and imagination needed to confront and successfully resolve the crisis.

Moyn’s argument isn’t exactly new, but his excavation of the political thought of the 1940s and 1950s shows how liberals turned their backs on the intellectual legacy of the New Deal. With that said, I can’t recommend the book to you unless you’re someone who’s interested in histories of intellectual history, and even then you may find this a slog. Moyn’s book reads like a series of lectures delivered at a political theory conference to an audience immersed in this material for years and harboring a serious grudge against Isaiah Berlin. It takes time to unpack the implications of sentences laden with ambiguity. This isn’t a book for novices.

But even taking it as an academic work, Liberalism Against Itself will earn its critics. Moyn gets so caught up describing who was writing what and influencing whom (at times he chronicles which books these thinkers had in their personal libraries and if they were annotated) that he loses sight of the big ideas he ought to be pinning down. He also spends so much time accounting for counterarguments and his subjects’ subtle shifts in emphasis that one eventually ends up wondering if we’re getting a complete portrait of Cold War liberalism or merely peering at it through the lens Moyn prefers. Having read a lot of Hannah Arendt, I know Moyn correctly calls her out for the weaknesses in her argument, but he also glosses over a lot that would recommend her to liberals, particularly her emphasis on political novelty.

Additionally, Moyn plays a little lose with the word “liberalism.” At times, liberalism is the philosophical heritage of the Enlightenment; at other times, it’s more akin to New Deal-style Left-wing politics. Yet when he references contemporary liberalism, he’s thinking less about Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez than he is center-right politicians like Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, and George W. Bush or “end of history” intellectuals like Francis Fukuyama. Even though he admits there are many liberal alternatives to Cold War liberalism, Moyn seems to insist its true natural progression runs from the Enlightenment through Rousseau to European-style democratic socialism. Positioning Cold War liberalism as a “betrayal” of the liberal tradition, he plays up its debt to conservative Edmund Burke but not John Locke, whom I would pinpoint as the originator of liberal political thought. Consequently, Moyn seems more interested in disqualifying Cold War liberalism as “liberalism” (however it should be defined) than countering it.

Moyn would have been better off organizing Liberalism Against Itself around its major ideas than his subjects (which turns his book into a prolonged “Look at where these buffoons went wrong!” expose.) All of which reveals his book’s biggest flaw, which is that for all its talk for the need of an alternative to Cold War liberalism, it never provides us with one. The crumbs are there: Moyn would have us alter our assumptions about the world so that we put more faith in the goodness of citizens, actively work to discern where the future is leading society, and enlist government as the agent that can navigate that transition to the new world. As Moyn says, that will require imagination, but he’s so preoccupied with cataloging the errors of Cold War liberalism that he neglects to posit an alternative.

That’s a serious project, and Moyn’s book is valuable if it prompts readers to question their assumptions about liberalism and begin formulating new models of liberal politics. I suspect Moyn would have us assemble a multiracial coalition of voters united along class lines, but that ignores just how much people’s views of the economy and the government’s involvement in it is knotted up with race. It seems we’re less divided these days over economic policy than we are over who ought to wield power and to who’s benefit. Others—including (increasingly) myself—might argue we need to overhaul the political system to make it more democratic and responsive to the challenges we face today, but I worry that procedural solution may not be enough to satisfy people’s material demands. I’d also be concerned how a populace sour to the very idea of government might redesign it (I guess that’s my inner Cold War liberal speaking.)

But liberals, Democrats, Leftists, progressives—whatever you want to call them—need to begin imagining a new liberal project, one that not only addresses the political and economic issues confronting the country but the cultural, psychological, and spiritual aspects of American life that rattle our politics. Instead of asking the people to defend a democracy that feels remote and unresponsive, ask them to support a democracy that makes an actual difference in their lives. Defending democracy on principle should be enough, but without a revitalized political project that reorients the nation toward the future rather than the past and that gets down to the heart of what has so many Americans on edge today, a critical portion of our population may conclude the democracy they’re being asked to stand up for isn’t worth saving.

Signals and Noise

By Jonathan Chait of New York: “Attacking Trump as ‘Unelectable’ is Just So Pathetic” (“The appeal of the electability argument, despite the absence of any solid evidence for it, is that it allows Trump skeptics to avoid making any moral case against Trump. It is probably a correct calculation that a party dominated by Trump admirers will not support a candidate who believes Trump has done anything worse than occasionally write a ‘mean tweet.’ But the single-minded focus on electability is not merely a communications strategy. It is also a way of establishing moral boundaries within the party. And the message sent by focusing on Trump’s electability is that the only problem with his behavior is that it reduces the party’s chances of obtaining power. If Trump does win the nomination, which now appears extremely likely, the electability argument leaves no room for abandoning him; to the contrary, it creates a permission structure for Trump skeptics to once again support him as the lesser evil.”)

Natalie Allison of Politico finds Republican presidential candidates aren’t talking about Hunter Biden because not only does it fall flat with GOP voters but plays right into the hands of Don Trump.

Tim Miller of The Bulwark looks at how useless SuperPACS are in today’s political environment. (“HERE’S THE REALITY: If the [DeSantis-aligned] Never Back Down PAC had spent every dime that has thus far gone to TV ads and canvassers on sculpting a giant golden idol alongside I-80 in central Iowa that depicts DeSantis kicking an immigrant child in the ass, there is no available evidence that their candidate would be worse off than he is today. Hell, he might even have gained a point or two with the MAGA base for such a lib-owning, Alpha maneuver.”)

Nate Cohn of the New York Times examines Biden’s declining support among minority voters. (A new CNN poll finds dismal numbers all around for Biden, who continues to run neck-and-neck with Trump.)

The chatter about whether Biden should stand for another term is building. A few samples:

“It’s Time for Biden to Leave the Stage” by Andrew Sullivan

“Hidin’ Biden” by Joe Klein

“Why Is Joe Biden So Unpopular?” by Ross Douthat of the New York Times

“Ageist Attacks Aren’t New in Presidential Campaigns, and They Haven’t Worked” by Bill Scher of Washington Monthly

A USA Today poll found Trump with a 32-13% lead over Biden among non-voters. Many such Trump-leaning voters won’t head to the polls because they believe the voting system is rigged against them. (It’s an interesting article if you’re interested in the rationale of people who choose not to vote.)

Brace yourself for a messy month on Capitol Hill as Congress (that’s not the right noun) tries (that’s not the right verb) to keep the government funded and open. But it looks like a bipartisan coalition in the Senate including Mitch McConnell is going to jam McCarthy’s House Republicans by passing the spending bills the House MAGA wing intends to ignore. Speaker McCarthy’s choice: Pass the Senate bills and face the fury of MAGA (who could then oust him as Speaker) or renege on his deal with Biden, let himself be taken hostage by the MAGA wing, ignore the bipartisan bill, and shut down the government.

Republican Rep. Matt Gaetz of Florida is threatening to force an impeachment vote if McCarthy doesn’t schedule one.

GOP senators were informed the term “pro-life” no longer plays well with voters.

Decca Muldowney of The Daily Beast reports Republicans are freaking out over masking again.

A federal court has ordered Alabama to once again redraw its congressional map. This past June, the Supreme Court struck down Alabama’s map, arguing it diluted the political power of Black residents and thus violated the Voting Rights Act. Alabama redrew its map but deliberately did not address the Supreme Court’s concerns. Alabama has seven congressional districts. Approximately 27% of the state’s population is Black and 66% white, but there is only one majority Black district. No district is electorally competitive.

Remember the Wisconsin Supreme Court election earlier this year that gave liberals a majority on the state court? With that majority poised to protect abortion rights and throw out the state’s heavily gerrymandered (and disproportionately Republican) legislative map, the Republican-led legislature is now poised to impeach and remove that newly-elected judge from the Court. And it looks like they have the votes to do so.

Ex-Proud Boys leader Enrique Tarrio, who organized the most violent gang that assaulted the Capitol on 1/6, was sentenced to 22 years in jail.

Trump White House aide Peter Navarro was found guilty of contempt of Congress for refusing to cooperate with the 1/6 committee.

Democratic Mayor Eric Adams asserted the city’s migrant crisis will “destroy” New York City. Jonathan Weisman and Nicholas Fandos of the New York Times write Texas Governor Greg Abbott has effectively nationalized the border crisis by busing migrants to northern Democratic-led cities.

Sheryl Gay Stolberg of the New York Times reports new abortion restrictions are causing obstetricians to flee red states, leading to what some worry may be a maternity care crisis.

Daniel K. Williams writes in The Atlantic that as more and more people quit attending church, they do not become more secular (and thus more liberal) but retain their political leanings.

Strong economic data has the Fed revising its economic growth forecast upward.

Politicians from Ronald Reagan to Barack Obama have been warning Americans for decades that Medicare spending threatens to blow up the federal budget. But, as Margot Sanger-Katz, Alicia Parlapiano and Josh Katz of the New York Times, found, Medicare spending per beneficiary has basically held steady for the past ten years (saving the U.S. government $3.9 trillion) and analysts aren’t sure why.

Yet the federal budget deficit is exploding this year at a rate usually seen during major national crises. This is happening despite steady economic growth.

Annie Gowen, Niko Kommenda, and Saiyna Bashir of the Washington Post look at the health risks that will accompany climate change.

Top 5 Records Music Review: I Told Them… by Burna Boy

I should let you know upfront I am no expert in African popular music. To even say I’ve dipped my toe into it is an overstatemnet. But I am here for Burna Boy.

Daniel Ogulu, aka Burna Boy, is a 32-year-old afrobeats musician from Nigeria. His most recent album I Told Them…, released near the end of August, has already topped the charts in the UK and cracked the top ten in five other European countries, but despite exposure in the hip-hop and R&B markets, it’s is still flying under the radar in the states. American audiences would be wise to familiarize themselves with Burna Boy’s work, though, as he seems to be lighting the way to pop music’s future.

It is almost obligatory in articles like this to distinguish Afrobeat (a blend of Yoruba music and highlife influenced by funk and jazz that developed in Nigeria in the 1960s and 1970s and was popularized by Fela Kuti) from afrobeats (a catch-all term for twenty-first century pop music originating in West Africa and its diaspora, with production centered in Lagos, Accra, and London.) While afrobeats has struggled to gain traction in the American market, it’s been a major influence on the work of Drake (“One Dance” is the most notable example) and Beyoncé drew on the style when recording The Lion King: The Gift. Over the past five years, though, afrobeats artists themselves have started to gain prominence here. This year’s NBA all-star game halftime show featured afrobeats performers exclusively, including Burna Boy. Over the summer, Burna Boy became the first African artist to play 40,000+ and 60,000+ stadiums in the US and UK respectively.

As you may have surmised, Burna Boy is not only the world’s biggest afrobeats star, but also the performer most likely to breakthrough in America. His sound is a fusion of West Africa, the Caribbean, and cosmopolitan England. There’s almost always a polyrhythmic jùjú beat propelling his songs, but it never overwhelms his compositions. Instead, Burna Boy’s vocals—often plaintive, seemingly elongated with auto-tune—seem to slow down time. It creates a woozy, wobbly effect, as though we’re catching him in more than one place (or continent) at that moment. Neither too hot nor too chill, Burna Boy’s music simmers and sizzles, the output of an artist breaking a sweat but never straining.

The element of Burna Boy’s work most likely to connect with American audiences is its debt to R&B and rap. I Told Them… features guest appearances by members of Wu-Tang Clan. Trap beats skitter through his songs. The pristine, aspirational vibe of many tracks places him in the company of Chicago artists like Chance the Rapper. On “Sittin’ On Top of the World”, he even samples Brandy, drawing an unexpected but effortless connection between West Africa music and 90s R&B slow jams.

Despite songs like “Cheat On Me”, which condemns the racism and hostility directed toward African immigrants in the UK, I Told Them… is a less overtly political album than previous records like African Giant (2019). (In fact, if you’re interested in exploring Burna Boy’s catalog, I’d recommend starting there.) Still, Burna Boy’s Pan-African political vision permeates his work. Some have suggested afrobeats waters down its African heritage by fusing it with sounds that appeal to homogenized western tastes. That misses what Burna Boy is trying to accomplish with his music, though. Notice how Burna Boy sometimes seems to be singing from a distance in his songs, even when boasting, a bit hoarse and muffled, as if beckoning the listener to come find him. That’s the sound of an artist actively creating a new space, a new audience, even a new nation out there in the Transatlantic world he traverses. Unable to pin his location down, we keep searching for Burna Boy regardless.