How Can the GOP Govern America When They Can't Even Govern Themselves?

PLUS: Reviews of "Glass Onion" and "The Pale Blue Eye"

The American people don’t care about the “inside baseball” of politics. Procedural matters related to things like the filibuster, the Electoral College, or Supreme Court nominations may fire up highly-engaged partisans, but they don’t move votes on Election Day. Low-engagement voters—voters who perhaps don’t follow politics on a daily basis, need to be persuaded to vote, or swing between parties from election to election—are more interested in basic questions: Is the government leading the country in the right direction? Is it addressing the issues that need to be addressed, and addressing these issues correctly? They could care less about process. They just expect results, specifically the *right* results.

These procedural matters are important, though, as they affect who has power in Washington and how that power will be wielded. In other words, outcomes are shaped by process. For example, the decision to overturn Roe v. Wade this past summer wasn’t simply the result of a 6-3 vote at the Supreme Court; it was also the result of Senate Republicans holding a seat on that Court open for over a year during Obama’s final year in office so they could hopefully fill it with a Republican president’s nominee (which they did) and then rapidly filling another seat that became vacant mere weeks before that same Republican president would lose the 2020 election.

Now, a lot of voters will just roll their eyes at a procedural dust-up like the one that played out this past week in the House of Representatives, where Republicans tried again and again and again to elect a Speaker. It took Republican Kevin McCarthy four days and fifteen excruciating roll call votes to finally triumph, and things got so heated late Friday night (January 6th, of all days) that one Republican member of Congress (Mike Rogers of Alabama) had to be physically restrained from attacking fellow Republican Rep. Matt Gaetz. My guess is most voters probably interpreted this entire four-day debacle as nothing more than a tug-of-war between Washington insiders, nearly all of whom—Republicans and Democrats alike—they despise. But every American should take note of what happened in Washington, D.C., this week, because that bit of process—essentially nothing more than a Republican House majority attempting to demonstrate that it does indeed have a majority—helps explain why we keep getting a very particular set of outcomes that have come to characterize American politics over the past twelve years: Mismanagement, dysfunction, and crisis.

Some caveats first: Some Republican apologists have argued that what we saw in the House this week was nothing more than democracy in action. Yes, it is true democracy is at times chaotic and messy, and we should be thankful for that. But don’t confuse the cacophonous chaos of democracy—a sound characterized by a multitude of diverse voices straining to be heard—with the sound of a Republican Party that not only can’t get its act together but keeps letting its loudest, most obnoxious voices speak for it. That deafening “democratic” noise you hear isn’t the sound of many people debating and speaking at the same time. It’s the sound of loudmouths shouting down those who won’t give them everything they want and those taking this verbal lashing (many of whom should know where all this is headed) screaming that they’ve somehow got this under control while trying to match the loudmouths’ outrage.

Also, it is admittedly very difficult in a legislative body for a majority party to get things done when they only have a narrow majority, which is precisely what the House Republican majority is dealing with during this Congress. The narrower the majority, the more every vote matters, the more every legislator must be satisfied, and the more likely defections from the party line will prove fatal to the party’s ambitions. When every legislator is voting yea-or-nay in the 435 member House, it takes 218 votes to win. Republicans are working with a 222 vote majority, giving them four votes to spare. That’s tough. It’s a dilemma Democrats should be able to appreciate following the 2021-22 congressional session, when all it took was a handful of legislators in either chamber to kill a bill.

But there’s a paradox here. When legislative margins are narrow, members of Congress are actually more likely to vote along party lines rather than buck their party. Why? First, with narrow margins, each party understands how easily they could either gain or lose control of the chamber in the next election, leading party members (particularly those in the minority) to draw stark contrasts with their opposition. They want to make it clear to voters that the parties are different from one another and that much would presumably change if control of the houses flipped. This is one reason why polarization is so pronounced in our times: Politicians have a tremendous electoral incentive to distinguish themselves from the opposition.

Secondly—and more importantly here—members understand nothing will get done if fellow party-members are constantly impeding legislation, so when margins are close, they demand greater party unity. To this end, the rank-and-file are often willing to cede power to their legislative leaders, including the power to craft legislation, manage party messaging, and impose party discipline. In such circumstances, party leaders are expected to smooth over party differences and guide the caucus as a whole rather than defer to various centers of power within the party, and the rank-and-file are expected to eventually get onboard with whatever deal their leaders put together. While it’s still hard for narrow majorities to pass big pieces of legislation with many moving parts along party lines, a sense of party unity is often more strongly felt among members of Congress when margins are slim.

Which makes what Kevin McCarthy had to endure this past week so bizarre. The source of McCarthy’s torment was a group of conservative hardliners who should presumably want a strong Speaker in order the maximize the conservative caucus’s political leverage. Yet reports indicate the deal these hardliners struck with McCarthy will severely weaken the Speaker’s power. As we’ll see, though, their game plan isn’t to strengthen the Speaker but to sideline him, or, as hardliner and Florida Man-Child Matt Gaetz said, to put McCarthy in a “straightjacket.” Their goal is to make sure McCarthy does their bidding even if McCarthy’s conscience and sense of responsibility to the nation as a whole somehow encourage him to do otherwise.

There are apparently two major procedural concessions McCarthy made. The first allows only one member of the majority to file a motion to “vacate the chair,” which forces a vote of the whole House on removing the Speaker. For the record, this rule has been in place for much of the House’s history, but it was very rarely used. When Democrats took over in 2019, they upped the number required to file a motion to vacate to half the caucus to ensure aggravated House Democrats weren’t constantly poking Pelosi with such votes. McCarthy wanted the number to vacate lowered to five. But the reason John Boehner left the speakership in 2015 was that then-representative and future Trump White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows (who was apparently working behind the scenes with the hardliners this week) had filed such a motion against Boehner and signaled he intended to make this a common practice. That would have hamstrung Boehner. McCarthy has a smaller majority than Boehner had to work with in 2015 but has now given those in his caucus who have made it abundantly clear this week that they don’t like him the power to hamstring him, potentially oust him, and plunge the House at any time back into another doom loop of Speaker votes.

The second concession involves the Rules Committee, the most important committee on Capitol Hill. The Rules Committee is controlled by the Speaker (its members are party loyalists) and sets the rules of debate for any bill headed to a floor vote. Not only does the Rules Committee establish how long a bill can be debated and how many amendments can be offered on the floor during debate, but it also decides the text of the bill under consideration. (That’s right: The Speaker can take a bill renaming a post office in Middle of Nowhere America after some local legend and turn it into a trillion-dollar omnibus spending bill.) The hardliners demanded enough membership on the Rules Committee to prevent the Speaker’s appointees from controlling this process. Because the Rules Committee has token Democratic membership, hardliners could vote “no” along with Democrats to keep McCarthy’s preferred bills from coming to the floor. And whatever bills do come to the floor may come with rules that allow carefully negotiated bills that have been worked out in committee or in the Speaker’s office to be shredded by the amendment process or debated ad nauseum. It’s a recipe for legislative breakdown.

Furthermore, McCarthy apparently agreed to the hardliners’ demand to play hardball with Biden and Senate Democrats on government spending and the debt ceiling until Democrats cave to their demands. Not only will that approach probably lead to more government shutdowns, but it threatens default on the government’s debt, which analysts have said could initiate a worldwide depression. That demand basically brings everything into focus, as it reveals the true stakes: The hardliners have made it clear Democrats and Republicans alike are either going to give them everything they want on fiscal matters—however unpalatable that may be—or (depending on the scenario) either the government ceases to function or a global economic meltdown commences.

So you can see where this is going. The hardliners want McCarthy to play the ultimate game of political hardball with the nation’s full faith and credit and the global economy on the line. They’re going to write the bills that enable him to do just that. If McCarthy blinks—if he cuts a deal with Democrats in the Rules Committee or on the floor to avert a shutdown or default—they’ll move to vacate, vote him out, and replay the chaos of this week until the rest of the Republican caucus agrees to let them win again by picking a Speaker willing to push the country over the edge. Or they could just render the House of Representatives powerless, unable to act to avert catastrophe.

None of this makes McCarthy a “strong” Speaker. A strong Speaker would be empowered by their caucus to craft legislative solutions that are in the best interests of the caucus as a whole, someone who can find ways to bridge differences between party factions while negotiating the best possible deal with the opposing party before whipping members with either carrots or sticks once the way forward emerges. We might call such a Speaker a “Pelosi.”

But that’s definitely not McCarthy. There’s plenty of Republican unity on issues of both the run-of-the-mill and hot-button variety to create the impression McCarthy has command over his caucus. But that command will prove a mirage on big ticket, high stakes legislation. In that moment, McCarthy will be exposed for what he is: A hostage, someone who surrendered the powers of the Speaker to get nothing in return simply so he could claim the mere title of Speaker.

What makes this all the weirder is that it isn’t as though McCarthy’s not someone the hardliners can’t conceivably get behind. It’s not just that McCarthy would be the most conservative Speaker of the past 100 years. It’s that this is the guy who led the effort to rehabilitate Trump, who even after denouncing Trump on the House floor in the hours after the 1/6 riot still voted to challenge the results of the 2020 election and within weeks made a pilgrimage to Mar-a-Lago to put things right with his party’s lead insurrectionist. McCarthy has no problem humiliating himself in front of the nation if that act of personal debasement can demonstrate his allegiance to the MAGA movement. Or maybe it’s actually the other way around: Maybe that willingness to sell himself out with no sense of shame has suggested to his hardline conservative opponents that McCarthy has the spine of an earthworm and is therefore too malleable and untrustworthy. Who knows.

Enough about McCarthy, though. He may have been made to suffer this past week, but the real power players—the ones who inflicted this torture upon McCarthy, the House Republican caucus, and, soon enough, the nation—are the conservative hardliners. But that label—“conservative hardliner”—doesn’t quite do them justice. Nearly every Republican in the House caucus is “conservative,” and given the way they’ve voted on the validity of our national elections and dealing with Donald Trump’s indiscretions, I’d characterize most of them as “hardliners.” And it’s not as though Matt Gaetz and Lauren Boebert are somehow more “hardline” than Jim Jordan or Marjorie Taylor Greene despite being on opposite sides of this week’s Speaker votes. It’s just that Jordan and Greene have convinced themselves that McCarthy is willing to do whatever crazy thing they want him to do while Gaetz and Boebert want to lock him into that.

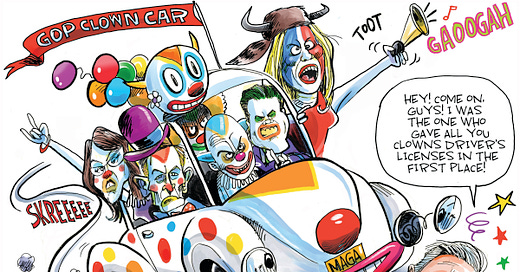

What we have here instead is a Clown Car Caucus that has no problem treating the necessary act of governance as a circus, and within that caucus a Joker Caucus prepared to put conscientious people in impossible situations and let the world burn if their demands aren’t met. And as much as I delighted in watching the Joker Caucus humiliate McCarthy and the Republican House caucus last week—you bet they deserved it, especially after McCarthy’s trek to Mar-a-Lago two years ago—in the end, it just isn’t funny. Believe what you will about conservative political priorities like spending cuts, lower taxation, and deregulation. Those amount to differences of opinion. They can be sorted out in negotiations and elections and the process of actual governance. But taking political hostages and threatening to act irresponsibly if your opponents and ostensible allies don’t surrender to your demands? That’s villainy.

Now it’s possible this all backfires completely on the Joker Caucus and inadvertently empowers moderate House Republicans (who could start playing hardball themselves with McCarthy and the Jokers) or even Democrats (who may find ways to inject themselves into the process or be called upon to ride in to the rescue.) Maybe the political winds shift in a few months and McCarthy unilaterally changes the deal. Instead, it’s more likely the process that unfolded this past week is a prelude to a political catastrophe. That makes it important to remember that this whole episode was orchestrated solely by 222 House Republicans who needed to find a way to get 218 of their members to vote for a (gasp!) Republican Speaker. Unlike past political crises, Republicans can’t sow confusion by claiming Democrats are somehow equally responsible for the mess the GOP made, that Democrats are “infringing on due process by rushing an impeachment trial” or “refusing to negotiate a spending bill in exchange for a debt ceiling hike” or “unfairly changing election laws” or “attacking Trump for something the Clintons did all the time.” Nope, this is all on House Republicans.

And the truth is all it would have taken was 4-5 House Republicans from the Cheney-Kinzinger Caucus to put a stop to it. They could have looked at the deal McCarthy made with the Jokers and said “no, we’re not onboard with that” and withheld their votes for McCarthy until he agreed to restore some sense of administrative responsibility to his caucus. They could have even done so by casting themselves as defenders of the conservative cause. But, predictably, they chose not to, proving once again that, as a party that can’t govern itself, the GOP shouldn’t be entrusted with governing the country.

I’ve become a broken record on this, but then again, there’s a reason I have to keep repeating it over and over again: If Republicans can’t fix this problem themselves, then voters need to use their ballots to fix it for them. The American people have had their chances, but until enough conscientious Republicans take it upon themselves to repudiate their own party, this problem isn’t going away. I know that’s a tall order in our heavily gerrymandered, highly polarized, evenly-split nation, but that’s the only way out.

From the Tea Party to the Freedom Caucus to Trump’s MAGA Movement to the Insurrectionists, hardline conservatives have only grown more emboldened in their assault on responsible governance over the past 10-15 years while the resistance offered up by the responsible wing of the Republican Party has withered. Fittingly empowered in the House on January 6, 2023, the Joker Caucus is the latest group to carry the hardline banner forward. The popular appeal of all these hardline groups is based on their utter disdain for “Washington.” What the events that took place last week on the floor of the House reveal, however, is that the problem isn’t “Washington,” but rather a select group of Clowns who have turned our politics into a malevolent spectacle. Their circus should have ended a long time ago. Instead, a new show’s just getting started.

Further Reading: “‘The Democrats, the Republicans and the Freedom Caucus’: Inside the Right’s Plans to Seize Power in the New Congress” by Steve Reilly and Maggie Severns, for Grid

Signals and Noise

Meanwhile, in Pennsylvania, a group of Republicans joined with the Democratic caucus to elect Mark Rozzi, a Democrat, Speaker of the Pennsylvania House. Republicans hold a slight edge in the chamber, which also has three vacancies. Rozzi has pledged to lead as an independent. And in Ohio, moderate Republicans joined with Democrats to elect a moderately conservative Republican Speaker of the Ohio House. A majority of the Republican caucus had voted for a right-winger for Speaker. It is not clear what deal Jason Stephens (the new Speaker) cut with Democrats, but speculation revolves around education spending and possibly fairer electoral maps (Ohio is one of the most gerrymandered states in the country.)

And no, I haven’t forgotten about freshman Rep. “George Santos.” Barring a pressing story that breaks in the coming days, I plan to write about the Talented Mr. “Santos” next week. Stay tuned.

Susan Glasser writes for The New Yorker that 2022 wasn’t a great year but could have been a lot worse.

Here we go: Don Trump has floated a third-party presidential bid if he doesn’t win the Republican nomination.

Here is a summary of the 1/6 Committee’s final report by Just Security.

Outgoing Arkansas Governor (and potential 2024 Republican presidential candidate) Asa Hutchinson has said the events of 1/6 have disqualified Trump from holding office again.

Watching the 1/6 riot unfold, Trump told those around him that day that he thought his supporters storming the Capitol looked “very trashy.”

“I’m African American. Child of the sixties. I think it would have been a vastly different response if those were African Americans trying to breach the Capitol. As a career law enforcement officer, part-time soldier, last five years full but, but a law enforcement officer my entire career, the law enforcement response would have been different.”—William J. Walker, head of the DC National Guard on 1/6 and current House sergeant at arms, in a January 6 Committee transcript.

Before Christmas, Congress passed the Electoral Count Act, which will make it harder to re-run the 2020 election debacle.

Just me wondering, but if Trump’s tax returns prove how “proudly successful” he has been at running his businesses, why didn’t he release them himself?

Meanwhile, Noah Bookbinder wonders for The Atlantic why the IRS audited Obama and Biden’s tax returns when they were president but not Trump’s. Hard to argue the feds treat Democrats differently from Republicans when the agency responsible for collecting taxes places Democratic presidents under more scrutiny than Trump.

By James Dobbin and Miriam Jordan of The New York Times: “Will Lifting Title 42 Cause a Border Crisis? It’s Already Here”. Prediction for the 2023-24 legislative session: The one major piece of legislation this Congress will generate will be an immigration bill.

Data from Vermont, Kentucky, and Nevada find that expanding early voting benefits neither party electorally. What is becoming clearer, however, is that villifying early voting—as Trump and other Republicans have done recently—disadvantages the party that does that, as it puts more weight on a single day of voting and more pressure on Election Day GOTV operations.

Umm…

Sarah Kaplan and Brady Jenner at the Washington Post report researchers at Brigham Young University expect Great Salt Lake—currently at 37% of its former volume—will disappear in five years time and expose millions to toxic dust found on the lake bed if further cuts to water consumption don’t occur.

Katelyn Jetelina describes China’s COVID outbreak with 5,000-10,000 people dying per day (at its peak, the U.S. lost 3,800 per day) as a “humanitarian disaster.”

The latest COVID variant—XBB.1.5—has shifted so far away from the original version of COVID that the antibodies used to date in vaccines and treatments and derived from previous infections do little to stop it.

The Biden administration is moving aggressively to curtail China’s technological development, a move that some say has the potential to limit China’s military and economic growth more than anything Trump did and reverses decades of US policy toward China.

During a meeting, Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin announced their intention to develop deeper strategic ties between their two countries.

While Russia has continued to fire missiles at Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, Ukraine carried out its deadliest attack on Russian forces on New Year’s Eve.

Benjamin Netanyahu is back in power in Israel and has brought with him a radical far-right coalition. As Yair Rosenberg writes for The Atlantic, “But even if [he] ultimately finds that he cannot control his monster, Netanyahu will have succeeded in rescuing himself from prosecution, the consummate political survivor living to fight another day. In the meantime, if the current coalition results in the hobbling of the country’s judiciary, the repression of its minorities, or the erosion of its democratic institutions and international standing, it’s a price Netanyahu is willing for Israelis to pay.”

Vincent’s Picks: Glass Onion and The Pale Blue Eye

Seeing Daniel Craig return in Glass Onion to his role as Benoit Blanc, the world’s greatest detective, from the 2019 film Knives Out by Rian Johnson (Looper, Star Wars: The Last Jedi) got me thinking about Craig’s other notable screen persona. No, I’m not talking about Joe Bang from Logan Lucky (definitely worth your time) but Agent 007 James Bond. That film franchise debuted in 1962 with Dr. No, which, despite memorably establishing many of the stylistic hallmarks of the Bond series, struggled at times to find its cinematic footing. (It’s often quite slow.) But producers used Dr. No as a learning experience, and when Bond returned to screens a year later in From Russia, With Love, they’d figured out how to make a Bond film hum.

Glass Onion (now streaming on Netflix) is to the Benoit Blanc series what From Russia, With Love is to the James Bond series. Where Knives Out was an enjoyable yet choppy film that struggled to draw viewers into its world, Glass Onion is a finely tuned machine full of style and verve and laugh-out-loud humor. You’ll be hooked from the start, at times luxuriating in the images on the screen, at other times frantically scanning compositions for information. It’s a blast.

The film centers on a party thrown on a private Greek island in the midst of the 2020 COVID lockdown by obnoxious tech billionaire Miles Bron (Edward Norton). Bron has invited a group of friends to join him: Governor Claire Debella (Kathryn Hahn), Bron’s head corporate scientist Lionel Toussaint, lifestyle entrepreneur Birdie Jay (Kate Hudson), and men’s rights social media influencer Duke Cody (Dave Bautista). Birdie is accompanied by her harried assistant Peg (Jessica Henwick) while Duke is joined by his girlfriend Whiskey (Madelyn Cline). Also showing up: Cassandra “Andi” Brand (the excellent Janelle Monáe), Miles’s ex-girlfriend who has recently shunned the group, and Blanc, whom we soon learn was not invited to the party by Miles yet somehow still received an invitation.

Miles and his friends call themselves “The Disruptors” for their willingness to buck social convention and charge boldly into the future. Their success in their respective fields has earned them adulation as trendsetters willing not only to break the system but all those other things no one wants them to break. This, to Miles, is a sign of genius: The willingness to chase down crazy ideas, push past comfort levels, speak truths others are afraid to utter, and turn a hunch into fame and fortune and power.

That notion of “disruption” is the source of much of the film’s social commentary, a feature Glass Onion shares in common with its predecessor but that is conveyed more effectively here. As you may suspect, there is perhaps a little less to the art of disruption than Miles suggests (as Blanc states in one of the film’s most memorable lines, “It’s a dangerous thing to mistake speaking without thought as speaking the truth,”) and perhaps greater responsibility that comes with disruption than Miles is willing to admit. As Blanc demonstrates, genius isn’t something that can be bought or assigned or announced but must be proven in practice. Additionally, the film shows how the wisest and most perceptive among us are very often those who don’t have the means to broadcast such attributes to the world. Johnson also peppers his screenplay with insights about the nature of truth, such as that knowing something about someone doesn’t always require certifiable proof, and that simply saying something is true when our own eyes tell us otherwise definitely doesn’t make that assertion true. By skewering his characters with these insights, Johnson ends up skewering the likes of Elon Musk, Kim Kardashian, Joe Rogan, Donald Trump, Gwyneth Paltrow, Peter Thiel, and Kanye West.

Anyway, eventually, there’s a murder, and Blanc sets out to solve it. Does the mystery add up? I don’t know; just as the characters in Glass Onion are constantly performing sleights of hand, Johnson is constantly doing the same thing cinematographically. Yet one never gets the sense the film is cheating, and the movie carries us along so quickly that we never obsess over the actual mechanics of the plot. We’re as equally engaged by the chase as we are the moral of the story, which is quite the achievement. Stitched together by an endless stream of one-liners and visual gags, Glass Onion is not only a first-rate entertainment but an intellectually stimulating experience.

And guiding us through this puzzle box is Daniel Craig’s Benoit Blanc, so quick and sincere with the ol’ Southern charm before those steel blue eyes sharpen at the sight of a clue or the slip of a tongue. He’s something we rarely see anymore at the movies: An original serial character. If Glass Onion is Blanc’s From Russia, With Love, well, knowing where the Bond series went from there, I can’t wait for the sequel.

Detective Augustus Landor (Christian Bale) is washing his hands in the frigid waters of a Hudson Valley stream during the winter of 1830 when he hears someone arrive at his homestead. The Army Captain waiting for him is there to summon Landor to the United States Military Academy at West Point, where a cadet has been found hanged. Shocking as that is, a more gruesome detail emerges: The academy’s doctor (Toby Jones) reveals to Landor that the victim’s heart has been carved out of his chest cavity. As Landor—a widower who is also grieving the loss of an adult daughter—begins investigating the crime, he soon gains the assistance of an inquisitive cadet whose timid, poetic, and awkward nature distinguishes him apart from his peers: Edgar Allen Poe (Harry Melling; that’s right, Dudley Dursley from the Harry Potter films, but last seen in The Queen’s Gambit.)

So begins the screen adaptation of Louis Bayard’s novel The Pale Blue Eye, another enticing mystery now streaming on Netflix. For the first hour or so, director Scott Cooper (Crazy Heart, Out of the Furnace, Antlers) weaves an intriguing tale whose clues keep us riveted but whose secrets aren’t too hard to discern. (Remember Roger Ebert’s Law of the Economy of Characters.) It also veers into the occult, with an expert in the subject matter (Robert Duvall) conveniently living nearby. Unfortunately, the film takes a lurid turn about halfway through its runtime—you can mark it by the appearance of Gillian Anderson (The X-Files, The Fall, The Crown), who seems well-aware of just how preposterous her role is—breaking the spell it had cast on viewers. Its final thirty minutes, however, go a long way toward salvaging the story.

I got the sense Cooper wanted to tell a more cerebral story here, one that didn’t necessarily have to turn on a fiery showdown. You can see this in the development of Poe’s character. Melling plays him brilliantly, knowing Poe must be both appealing and off-kilter but not so off-kilter that he’s a total weirdo. Yet Poe seems more like a device here, a hook intended to draw eyeballs to Netflix and whose development as a character is secondary to the needs of the plot. Poe should be more than a symbol of gothic America; he has a worldview, and it isn’t until the final scenes that we begin to see how that worldview gains depth and shapes his character.

Watch carefully, though, and you’ll find that version of a more provocative movie poking through. For instance, there is a scene midway through the film when Landor expresses his disdain for West Point, which he regards as an “institution” that uses “regulations” and “rules” to deprive its students of “reason” and “will.” He considers the Academy as guilty of this crime as the perpetrator. That marks Landor as a Transcendentalist, but one whose positive outlook on human nature seems to have faded. By contrast, the historical Poe rejected much of Transcendentalism, not necessarily its romantic inclinations, but certainly its optimism. Poe had a much dimmer view of human nature and dedicated his literary career to exploring the darker recesses of the human heart. That theme—how Poe’s dark romanticism undercut Transcendental optimism—is present in the film. You can see it in the contrast between the darkness of the woods and the snow on the ground, and in the final shot of a white ribbon floating away in the wind. But I suspect a deeper meditation on that theme and how those ideas could have taken root in Poe during the fictional events of this film were sacrificed for the sake of plot.

Yet in the depths of winter, you could certainly do worse than this picture. The warmth of its fireplaces, along with the mountains of melted wax from flaming candles placed on tabletops, offers a sharp contrast with its snowy setting. It’s chilly and cozy all at the same time, perfect for a January evening. And those looking for a cameo by a raven won’t be disappointed.