An Idea For the 2024 Democratic Ticket That's So Crazy It Just Might Work

PLUS: Time-traveling and universe-hopping with Spider-Man, the Flash, and Indiana Jones

There is some unease within the Democratic Party about President Joe Biden’s standing with the American public. His aggregate approval rating according to FiveThirtyEight.com has sat at between 40-41% all summer, which is down a few tics from where it was most of the past year. What’s also disconcerting is that his numbers are very sticky, having barely budged from around 42% since October 2021 even though in that time he has successfully moved the nation past the pandemic, enacted major legislation, steered the country toward a green energy future, united the West in support of Ukraine, and can take credit for a low unemployment/low inflation economy.

Given today’s political polarization, contemporary presidents probably cannot expect to enjoy the higher levels of popularity presidents in the recent past experienced. The electorate—particularly at the national level—has sorted itself into more ideologically-constrained parties whose partisans automatically disapprove of members of the opposing party no matter how steady their leadership may be. Yet Biden’s numbers remain stubbornly low, dragged down not only by Republicans who refuse to lend him any support but also by underwhelmed independent voters and a not insignificant chunk of disenchanted liberal voters who expected more from his administration.

I think the liberal critique of Biden is rather unfair. Given his legislative margins and the conservative tilt of the judicial system, I did not anticipate much from a Biden administration to begin with. Yet Biden’s accomplishments have exceeded my expectations. He also doesn’t get the credit he deserves for running a drama-free administration. Biden may not rank among the most charismatic of presidents, but he is a steady hand in tumultuous times, which ought to count for something.

Still, I can see how many Americans would see unsteadiness in Biden’s performance. That can mostly be chalked up to his age and a concern he may be slipping or faltering as he enters his 80s. It’s not just the way he moves, either; he’s not as smooth a public speaker as he used to be. The White House seems to be limiting his public events to keep these episodes from further eroding public support for Biden, but that can sometimes make it appear Biden is hiding from the public or only fit for stage-managed events. Again, I think some of this critique is unfair: I actually think Biden is more disciplined as president than he was as vice president, and when he does do interviews or speak contemporaneously, he demonstrates engagement with and command of the issues. He is not, as his critics would claim, a doddering, senile old man. More than anything, he strikes me as a veteran politician more interested in behind-the-scenes politicking and governance (where the actual work gets done) than in the superficial theater of politics at this point in his life.

I would like to say Biden’s public appearances don’t matter, that what only matters is his stewardship of the government and his skill when it comes to negotiating with other politicians, but the theater does matter to the extent that a president must instill confidence in their leadership and articulate a vision for the country the people can rally around. I know we’re not living inside an episode of The West Wing, where political disputes can be wrapped up within an hour with a rousing, perfectly-pitched speech, and it’s easy for politicians to lean heavily on the spectacle of politics at the expense of its substance. If a president errs in one direction or the other, I’d prefer they err toward being more substance over spectacle. But the president has to bring the people along as a public-facing figure as well, and in this regard, Biden seems to struggle.

I think there is also a sense among the American people that Biden is not the man for this time. You can chalk that up to his age but also to a 50-year career in national politics: First elected to the Senate in 1972 (the year Richard Nixon won re-election), he ran for president in 1988 and 2008 before finally succeeding in 2020. He won that year because he was a trustworthy, low-risk alternative to Donald Trump, someone who could tamp down the chaos that had engulfed the nation, return a sense of normalcy to American politics, and, dare I say, make America dignified again. I’m pretty sure he’d win a straightforward rematch with Trump, but no one should take that for granted. But his status as an elder statesman in a nation that has always been skeptical of politicians puts him at an uncomfortable remove from the people. The potential is there for either party to reap a significant electoral reward if they were to nominate a fresh face for president in 2024.

While I think he’s done a good job as chief executive, Joe Biden was not my preferred choice for president in 2020, and one part of me wishes he would step aside to let someone else run in 2024. I think most Americans always envisioned him as a caretaker president who could push reset on the country and then hand the country off in better shape four years later (hopefully to a new generation of Democrats.) The other part of me, however, appreciates how Biden has positioned himself to appeal to both Sanders-style progressives and Manchin-style moderates. When confronting reactionary demagogues in other western democracies, parties often either swing toward left-wing ideologues or bland middle-of-the-road politicians hoping to either motivate the base to head to the polls or form a grand coalition, respectively. Biden is certainly more of the latter than the former, but what he’s done is wisely serve as the mediator of this coalition, pushing moderates to advance a liberal agenda while also acceding to moderate demands for restraint. Getting this diverse coalition to cooperate with one another and prove it can deliver for the American people has been the key to his success as president, and there aren’t really any other Democratic politicians in the country not named Pelosi as well-positioned to pull this off as he is.

Biden has been branded too liberal and not liberal enough by his critics, but that twin critique is also a sign his appeal is pretty broad-based. He’ll need that to beat the Trump die-hards. But Biden has another advantage against Trump that often goes unmentioned, which is that Biden is a known quantity. The American people would have to vet a new Democratic nominee, and who knows what minor aspect of that person’s life Trump could blow out of proportion and voters could get hung-up on. The Hunter Biden stuff doesn’t really dog Biden because voters can check the president’s record and see his son’s affairs haven’t shaped his governance. A new nominee would be a blank slate for Republicans to write on.

Consequently, it’s highly unlikely Biden would shock the world and take himself out of the running for president in 2024, and barring any new development that undermines him politically, it probably isn’t worth pushing him to step aside, either. But Biden could benefit by injecting something new into his campaign, and I have a crazy idea that just might work.

One of the major letdowns from Biden’s term in office has been the standing of Vice President Kamala Harris. As a relatively young minority woman who had spent some time on the national stage as a United States Senator, Harris was the obvious choice for VP in 2020. I even thought on paper she was the best positioned politician to win the Democratic nomination for president that year. Yet she’s never gained traction as vice president, and her approval ratings are lower than Biden’s. Some of that can be attributed to certain Americans’ skepticism of women and minorities (and minority women) in positions of leadership. But insider reporting from the White House and Capitol Hill suggest she has left those who work more closely with her disappointed with her performance.

In one sense, this is perhaps not surprising, since she underwhelmed on the campaign trail in 2019 as a presidential candidate and just couldn’t click with voters in the early primary states. But if anyone should be blamed for her performance as vice president so far, it should be Biden himself, who should know more than virtually any other American what it takes to be a successful vice president and how to form a successful partnership with the president. Maybe pandemic restrictions from 2021 kept Biden and Harris from developing a stronger working relationship early in Biden’s presidency, but it also seems the White House has neglected to nurture her political skills. Now they’re paying a price, as they’ve turned a potential asset into a liability who can only be deployed under certain conditions on the campaign trail.

It’s hard to know what exactly is to blame for Harris’s lackluster vice presidency. Unfortunately, it may be too late to salvage her reputation for the 2024 campaign. Also, given Biden’s advanced age, the public’s confidence in his vice president may weigh more heavily in voters’ minds in 2024 than in 2020. I don’t think Biden can just drop her from the ticket—that would raise too many questions about his judgment and draw the ire of Democrats who would see it as the unfair dismissal of a politically imperiled woman of color—but he could make a different move: Appoint Harris Attorney General.

Attorney General Merrick Garland is not an indispensable member of the Cabinet. If anything, he has moved too cautiously in exercising the powers of the DOJ. (Some might argue that caution is warranted, as a more hesitant approach can build greater trust with the public. A hasty prosecution of Trump-era and Trump-related crimes could also be seen as overzealous. but that’s what Trump and his defenders are going to scream regardless.) But it might make sense once Trump is yet again the GOP’s nominee for president for Biden to ask Garland to head up an independent special prosecutor’s office tasked with overseeing all federal investigations into both Trump and Biden to better shield the DOJ from accusations of political interference during the 2024 campaign.

That would of course create an opening at Attorney General, one Kamala Harris—the former Attorney General of California—would be well-suited to fill. One could argue her talents are better suited to that position than to vice president. It would also mean she could exercise real administrative power rather than dwelling in the shadow of a president who keeps her outside his inner circle.

Harris might balk at the move, especially as it might be seen as a demotion. It doesn’t need to be viewed that way, though, as the position of Attorney General by custom actually has greater political independence than vice president and has far more official responsibilities. It would mean she wouldn’t be next in line to be president, but while serving as vice president for a man who will be between 82-86 years old as president provides her with a good shot at becoming president, counting on the death of your boss isn’t a good look. Moving over to DOJ wouldn’t keep her from running for president in 2028, either; it could actually burnish her resume. And given her underwhelming record as vice president so far, she wouldn’t clear the field in 2028 if she remained VP and may not even be the favorite to win that year regardless.

After the Democratic Senate confirms Harris, they could then move to confirm Biden’s pick to serve as his new vice president. Biden could pick a placeholder who would serve until January 2025 or nominate the person he wants to run with in 2024. Either way, it would give Biden the chance to bring a fresh look to the ticket (which is an advantage Trump, running without Pence this time, will have.)

Biden almost certainly prefers to stay on the path he’s on. Picking a new vice president may only end up opening new lines of attack against his leadership, and Senate Republicans may relish grilling a Democratic VP nominee in what might become rather prickly hearings. There’s no guarantee the new vice presidential nominee would perform better than Harris, either. (I’m recalling how gifted Ron DeSantis seemed as a politician before he had to hit the campaign trail as a presidential candidate.) Finally, it’s uncertain how much of a drag Harris really is politically, as most voters mainly choose who to vote for based on the name at the top of the ticket. My proposal is probably too clever by half. But if Americans’ unease with the Biden-Harris ticket deepens, I offer it as a way forward.

Counterpoint: “Yes, Joe Biden Is Old. Is That All Republicans Have to Run On?” by Molly Jong-Fast of Vanity Fair

Signals and Noise

Senator Tommy Tuberville sure had himself a week.

By Tal Axelrod of ABC News: “Trump’s Unprecedented Campaign Pitch: Elect Me to Get Revenge on the Government”

Don Trump is picking fights with influential Iowa Republicans such as Governor Kim Reynolds and evangelical leader Bob Vander Plaats, testing his belief that his personal brand is stronger in Iowa than those of state leaders.

Amy Walter of the Cook Political Report writes that while Republicans have rallied behind Trump following his indictments, that does not mean they will vote for him, particularly if it comes to be viewed as a political liability.

Still, Jill Colvin and Steve Peoples of AP report many Republicans think Trump is unstoppable at this point.

South Carolina Senator and Republican candidate for president Tim Scott is about to get his turn in the national spotlight.

Kyle Tharp of FWIW notices North Dakota Governor and Republican presidential candidate Doug Burgum is offering people a $20 Visa or Mastercard gift card if they donate at least $1 to his campaign (see below). Burgum needs 40,000 unique donors to qualify for the first Republican presidential debate.

Steven Shepard of Politico notes amidst concern about potential third-party candidacies for president that third-party candidates have generally fared the worst in toss-up states.

Hardline House Republicans are threatening to block must-pass appropriations bills unless Speaker Kevin McCarthy agrees to cut spending below the levels agreed to with President Biden during the debt ceiling showdown. (The GOP House did manage to pass a defense appropriations bill, but floor amendments added to the bill concerning abortion restrictions won’t make it through the Senate.)

Tony Romm of the Washington Post takes a look at the Republican politicians who voted against the infrastructure bill but now run around their states cutting ribbons on the projects that bill funded.

The supposedly “missing” witness in the House Republican investigation of the Biden family is accused of being an unregistered federal agent for China and an international arms trafficker in charges that were unsealed Monday.

By Eric Hananoki of Media Matters: “McCarthy-Backed House Candidate is Getting Help From an Antisemitic Podcaster Who Wants Political Leaders Assassinated”

Low inflation coupled with low unemployment: Is Bidenomics a thing? So asks Adam Cancryn of Politico.

By Catherine Rampell of the Washington Post: “Biden is Quietly Reversing Trump’s Sabotage of Obamacare”

A judge in New York ordered the state to redraw its congressional districts, which could net Democrats as many as six seats in Congress.

Florida’s “election security” office has levied over $100,000 worth of fines against both for-profit and non-profit third party voter registration groups. So far this year, less than 2,500 new voters have registered in Florida through the efforts of third party groups compared to over 63,000 by this point in 2019.

A Republican attorney in Ohio told a judge he voted twice (once in Ohio, once in Florida) in each of the past two elections on accident. (On both occasions, he voted within a week’s time in both places.)

Justice Clarence Thomas argued in a baffling concurrence to the Supreme Court case gutting affirmative action that the 14th Amendment and Reconstruction policies like the Freedmen’s Bureau were race-neutral. Adam Serwer of The Atlantic tears Thomas’s so-called “originalist” argument apart.

Brian Slodysko and Eric Tucker of AP look at how Supreme Court justices (with a focus on Sonia Sotomayor) push public institutions they speak at to buy their books and increase the profits they receive from those sales.

Tom Jackman and Emily Davies of the Washington Post report “ghost guns”—guns assembled from untraceable parts bought online—are gaining popularity among teenagers who cannot purchase guns in stores.

Iowa has made abortion illegal once a fetal heartbeat can be detected, which usually occurs around six weeks. Abortion had been legal in Iowa up to 20 weeks.

The FDA has approved the first over-the-counter birth control pill for sale.

According to a University of Michigan study, consumer sentiment in the United States is the highest it’s been since September 2021.

The IRS has collected $38 million from 175 high-income tax delinquents over the past few months.

By Sarah Kaplan of the Washington Post: “Floods, Fires and Deadly Heat are the Alarm Bells of a Planet on the Brink”

By Ruxandra Guidi of The Atlantic: “When Will the Southwest Become Unlivable?”

The Wall Street Journal looks at the thousands of miles of toxic lead-covered cables strung throughout the nation by telecom companies that are now degrading and polluting the places where Americans live, work, and play.

Russia is holding thousands of Ukrainian civilians in occupied Ukraine in prisons and labor camps and plan on building many more.

Sudan is on the brink of a full-scale civil war.

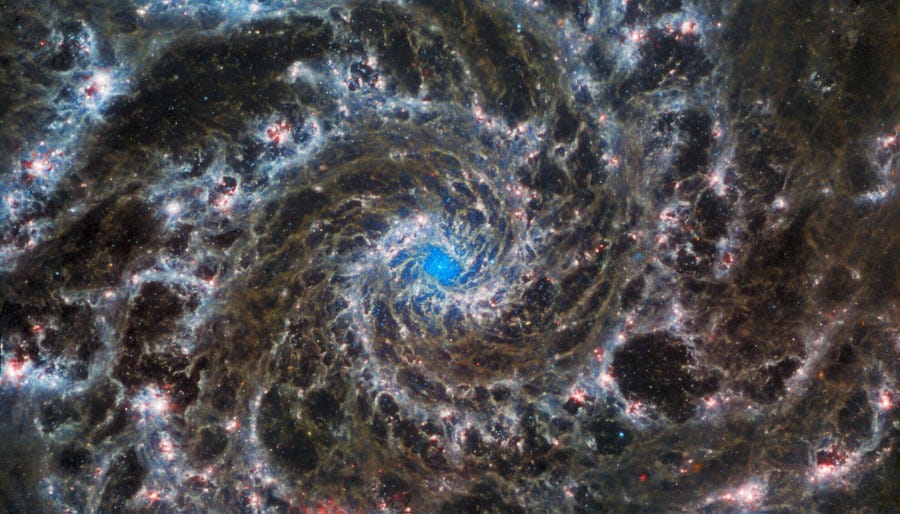

If you think this image of the Phantom Galaxy (which can be found 32 million light years away from Earth) is cool, check out more pictures of our universe taken by the James Webb Space Telescope.

Vincent’s Picks: Time-Traveling and Universe-Hopping with Spider-Man, the Flash and Indiana Jones

This past June, Hollywood released not one nor two but three tentpole films involving time travel and alternate realities: Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, The Flash, and Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. Additionally, the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) is currently in the middle of a multifilm-and-TV-show epic it is calling “The Multiverse Saga.” This year’s Best Picture winner at the Academy Awards, Everything Everywhere All At Once, was also set in the so-called “multiverse” where all possible realities reside. One may wonder why films about altered timelines and altered realities keep making appearances in this timeline and this reality.

A big part of it may be the economics of the film business these days. Given how hard it is to convince people to turn off the hi-def big screen TVs in their living rooms and shell out a month’s worth of Netflix to watch a two-hour movie in a real deal movie theater, Hollywood for over a decade now has been turning to established IP to lure viewers into cinemas. That means we’re subjected to a lot of remakes, product spin-offs, sequels, and franchise films. Eventually, for perhaps reasons creative or economic, the impulse arises to tie all the films in a franchise together, and one way this can be achieved, particularly in science-fiction movies, is by introducing time travel and alternate realities.

Universe hopping and time traveling in franchise films can be fun in the way these movies call back to earlier iterations of characters played by other actors, re-imagine the plots of earlier films, tie various editions of franchises together into one overarching narrative, and tickle our brains as we try to keep timelines and the mind-bending implications of time travel straight. (For good examples, see Star Trek from 2009 and X-Men: Days of Future Past from 2014.) They are also often nostalgia trips, sending contemporary characters back in time to eras older audiences may pine for or bringing back characters beloved by older generation. But these moves can just as easily come across as fan service, a marketing scheme rather than actual movie-making, while also catering to an obsessive (and at times toxic) segment of the fan base that demands tight continuity from films produced across different eras and different studios that were never intended to crossover. That may account for why The Flash, which brought Michael Keaton back as Batman, failed at the box office. Audiences may have seen that move as a gimmick or concluded any film released in 2023 that relied on characters from a 1989 movie would be too convoluted to follow.

Or maybe too much time travel and universe hopping makes whatever story that is being told insignificant. If past stories can always be retconned, then how serious are the stakes in any story we’re following? Dead characters can come back to life, entire story arcs can be erased, and all that money we spent on past movies in the series is a waste now. Play too much with time travel and you don’t just run the risk of breaking the sacred timeline but the audience’s patience as well.

But what if we take time travel and universe hopping as a serious theme that would presumably resonate with audiences today? Does the prevalence of these films, with characters jumping forward and backward and across time to fix the timeline or repair reality, suggest a profound sense of regret with the way things have worked out in our time and in our reality? Might it touch on a nagging feeling many of us have that we’re not living in the best of all possible worlds and ought to do something about that?

Not quite, it seems. Consider the MCU, where time-travel and universe hopping is now at the center of its main storyline. Time-travel was introduced to the MCU in Avengers: Endgame in 2019 as a way for the film’s superheroes to correct a devastating loss. It worked, and the clever way the heroes managed the consequences of time-travel (the problem isn’t that traveling back in time alters the future but spins off new realities that could imperil other realities) contained the fall-out of their decision to do so (although it’s probably for the best if we don’t think too hard about the implications of Captain America’s decision in the film’s final scene.) But now that the multiversal cat is out of its bag, the MCU is knee-deep in a long series of films and TV shows featuring the multiversal escapades of Spider-Man, Dr. Strange, the Scarlet Witch, Loki, and Ant-Man. There’s also an animated television show called What If? that tours these different realities. It’s all coming to a head in the character of Kang, a warlord who keeps popping up in rogue timelines and then sets out to conquer other timelines. (Kang is played by Jonathan Majors, whose recent legal troubles may necessitate a casting retcon in our own reality.) Increasingly, the MCU’s message seems to be a conservative one: This world is the way it is for a reason, so don’t mess with it. Like Spider-Man or the Scarlet Witch, our desire to improve it will only probably make things worse. Despite the temptation to change it, it is better to accept the world—warts and all—as it is.

The latest Indiana Jones film puts a slightly different spin on that idea. In Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, it’s not Harrison Ford’s iconic main character who hopes to journey to the past to tweak history. Instead, it’s a German rocket scientist played by Mads Mikkelsen who wants to locate the remnants of an Antikythera mechanism created by the ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes and use it to travel back in time to restore the Third Reich. It falls to the 70-year-old archaeologist to prevent the Nazi and his redneck goons from making fascism great again.

For reasons I won’t spoil, however, Dr. Jones is also dealing with some heavy personal issues. He’s spent a lifetime studying the past and would likely find relief if he could just drift back into the pages of the history books his students don’t bother to read. You could say he belongs in a museum. Dial of Destiny argues, though, that time should only march forward, can heal all wounds eventually, and that there is a place for a relic like Indiana Jones—an original action hero of the silver screen—in our world of cinematic superheroes. Yet the film does that by pouring on the nostalgia: We get to watch a de-aged Ford in action early on, and call backs to earlier films (i.e., a chase across the roof of a train, the perilous exploration of a hidden temple, a plane bombarded by arrows) give viewers a sense of deja vu. You can’t revisit the past, but maybe you can recreate it?

Of all the time-travel/universe-hopping movies that came out this summer, the one you should definitely see is Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, the sequel to the 2018 film Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. I’d consider that 2018 film the greatest comic book film ever made and a milestone of cinema, period. And don’t just take my word for it: When that film ended and the theater lights came up, my then seven-year-old daughter turned to me in awe and declared, “I think that was a really good movie.”

That’s the sort of film these Spider-Verse movies are. Bounding with creative energy and ideas, these pictures delight in their own imaginative powers. The movies are a collision of animation styles, as overwhelming as they are beautiful. They’re the sort of films you just want to wash over you. They’re also exuberantly American, capturing the spirit and diversity of the nation and splashing it across a pop cultural medium.

The Spider-Man most people are familiar with is Peter Parker, a nerdy, wise-cracking, white teenager from Queens who gets his superpowers from a radioactive spider bite. (His origin story is by now the stuff of legend.) He learns the hard way that with great power comes great responsibility, and despite suffering loss throughout his life, Parker always manages to find his way through hard times with his optimism and good spirit intact. The Spider-Verse movies, however, are centered on the comic-book character Miles Morales, a Black Latino New Yorker from an alternative reality who also develops spider-like powers after being bitten by an irradiated spider. Gathering spider-men and spider-women and even a spider-pig from across the Spider-verse, the first film implies Spider-Man can be anyone, an idea conveyed not only by the plot but by the animation as well.

The second film interrogates the idea of what makes someone a Spider-person. Even though every Spider-Man is different (and this film gives us spider-people who are Indian, pregnant, a British punk, a cowboy, in a wheelchair, a Lego character, a virtual reality character, etc.,) they are all subject to so-called “canon events” (i.e., the deaths of Uncle Ben-like characters) that define the arc of spider-people’s lives. Miles is not having that—why should a hero have to suffer, why shouldn’t the hero try to prevent suffering, couldn’t suffering actually prevent personal growth?—and wants to write his own arc. The leader of the Spider Society, a ninja vampire Spider-Man from an alternate 2099 voiced by Oscar Isaac, is determined to prevent Miles from altering his fate, as doing so would collapse a reality and destroy the lives of those in it. Miles believes he can find a way to keep that from happening. Unlike the other films I’ve reviewed so far, in this movie, we end up rooting for Miles to triumph and find a way to change his destiny. He ought to be able to, after all, and there’s no reason to assume the status quo is better than the alternative. Why not imagine a better world and seek to avoid obviously bad outcomes? This sequel isn’t simply about the value and power of diversity, but about an individual’s ability to write their own stories in an America that sometimes feels too constrained and where fates sometimes feel too preordained.

The Spider-Verse films, then, are an exception in the genre of time-travel/universe-hopping films: They actually embrace their characters’ reality-altering actions. (Or at least so far: We’ll see what the third film in this trilogy has to say about this when it hits theaters next spring.) According to the Spider-Verse, we should regard the future as a canvas upon which we as artists are painting our own masterpieces. But as this year’s Best Picture winner reminds us, if you can be everything everywhere all at once, sometimes you end up feeling like Jobu Tupaki: Nothing nowhere right now. That film seemed to play with every aspect of the multiverse, from our ability to become something more than we are in the moment and fulfill our potential to reminding us to accept people for who they are as we encounter them on a daily basis.

More than anything else, maybe these films speak to the anxiety many of us feel living in a liberal, democratic society, a place where change can happen fast and fortunes can turn on a dime, where we can remake ourselves overnight and the future is always up for grabs. That can be a liberating, frustrating, or frightening feeling. And perhaps it’s a relief for many to see so much at stake—our past, present, and future, our very reality—and watch as a hero sets it all right in about two hours time.