Rather Than Point Fingers at Each Other, Democrats Need to Strengthen Their Party

PLUS: A review of "Never Enough" by Turnstile

Zohran Mamdani’s victory in New York City’s Democratic mayoral primary has inspired a new round of bickering within Democratic circles about the future of their party. Mamdani is a thirty-three-year-old Muslim assemblyman from Queens affiliated with the Democratic Socialists of America. He ran for mayor on an affordability platform that includes proposals for fare-free busing, government-operated grocery stores, rent-freezes on apartment units, a $30 minimum wage, and tax hikes on high-income earners.

Mamdani wasn’t supposed to have a chance in a large field of higher-profile Democratic candidates, but his policy agenda, spirited campaign, and status as a party outsider made him the favorite of the left. Pundits assumed former New York Governor Andrew Cuomo—a center-left candidate with high name recognition—would win the ranked-choice primary despite his considerable baggage. (As governor, Cuomo concealed his mismanagement of the COVID pandemic and later resigned after at least eleven women accused him of sexual harassment.) Yet by election day, Mamdani had moved even with Cuomo in the polls. When the results came in last Tuesday, Mamdani had a seven-point lead over Cuomo, putting him on track for victory once the votes for the other candidates were redistributed.

Given NYC’s heavy Democratic lean, Mamdani enters this fall’s general mayoral election as the favorite, but victory isn’t a given. Cuomo is eligible to run in the general election on another party line and has not removed his name from the ballot after recent polling showed him running even with Mamdani. Moderates are also taking a second look at sitting Democratic Mayor Eric Adams, who is running for re-election as an independent after Democrats, exasperated by his right-ward drift, incompetence, and scandal-plagued administration, abandoned him. (Adams was under federal investigation for bribery and fraud until he cut a deal with the Trump administration to have the charges dropped in exchange for his cooperation on their deportation efforts.)

Progressives and other left-wing Democrats have argued Mamdani’s victory is a template for what Democratic candidates throughout the country need to do to defeat a MAGA-fueled GOP: Focus on affordability issues, run against the Democratic party establishment, develop an engaging social media presence, appear frequently on podcasts and other one-on-one media programs, embrace your liberal convictions, and rally young voters to your side.

On the other hand, moderate Democrats view Mamdani’s win as a disaster for a party that desperately needs to moderate its image and reconnect with voters turned off by its leftward tilt. Furthermore, moderates fear Mamdani’s criticism of Israel and past support for the “defund the police” movement will taint the entire party, and that his lack of experience, perceived laxity regarding crime, and socialist agenda—which they believe will stifle economic development—will ultimately reinforce the belief that America’s cities are failing due to poor Democratic governance.

I kind of come down in the middle of this debate, although I’ve also grown tired of this debate for reasons I’ll get to in a bit. First of all, my quick and dirty reaction to Mamdani’s win: 1.) The panic over Mamdani’s victory strikes me as overblown; 2.) I doubt Democrats can follow the playbook Mamdani used to win 43.5% of the vote in a Democratic primary in the United States’ largest city (which backed Kamala Harris 68-30% in the 2024 presidential election) when trying to win general elections in other parts of the U.S.; 3.) Concerns over Mamdani’s inexperience are legitimate; 4.) I would be concerned about Mamdani’s prospects as mayor given the recent poor track record of left-wing mayors in other American cities like San Francisco and Chicago, but Mamdani could correct for that if he governs as a pragmatic progressive rather than an ideologue; and 5.) But concerns about good governance should extend to centrist and establishment politicians as well; for examples, see Andrew Cuomo and Eric Adams.

As for the idea that a Mamdani mayoralty could stain the national party: Well, by now, Trump and every other elected Republican has called every Democrat out there a socialist and a communist, so the accusation has lost some of its punch. But I also think pundits are misreading any clues a mayoral election in New York City may have to offer. Again, this is just a primary, not a general election, but assuming the Democratic nominee will win in November even if other Democratic-affiliated candidates are on the ballot, that should be a good sign for progressives nationally. In 1993, Republican Rudy Giuliani’s victory presaged Newt Gingrich’s Republican takeover of Congress in 1994. Republican Michael Bloomberg’s win in 2001 following 9/11 mirrored the trust the country placed in Republicans in subsequent elections to wage the War on Terror. But just as Bloomberg’s party affiliation drifted from Republican to independent to Democratic, New York City’s political inclinations slid leftward as well. Bill de Blasio’s victory in 2013 denoted progressivism’s growing national influence, while centrist Eric Adams’ win in 2021 can be interpreted as a retreat from progressivism following the pandemic amid growing concerns about crime and immigration. If New York City is a barometer of national politics, a Mamdani win a few months from now could indicate the nation is ready for another round of progressive politics.

But back to the broader debate about the future of the Democratic Party that last week’s NYC mayoral primary has reignited. Democrats have spent the past eight months arguing over whether the party needs to move more to the left or to the center of the political spectrum. Parties are always going to have that debate. It may be Mamdani, despite the issues he addresses and the grassroots energy he has inspired, is tugging the party too far to the left. It may also be that Cuomo, despite his experience running government, would have pulled the party too far to the center and reasserted the stale party establishment’s claim to power.

But it’s getting to the point now where that debate is starting to harm the party. I don’t want to be that person who says we should just sweep our concerns under the rug and put on a happy face for the American people. If there are problems, we ought to air them. But a lot of the conversation going on right now among Democrats about the Democratic Party revolves around how “broken” the party is, and that runs the risk of signaling to voters that the party is beyond repair. You hear it from left-wingers like Mamdani, who made it a point to run against the party, as well as moderates like Pennsylvania Senator John Fetterman, who speaks about his low opinion of the party every time he steps in front of a microphone.

I’m aware public opinion polling shows the Democratic Party is not very popular at the moment. There are plenty of reasons for that. When people are fed up with the government and the political system, that’s hard on the party that takes a principled stand in defense of that. Additionally, many voters view the party as out of step politically and culturally with the part of America they come from or aspire to belong to. The Democratic Party is also polling poorly because there are lots of Democrats angry with their party for not doing enough to prevent Trump from returning to the White House and not doing more to stand up to him now as he vandalizes the country.

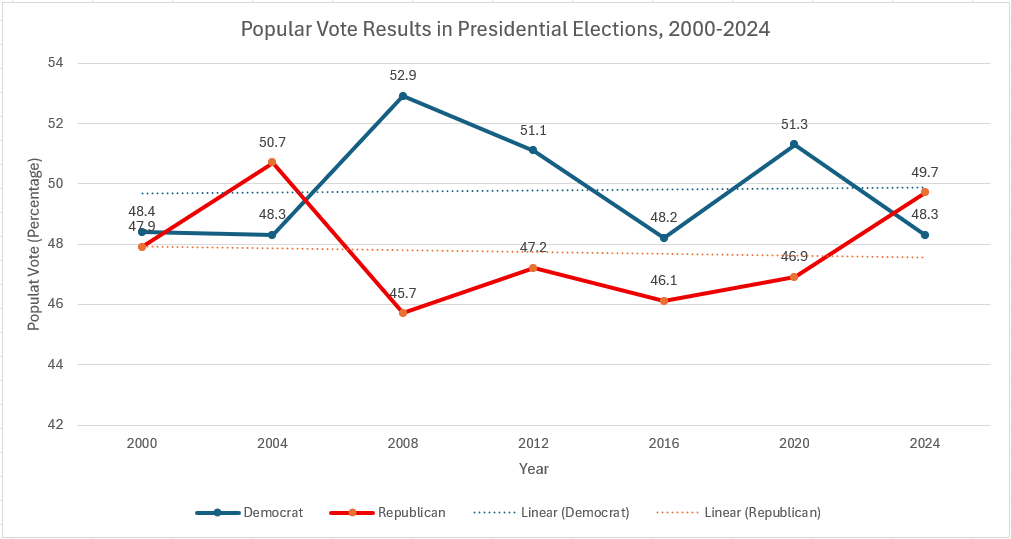

The Democratic Party, however, isn’t “broken.” Consider this chart, which shows the percentage of the popular vote won by the two major party candidates in each election dating back to 2000:

The Democratic Party did not crater in 2024. It essentially fared as poorly as it did whenever it lost a presidential election in the twenty-first century, which is to say not that badly. (Remember when Mitt Romney basically said in 2012 that 47% of Americans will always vote for the Democratic candidate for president? He was wrong: That number is actually 48.2%.) Granted, a party is only as good as its last election, so Democrats should be concerned about that 2024 result and Trump’s trendline (and let’s not forget the challenge the Electoral College will pose to Democrats’ prospects come 2030) but the point is Democrats head into presidential elections during a highly polarized era of American political history with a pretty decent foundation, and one that’s better than the Republican baseline to boot.

It’s one thing for Republicans to trash the Democratic Party; when Democrats pile on, they solidify that impression and potentially brand the party as such. Again, criticism is fine, but rather than tearing it down to advance a faction’s political ambitions, I’d rather see party leaders stepping forward to share how they would rehabilitate, rebuild, and strengthen the party. Parties drive people nuts, but they’re the engines that organize coalitions and drive elections, and Democrats need a strong party to defeat the MAGA movement.

To that end, I wish a prominent voice in the party would remind Democrats of the following:

While centrists often stray from the party’s ideological orientation, their views are often closest to the median voter. Because they’re usually trying to win elections in places where they can’t rely on liberals (or even Democrats) alone to put them over the top, centrists understand the importance of connecting with moderates, cross-pressured voters, and swing voters. Centrists make good points, and we need them to win.

While establishment Democrats are more attuned to what the party once was rather than what it is becoming and are often reluctant to cede power, they often have the keenest understanding of how politics works and what it takes to build a winning coalition. Their ideological flexibility helps them lead a big tent political party. Establishment Democrats make good points, and we need them to win.

While populists often hold traditional views that don’t sit easily alongside the party’s liberal orientation, their concerns are frequently connected to the pressing pocketbook issues working-class Americans wrestle with on a daily basis. Their common-sense approach to politics keeps the party grounded. Populists make good points, and we need them to win.

While progressives are often too wonky and elitist and struggle to connect with voters who don’t pay much attention to politics, they understand the need for good policy that can make a real, meaningful difference in the lives of voters. A party that believes in the power of government to do good needs progressives for the sake of good governance. Progressives make good points, and we need them to win.

While left-wing liberals are often either ahead of public opinion or hold beliefs that aren’t held by a majority of Americans, they hold the party accountable to its ideological convictions. Liberals know that without those moral commitments, the party would simply be about public administration and the exercise of power and leave many voters—especially in the base—uninspired. Left-wing liberals make good points, and we need them to win.

Democrats need to acknowledge that winning isn’t just a matter of picking one of those factions over the others but striking some sort of balance between them. There’s no secret formula to doing that, either. It requires someone in touch with the specific moment, who doesn’t just have an academic feel for how to pull that off but an instinct for it. When Democrats find that person, they should probably give them serious consideration for president.

There’s one other reason why Democrats need to focus more on strengthening the party than tearing it down. If a party can’t bring itself together around a platform or an ideology, it will end up organizing itself around an individual and become a cult of personality. Look no further than today’s Republican Party to see how well that’s worked out. I’m not interested in candidates who would raze the party so that they can tower over the rubble. I want someone who can build that party up.

Musical Interlude 1: “I’m Not Sleeping” by Bruce Springsteen (from Tracks II: The Lost Albums - Perfect World)

Signals and Noise

From Substack:

From The Atlantic:

“Trump Changed. The Intelligence Didn’t” by Shane Harris

“Sinwar’s March of Folly” by Jeffrey Goldberg

“‘Everybody Knows Khamenei’s Days Are Numbered’” by Arash Azizi

“The President’s Weapon: Why Does the Power to Launch a Nuclear Weapon Rest with a Single American?” by Tom Nichols

“Elon Musk Is Playing God” by Charlie Warzel and Hana Kiros

“The End of Publishing as We Know It” by Alex Reisner

“America’s Incarceration Rate Is in Serious Decline” by Keith Humphreys

“The Blockbuster That Captured a Growing American Rift” by Tyler Austin Harper

From the New York Times:

“If This Mideast War Is Over, Get Ready for Some Interesting Politics” by Thomas Friedman

From the Washington Post:

“Immigrants Drive Population Growth in a Graying America, Census Shows” by Marie-Rose Sheinerman and Nick Mourtoupalas

“A $250 bill and ‘WMAGA’: GOP Lawmakers Push Legislation Honoring Trump” by Joe Heim

From Vox:

“Trump Wants to Take Out Iran’s Nuclear Program. His Attacks May Backfire” by Michelle Bentley

“How the Supreme Court Paved the Way for ICE’s Lawlessness” by Ian Millhiser

From The New Republic:

“The Rich Should Be Paying More—and Yes, That Means Me” by Abigail Disney

From CNN:

“The Many Ugly Polls on Trump’s ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’” by Aaron Blake

From Pew Research Center:

“Behind Trump’s 2024 Victory, a More Racially and Ethnically Diverse Voter Coalition” by Hannah Hartig, Scott Keeter, Andrew Daniller, and Ted Van Green

From the Cato Institute:

“65 Percent of People Taken By ICE Had No Convictions, 93 Percent Had No Violent Convictions” by David J. Bier

Musical Interlude 2: “Rain in the River” by Bruce Springsteen (from Tracks II: The Lost Albums - Perfect World)

Top Five Records Music Review: Never Enough by Turnstile

The punk rock revolution, like many prior revolutions of both the musical and political variety, began as a reactionary movement. Tired of what rock and roll had morphed into in the 1970s—musically-sophisticated, technically-proficient, artistically-pretentious, over-produced, geriatric, long, soft—punk sought to take rock and roll back to its basics. Think the Ramones: Three chords, three verses, three minutes. But stripping rock and roll down to its bare essentials not only reinvigorated its rebellious spirit (if anything, punk was a rebellion against rock and roll) but unleashed a new era of creativity, with bands building out and building anew from the wreckage wrought by punk. In the immediate years following the 1977 punk explosion, we would get new wave, the ska revival, post-punk, goth rock, no-wave, dance punk, neo-psychedelia, new pop, synthpop, hardcore, and industrial, and later alternative rock, grunge, and Britpop, all derived in one way or another from punk.

Forty-five years ago, devotees of those genres may have considered it a grave artistic sin for the artists they adored to flirt with the sounds of a different genre. Even though those styles emerged from a common ancestor, their particular aesthetic strictures and punk’s obsession with purity and authenticity meant any cross-pollination could be a sign of selling-out, especially among the less-commercial and less-pop-oriented styles. For instance, it’s hard to imagine two genres of music more antithetical to one another in 1980 than hardcore (an extreme, louder, harder, faster, more aggressive form of punk that spit in the face of commercialism) and new wave (an industry term for mainstream rock that adopted punk’s spiky, stripped-down aesthetic) even though both are only one-stepped removed from punk.

But what are those distinctions today? A 20-year-old fan of either hardcore or new wave in 1980 is signing-up for Social Security this year. Listen to Black Flag on Spotify and the algorithm might start feeding you Blondie. Over the past half-century, these genres have developed their own unique sound and at times have drawn from other styles, but they’ve always tread carefully around their siblings. The Baltimore band Turnstile seems ready to facilitate a family reunion.

Turnstile is a hardcore band that has spent the past ten years slipping into the mainstream. Songs from their third album Glow On (2021), which experimented with synthpop, earned the band Grammy nominations. They’re now out with their fourth album Never Enough, which has benefitted from festival appearances that have caught the attention of Charli XCX and Metallica’s James Hetfield. It’s fitting Hetfield would latch onto them, as Metallica’s career trajectory—which saw the band morph from an uncompromising thrash metal band in the early 1980s into a mainstream heavy metal act in the early 1990s—mirrors their own. Given the realities of the music industry today, it’s doubtful Never Enough will move as many copies as the Black Album (actually, there are only eighteen albums that ever have) but Turnstile, like Metallica in the past, seems poised at least to breach that barrier between hard rock and the mainstream.

Turnstile’s hardcore roots are dialed down on Never Enough, employed at times more as texture than foundation. They tend to come and go during songs, providing listeners with moments of wild abandon before recoiling to build all that energy up again. The album’s new wave influences come via the debt the band owes to the sound of the Police: The shimmery Andy Summers-style guitar riffs, the delicate Stewart Copeland-style drumming, and in lead singer Brendan Yates Sting-like vocals, particularly in the way he drags out vowels and drops consonants at the end of words. You can hear all this at work in “Seein’ Stars/Birds”, which sounds like Zenyatta Mondatta making its way to the mosh pit:

But that’s not all that’s going on in that track. There’s an 80s pop-rock guitar solo on “Seein’ Stars” that resolves itself into a spaced-out flare. The opening of “Birds” feels borrowed from M83’s “Midnight City”, giving the song a cool, urban, slightly menacing vibe. The final part of “Birds”, which kicks in after the hardcore break, draws its influences from everywhere: Guitarist Pat McCrory and bassist “Freaky” Franz Lyons clean, lock-step playing recalls Metallica, but their bounce owes more to Rage Against the Machine. That in turn accentuates the Zach de la Rocha in Yates’ vocals.

While Turnstile grounds Never Enough in late-70s/early-80s punk-adjacent rock and roll, they’ve sprinkled sounds from the late-80s and early-90s all over it. Just take a listen to the record’s majestic title track, which leads off the album:

That opening is what exactly? “Go” by Moby? “Downtown Lights” by the Blue Nile? The Orb somehow? Is it trying to channel the mood of the Stone Roses? A few songs later on “Dull”, the debate over whether Yates is more influenced by Sting or de la Rocha is decided in favor of Perry Farrell of Jane’s Addiction. Yet while Turnstile draws inspiration from all sorts of sources across time, their music doesn’t feel derivative or stir up a sense of nostalgia. It’s more fresh than familiar. In their hands, the past is a springboard, not an anchor.

This stylistic cornucopia places heavy demands on their audience. It’s not just that a curious listener may be turned off by a detour into hardcore; it’s that their hardcore fanbase—a subculture notorious for their musical orthodoxy—may turn their back on the band after hearing a song like “Sunshower”, which begins with a blistering guitar attack before ending with a very mellow flute solo floating atop an ambient soundscape. That’s another commonality Never Enough may share with the Black Album: While that record expanded Metallica’s audience, it alienated many in their thrash metal fanbase, who now regarded the band as sellouts.

But Turnstile doesn’t seem to be following Metallica’s path. They’re still striving for their breakthrough, both commercially and artistically, as a band critics have positioned as a Next Big Thing. Yet Never Enough seems to say that whatever the band does, it’s, well, “never enough.” Their lyrics—used more to announce a theme rather explore an idea—are about reaching goals or experiencing what should be a peak moment only to learn it’s not the high they expected. “Bright lights are never what they seem,” Yates sings on “Sole”. Later, during “Sunshower”, he screams “My head is overjoyed/ And this is where I wanna be/ But I can’t feel a fuckin’ thing.” They’re so close, yet so far away, never finding what they’re looking for.

The issue it seems is that we’re at our most vulnerable when we as artists or lovers bear our souls to others. Suddenly, when it’s our big moment; when it feels like the stakes are highest; when we let our guard down and share with others our deepest, most personal thoughts and feelings; that’s when we find ourselves at the mercy of others. We give it our all, only to find more is demanded of us. “I’m happy to give myself away/ I’m happy to fix what I can’t change/ All because you know I care,” Yates sings on “I Care” (see Exit Music) before pleading in the chorus for whoever’s listening to now take care of him: “But do you really wanna fall apart?/ And do you really wanna break my heart in two?”

Fortunately for Turnstile, they have a fanbase that follows them on their musical journey and gives them the space they need to explore. Rather than reject them for working a flute solo into their album, their audience instead embraces the band’s restless spirit. That flute solo, all those ambient passages: It’s the sound of a trust fall, a band following their instincts and taking a flying leap from the stage knowing their crowd will catch them no matter what. Turnstile expresses their appreciation on “Birds”, a hardcore love letter to their fans and a celebration of the band’s camaraderie (“Finally I can see it/ These birds not meant to fly alone”). We owe Turnstile’s fans our gratitude for letting the band fly free so they can share their gifts and ambitions with us.