The Biden Presidency After One Year

PLUS: An Australian Open...oh, never mind, let's talk about Novak Djokovic

It’s a year into Joe Biden’s presidency, and everyone’s writing its postmortem.

And as soon as those post-mortems are published, others are just as quick to remind everyone the midterms are still a long ten months away and the presidential election even further out and a lot can happen between now and then in this highly unpredictable political environment.

And it’s not hard to imagine a scenario in which the pandemic fizzles out this spring, restrictions get lifted, people get out and about again, the economy starts humming, Biden’s approval rating recovers, and Trump’s presence in the 2022 campaign sabotages his party’s chance to regain control of Congress.

But then again, even if the pandemic does just sort of go away, voters might also be ready to cast aside the party that pledged to manage it (and struggled to manage Omicron.) Free of government restrictions, they may not want much to do with the party most closely identified with government interventions, either. It may take another year to straighten out the economy. If inflation does subside, sticker shock may remain. Democratic voters may be demoralized by their own party’s inability to enact a broader Democratic agenda. A resurgent Trump may lead Republicans to victory in the midterms, and then we end up with two years of political gridlock, government shutdowns, pointless congressional investigations, debt ceiling showdowns, rule by executive order, and either presidential primary drama or the longest presidential campaign in American history.

There are other variables, of course. Maybe another variant pops up. Who knows what Vladimir Putin or Xi Jinping have up their sleeves. The demise of Roe v. Wade could energize pro-choice voters. The 1/6 committee might find a smoking gun or nothing new at all. And those are only the foreseeable unpredictables.

But come on, they’ve been remaking this midterm movie for decades.

A year into his presidency, Biden finds himself in a tight spot. He had a good first six months; the last six months have been rough. His management of the United States’ withdrawal from Afghanistan was not good. A resurgent pandemic and the economic turmoil it continues to wreak have been a major drag, and his administration’s response to both has been flat-footed and often muddled.

But let’s focus today on Biden’s legislative agenda, which is the means by which a president delivers on the vision of the country he pitched to voters. Biden had major wins early on: A big relief package and the infrastructure bill. Those are no small achievements, and it wouldn’t hurt for Democrats to talk about them more. But his Build Back Better plan, packed with new social spending and measures to address climate change, is stalled (perhaps permanently) and his voting rights bill is doomed. Other priorities like the DREAM Act and a minimum wage hike have languished all year. Much of his legislative agenda remains unfulfilled, and voters know this. How, then, should we assess Biden’s legislative record, particularly when it comes to Build Back Better, the heart of his legislative ambitions?

Some argue Biden overreached from the start, that his agenda was far too ambitious given the political realities of the country. What was it Mitt Romney said on Meet the Press this past Sunday? “He’s got to recognize that when he was elected, people were not looking for him to transform America. They were looking to get back to normal. To stop the crazy. And it seems like we’re continuing to see the kinds of policy and promotions that are not accepted by the American people.”

Romney might have a good read on that. It could be the American people more than anything else simply wanted Trump out, a steady hand to guide the ship of state, and nothing more; basically, an interim presidency. And the congressional majorities Biden ended up with—most notably a 50-50 Senate—certainly suggested an extremely limited legislative way forward even with bipartisanship on the table. I kind of always have to remind myself of that: Anything Congress did pass was going to be a minor miracle, since Biden would have about as much power to enact his agenda legislatively as the grand marshal of the Rose Parade.

But Biden had to stand for something. As Hillary Clinton learned in 2016, he couldn’t simply run as “Not Trump,” as both his base and middle-of-the-road voters expected more from him than that. And contrary to what Romney claimed, the policies Biden ended up standing for were actually quite popular. For example, he famously rejected the Medicare for All plan pushed by Bernie Sanders during the primary in favor of making more modest reforms to Obamacare. Build Back Better is built around policies that poll well with the American people.

The other issue that confronted Biden was that the Republican Party had delegitimized itself as a governing institution by embracing Trump. Any doubt that was the case was erased on January 6, 2021, and certified when so many Republicans refused to impeach and remove/bar Trump from office. No matter the merits of conservatism, politicized conservatism in the form of Republicanism threatened to undermine American democracy. (When Romney says Biden was elected to “stop the crazy,” Romney should be asked why he caucuses with and would vote to empower the crazy.) Once Biden took office, it was abundantly clear Biden couldn’t just serve as a seat-warmer who put nothing but time between Trump and whatever candidate an unrehabilitated Republican Party ran for president in the near future. It was imperative for the future of American democracy for both Biden and the Democratic Party—the only major American party serious about both governance and democracy—to succeed politically, and the way to do that was by proving to the working- and middle-class voters who had drifted from the party in 2016 and 2020 that the Democrats could not only make the government work but that they could disrupt it enough to make it work for the average American rather than the rich and powerful.

An aside: It is worth pondering the possibility that the Democratic focus on economic discontent does not really address the core grievance of many of the economically discontent voters Democrats are trying to win over. A populist economic message certainly has the potential to bring disillusioned Democrats and Democratic-leaners back into the fold; at least that’s what Bernie Sanders thinks. Many also argue policies like free community college, paid leave, universal pre-K, and lower prescription drug prices can unite Americans of diverse backgrounds around a materially beneficial agenda. But what if that approach actually has the opposite effect? Perhaps after eight years of an Obama presidency and the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, many White Americans—including many who had voted for Democrats in the past—grew hypersensitive to government interventions on the assumption that the government had become too responsive to the demands of the Black community and that the benefits of the government’s interventions (no matter how popular those interventions are) would flow disproportionately to “undeserving” Black Americans. If that was the case, because the root of many White Americans’ economic discontent is grounded in racial resentment (which Trump weaponized) and because Democrats are so closely affiliated with Black voters, many White Americans may end up rejecting populist Democratic economic and social proposals out of hand. How Democrats confront this dilemma without rejecting their commitment to racial progress may be the key to their future success. (I’ll develop this idea more in a future article after I’ve given it some more thought.)

That aside aside, however, Democrats concluded the way forward was passing an ambitious domestic agenda aimed at working- and middle-class Americans that involved massive new spending on public works, climate change countermeasures, and social programs. If voters rewarded them for their efforts, their success would be democracy’s success. After Republican state legislatures began passing restrictive voting laws in response to Trump’s claim that the 2020 election was stolen from him, Democrats incorporated voting rights legislation into their agenda. With narrow congressional margins and a Republican Party that experience told them they could not trust, it was going to be a heavy legislative lift. Democrats had one hope: That a spirit of party unity would prevail in this perilous time.

It almost did.

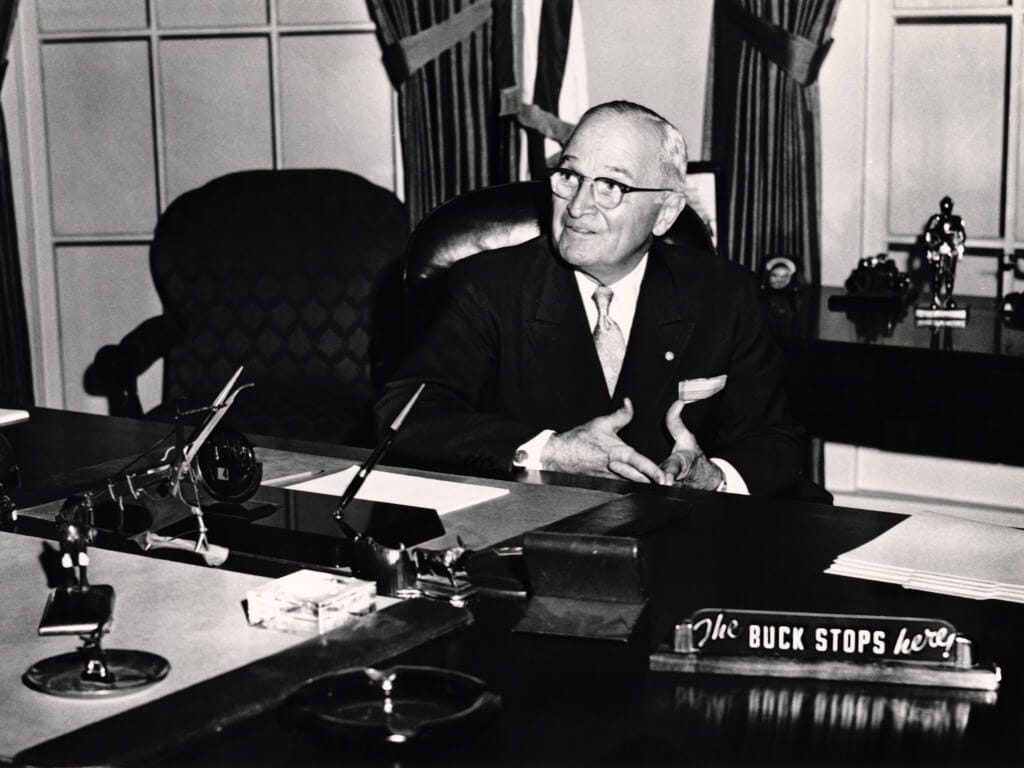

“The buck stops here.” For most Americans, it’s an accepted truth of American politics. At the end of the day, it’s the president who’s responsible for how well the government functions. Yet the president is also a captive of political conditions and shares power with co-equal branches of government. When it comes to passing a legislative agenda, successful presidents don’t just will bills into law. They benefit from circumstances and cushioned majorities.

Does that absolve Biden for his failure so far to enact his Build Back Better plan? (I say “so far” because I still think it’s likely he’ll end up signing some aspect of that legislation into law.) If presidents are judged by results, it’s fair to say he miscal-culated when trying to cobble together a majority. Maybe he was working with the wrong legislators or the wrong piece of legislation or defined success the wrong way. Would those alternatives have met the needs of the political moment, though? Maybe. Maybe they would have only amounted to half-measures, too. The power of the president is the power to persuade, so maybe Biden has yet to land on the particular argument that would have won him a majority. Given the circumstances, though—the makeup of Congress, the state of the nation—I think he played his hand about as best as he could. Problem was he was dealt a Manchin and a Sinema.

What to make of these two? Manchin obviously has to account for the politics of a very conservative state. He’s also fundamentally conservative by nature, both culturally and in his views of government. That helps explain why he’s perfectly fine with voting against bills. But I don’t think his political disposition completely explains his behavior. For instance, after the Sandy Hook school shooting, he got on the wrong side of the NRA by co-authoring new gun control legislation. And it isn’t as though he isn’t open to a lot of Build Back Better’s provisions, specifically $1.5-1.8 trillions worth of it. Weirdly, the portions of the bill that are pretty much settled are the climate change provisions, which would presumably be the biggest sticking point given that Manchin calls West Virginia home. I would think there would be a way for Manchin to get himself to yes.

My new theory about Manchin is that the ideological content of the bill ultimately doesn’t matter all that much to him. Democrats have moved and are willing to move pretty far to accommodate those concerns, particularly when it comes to the bill’s price tag. There’s also the irony that Democrats from closely-contested districts in the House continue to push for its passage, proving Build Back Better’s political appeal extends far beyond its loudest progressive supporters. What matters more to Manchin is that he wants to be the architect of the bill. In his heart, Manchin fancies himself a-wheeler-and-a-dealer. Unlike Bernie Sanders, whose service in the Senate is motivated by ideology, Manchin is there because that’s where the action is, and he wants to play the role of lead negotiator. If he isn’t playing that role, he’s not happy. Without his input and guidance, any bill—even one designed with him in mind—is by definition a bad bill. He’s not a rubber stamp, he does not merely want to be consulted, he does not want to tinker at the margins of legislation, he does not want to be told to get in line, he does not want someone else dictating the terms to him. He wants to go into a smoke-filled room and negotiate with someone else what gets included in his bill. Manchin’s not someone to be bargained with; he is the bargainer-in-chief. Not only does it fit his brand back home—at the end of the day, he can tell his constituents he never let Washington roll him because he personally vetted every aspect of the bill—but it also stokes his ego.

Sinema is a somewhat different story. She is not your typical freshman senator. A one-time member of the Green Party, Sinema started her political career in the Arizona legislature as a progressive but developed a reputation as someone quick to cut deals with Republicans. Some suggest her independent streak mirrors Arizona’s status as a newly competitive battleground state, but unlike Sinema’s slide from liberal to conservative, Arizona’s politics appear to be sliding in the other direction. But then again, ideology doesn’t seem to matter much to Sinema. She constantly reminds people in her public statements that she deplores partisanship while insisting cooperation and compromise are the only way forward. A self-styled maverick a la John McCain, Sinema follows the beat of her own drum and expects others to accept her rhythm. She has no reputation as a team player; her relationships are purely transactional. No one doubts her smarts or political instincts, even as she alienates many Arizona Democrats. More than anything else, she is said to be driven by her own ambition and high estimation of her own talent (not unusual among senators, but in ample supply in Sinema’s case.)

There have been rumors Sinema will become a Republican if the GOP gains the Senate majority in 2022. I doubt that, as it would be political suicide. My guess—a wild one, at that—is she eventually drops her party affiliation all together, maybe caucuses with the Republicans if they’re in the majority, and then runs for president in 2024 as a groundbreaking independent and self-styled national savior who promises to split the difference between two parties she would characterize as too extreme. Build Back Better is the vehicle she is using to burnish those credentials.

(For more on Sinema, read these profiles in The Daily Beast, the Alex Pareene Newsletter, Politico, and The New Yorker.)

At the end of the day, Sinema is easier to win over: She needs to be seen as a dealmaker, which requires her to actually make a deal. Manchin, on the other hand, can take or leave almost any piece of legislation. So absent a new-found sense of party unity and the Manchin roadblock, does Biden’s agenda have a legislative way forward in Year 2? Some options:

1.) Leave Build Back Better for dead and just take a couple easier wins, like the bill that would target Chinese microchip manufacturers by boosting domestic production of semiconductors or another that would prohibit members of Congress from buying or selling stocks.

2.) Pare Build Back Better way back to what Manchin is already on record as supporting, pass it quickly (maybe by the State of the Union) and move on.

3.) Put Manchin himself in charge of designing a new Build Back Better bill.

4.) Peel off pieces of the bill (i.e., the now-expired Child Tax Credit,) find enough Republicans to go along with each bill, and try to pass them individually through regular order rather than reconciliation.

5.) Load Build Back Better up with so much pork aimed at West Virginia and Arizona that Manchin and Sinema would have no choice but to vote for the bill.

I suspect we’ll end up with some combination of 2.) and 3.). Although the bill will contain a lot of positive elements, progressives will be disappointed they didn’t get more, which will lead Manchin to look down upon them as the self-appointed adult-in-the-room and declare, “You get what you get and no complaining.” As for voting rights, which was voted down last night in the Senate by a vote of (get this math) 51 in favor and 49 against: Appeal as much as you want to her conscience, but Sinema simply believes the minority’s right to stop legislation in the Senate matters more to democracy than the voting rights of citizens.

Say what you will about the buck stopping with Joe Biden, but here’s a truth: In this political moment, the buck stops with Joe Manchin, too, and Americans should regard him accordingly. Maybe there’s a way around Manchin involving some sort of coalition with Republican senators Lisa Murkowski, Susan Collins, and Mitt Romney, but my guess is if it got to that point, Manchin would be in the mix as well. Joe Manchin runs Congress. Joe Manchin is the legislative branch. It’s time to put him on the hook for the results.

Garbage Time: What’s the Deal With Novak Djokovic?

(Garbage Time theme song here)

The Australian Open started this week! You know what’s great about the Australian Open? It’s played in January. That means us Northern Hemispherians can turn on the TV, flip to whatever channel is showing the Aussie Open, and find ourselves immediately transported to a place where it is the middle of summer. It is so sunny there. It looks so warm. We’re given two weeks of that in the middle of freezing winter.

It’s kind of easy to pick a favorite this year on the women’s side of the bracket. Ash Barty is the #1 player in the world and she’s from Australia. Picking anyone else is just selecting at random. The catch, though, is that the draw has Barty lined up to play defending champion Naomi Osaka in the fourth round three days from now so long as both women win their matches tomorrow. That would be a tantalizing match.

As for the men, Daniil Medvedev is like playing a wall but come on you’re not here for the tennis analysis you’re here for the Novak Djokovic hot takes. As everyone in the world knows by now, Australia does not allow unvaccinated foreigners into their country, which seriously complicated the top-ranked Djokovic’s plans to play in the tournament since he remains unvaccinated. Djokovic, however, claimed he had recently contracted COVID, which was apparently the basis for a vaccine exemption granted to him by Tennis Australia and the local Victoria government. Still, upon arrival, he was detained by Australian border authorities as unvaccinated. Eventually a court ordered his release on procedural grounds but not before it was learned Djokovic hadn’t isolated himself after testing positive back in December; not only was that in violation of COVID protocols in his home nation of Serbia, but it also did not correspond with an answer he gave on his Australian travel entry form stating he had not traveled anywhere in the two weeks prior to his arrival in Australia. (Social media photos easily proved otherwise.) Djokovic attributed the mistake to “human error” on the part of his support team. Just a few days later, though, an Australian government official ordered Djokovic to leave the country, meaning the #1 men’s tennis player in the world would not be able to compete for a fourth consecutive Australian Open title nor record his twenty-first major victory, which would be a record. He now faces banishment from Australia for three years (most think that’s unlikely) and France has indicated his participation in the French Open this spring is up in the air as well.

I’ve written about Djokovic at length before so I won’t rehash those points. What’s worth noting is that this latest drama could derail his quest to become the most decorated men’s tennis champion of all-time. He was hoping to secure that record at the U.S. Open last fall but was defeated in straight sets in the final by Medvedev. At thirty-four years old, Djokovic certainly has a lot of tennis ahead of him, but he’s about to exit his prime just as Medvedev and much of the rest of the men’s field begin to enter theirs. No one would bet against Djokovic winning another title, but Father Time is only going to give him so many more chances. Meanwhile, Rafael Nadal—only a year older than Djokovic and tied with him and Roger Federer for all-time career major wins—has to be chomping at the bit. He’s dropped in the rankings to #6 and not quite the player he used to be, but he remains dangerous. A win in Australia would give him the record alone. Then he’d move on to Paris, where he’s dominated the French Open’s clay courts, winning 13 of the past 17 tournaments there. (Djokovic did defeat him in the semis last year.) A two-title lead at this stage in their careers might be too much for Djokovic to overcome.

The added kicker is that Djokovic, whom fans had never really taken a shining too, finally had people pulling for him before the Debacle Down Under. Last fall he had a New York crowd eager to see history made cheering him on, and he earned a lot of people’s sympathy when he broke down on court while awaiting the start of the trophy ceremony. Now he’s playing the heel. Whatever sort of goodwill he had in Melbourne—which had just endured a 200+ day lockdown—is significantly depleted.

The obvious question to ask is why Djokovic put himself in this situation. His refusal to get a vaccine doesn’t seem political, nor does it seem rooted in a sort of libertarian resistance to authority. Some have speculated he arrogantly assumed the rules don’t apply to a player of his stature and that Australia would never have denied entry to the world #1, but Djokovic has never struck me as the sort of person who leans on a sense of entitlement. He has exhibited a disregard for the danger posed by the virus and the danger his actions as an unvaccinated person pose to others: In the early months of the pandemic, he actually held a tennis event to lift the spirits of Serbia only to see it turn into a super-spreader event that left him and his wife infected, and last December he met with a reporter for an interview after he had tested positive for COVID. (It’s worth wondering if he actually did test positive in December 2021 or if, absent proof of vaccination, he merely claimed he did as a way to get around Australia’s regulations. No matter what, he seems entangled in a web of deceit and irresponsible behavior.)

The most convincing reason I’ve heard is that Djokovic is a kooky health nut aiming for an ultra-elite level of performance who does not want to introduce something like a vaccine to his body. I would think, however, that a health nut would also be very concerned about introducing something like COVID-19 to his body. In fact, his cavalier behavior during the pandemic suggests he doesn’t take the virus and its potential implications for his health seriously at all. Maybe he assumes the virus is something “natural” his highly-tuned body can cope with while the vaccine is something “unnatural” that should be avoided. It’s all very weird.

If Djokovic’s refusal to get a vaccine is related to his health and training regimen, the irony is that this particular choice is preventing him from using his elite-level health and training to win another Grand Slam title. What’s the point of training so hard and getting all this expert-level health advice if it keeps him from playing tennis? That makes it an odd principle to stand on. Just get the shot! It also makes me think it’s kind of a miracle Djokovic is in the shape he’s in if he’s taking health and medical advice from sources who are not recommending the vaccine.

But enough about Djokovic. There’s still a week and half left of the Australian Open. Take some time to enjoy the Victorian summer.

Exit music: “The Wire” by Haim (2013, Days Are Gone)