A Century Ago, American Democracy Had a Near-Death Experience

PLUS: A review of Peacock's new reality game show "The Traitors"

A basic history of twentieth-century America moves from the Progressive Era (roughly 1901-1917) to the United States’ involvement in World War I (1917-the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918) to the Roaring Twenties. But notice there’s a little gap there at the end of the 1910s. If you were lucky enough to have a good American History teacher, they probably would have taught you three things happened in this time: 1.) The 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote was ratified; 2.) The United States Senate refused to join the League of Nations even though its architect was American President Woodrow Wilson; and 3.) There was a Red Scare sparked by the Russian Revolution. But then you’d quickly learn Americans had grown so exhausted by their experience in the Great War that they longed for a “return to normalcy,” swept do-nothing Warren G. Harding into the White House in a landslide, and then threw themselves a wild party, with flappers, bootleggers, Babe Ruth, and Hollywood’s silent screen stars all in attendance.

But that’s not the full story. In fact, we as a country seem to have developed a kind of collective amnesia when it comes to the period between 1917 and 1921. It shouldn’t be glossed over. This era—chronicled in Adam Hochschild’s new history American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis—is one of the darkest, most disgraceful moments in American history, a time of lethal mob justice, racial violence, censorship, surveillance, and political imprisonment. The persecuted included German-Americans, Jewish people, immigrants, Black Americans, labor activists, socialists, conscientious objectors, and opponents of the war. When the government wasn’t turning a blind eye to the actions of vigilante groups, it often served as the agent of oppression. At a moment when there is good reason to believe the future of democracy in the United States is in jeopardy, it is worth revisiting a period a little over a century ago when American democracy and the rule of law completely broke down.

World War I was preceded by the Progressive Era, a time when the United States attempted to tame the upheaval wrought by industrialization and the laissez faire excesses of the Gilded Age. Driven by America’s growing middle class, progressives supported political reforms, government regulations, and social movements aimed at alleviating poverty, ending political corruption, countering the power of big business, and improving living conditions in America’s cities. With the frontier closed and the Wild West a thing of the past, the Progressive Era is often remembered as a gentle, civilized age, one more refined than past eras but not yet convulsed by modernity. We still recall it with nostalgia: One of the most iconic works of Americana—Disneyland’s Main Street, U.S.A.—is a simulacrum of a middle American small town from the Progressive Era.

Yet while the Progressive Era did in fact make a lot of progress (i.e., the Pure Food and Drug Act, trustbusting, a federal income tax, labor laws, conservation programs, the Federal Reserve system, etc.) the United States during this time was still roiled by social tumult. Immigrants poured into the country, with many finding low-wage employment alongside native-born working-class Americans in factories and other labor-intensive industrial settings. Often toiling for long hours in dangerous conditions, these impoverished workers frequently came into conflict with the wealthy businessmen who regarded them as cheap and exploitable sources of labor. With their lives and livelihoods on the line, many workers attempted to form unions to leverage their collective might against their employers or joined socialist or anarchist parties to affect political change. Labor unrest was common and often turned violent. Sometimes that violence was initiated by radical labor activists, but big business was just as likely—if not more likely—to use strikebreakers or armed government agents to forcibly suppress workers demanding safe working conditions, decent pay, and shorter working days.

Additionally, many of the immigrants arriving in this period came from southern and eastern European countries that had not traditionally sent many migrants to the United States. Large numbers of Germans still made their way across the Atlantic, but now they were joined by Italians, Poles, Russians, and Slavs. Many brought their Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Jewish faiths to their new predominantly Protestant home. At a time when the Anglo-Saxon establishment believed positive genetic traits explained the success of the Anglo-Saxon race as well as what they believed to be the criminality, slovenliness, and intellectual deficiencies of non-Anglo-Saxon people, many in the United States regarded this new wave of immigration as a threat to the nation’s future well-being. This nativism also helped fuel native-born working-class resentment of immigrants, with native-born workers fearing these new migrants suppressed wage growth and undermined their job prospects.

Meanwhile, any hope Black Americans had of attaining equality in the United States following the Civil War had been dashed. Jim Crow had been established in the South, and Blacks who ran afoul of white authority were lynched on a near-daily basis between 1890 and 1920, sometimes as a public spectacle. (It should be noted that while most lynchings occurred in the South, lynchings were not at all confined to that locale.) As memories of the Civil War faded and reconciliation between the nation’s regions became politically expedient, concern for civil rights was swept under the rug. By 1915, the Ku Klux Klan had reconstituted itself, and D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation cast the KKK and the Southern cause as just and heroic.

America in this time is often characterized as a melting pot, but it is perhaps more accurately described as a pressure cooker on the verge of exploding. As Hochschild shows, the United States’ entry into the Great War would detonate the nation.

Fearing opposition to the war might cripple industries essential to the war effort or encourage resistance to the draft, Congress passed the Espionage Act (1917) and the Sedition Act (1918), vaguely worded laws that made virtually anything interpreted as opposition to the war a crime. State and local governments quickly followed suit. Soon enough, thousands of Americans found themselves detained by national, state, and local authorities for running afoul of the laws, including one man who questioned the war not in public but during a private conversation. A filmmaker who spent three years in jail for creating a patriotic movie about the American Revolution that was deemed too critical of the United States’ British allies was one of 450 individuals who served sentences of at least one year in prison.

Authorities also saw in the laws the opportunity to finally crack down on labor activists and political agitators. The day the Espionage Act became law, Russian-born anarchist Emma Goldman was arrested for urging young men to resist the draft. She would be sent to prison and eventually deported. Socialist Kate Richards O’Hare joined her in jail, as did Eugene Debs, who had received 6% of the popular vote in the 1912 election as the Socialist Party’s nominee for president. (Despite his incarceration, Debs would go on to win 3.4% of the popular vote for president during the 1920 election.) The laws were also used to undermine organized labor. A prime target was the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), an ambitious union that aimed to unite workers regardless of race, gender, trade, or training behind a militant anti-capitalist political program. Although IWW’s radicalism turned off many potential members, the government still worked hard to crush it, and by the end of the decade, it had nearly been rendered inoperable.

Citizens of the United States in the 1910s may not have enjoyed the full range of rights we are accustomed to today, but the United States’ entry into World War I proved any rights Americans may have assumed they possessed were illusory. The government’s new Military Intelligence branch was used to spy on the nation’s own citizens, with labor unions and immigrants often placed under surveillance. Postmaster General Albert Sidney Burleson used the Espionage Act to censor numerous left-wing, pro-labor, and foreign-language publications by refusing to deliver them through the mail. Conscientious objectors faced cruel and unusual conditions in prison, with many subjected to waterboarding and other forms of torture.

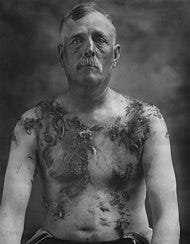

But Hochschild’s most shocking chapters detail the ways in which frenzied pro-war Americans mistreated their fellow citizens. Mob justice often ruled. Pastors who spoke out against the war or who preached pacifism might find their churches burnt down. Someone who refused to buy a war bond might be tarred-and-feathered or dragged through the streets behind an automobile. With the blessings of the Justice Department and Woodrow Wilson himself, as well as funding from wealthy industrialists like Henry Ford, 43-year-old civilian Albert Briggs created the American Protective League (APL), a vigilante group of middle-aged men dedicated to rooting out threats to national security on American soil. Hierarchical in structure and fancying itself as a sort of neighborhood counter-espionage group, the APL—through hundreds of chapters spread across the United States—spied on and arrested those they suspected of disloyalty, purged libraries of unpatriotic books, broke up union gatherings and antiwar rallies with physical force, and beat up dissidents.

An incident in Butte, Montana, in 1917 captures the various undercurrents coursing through this era. Shortly after the United States declared war on Germany, a mining disaster in Butte left over 160 miners dead. Within weeks, IWW organizer Frank Little arrived in Butte to rally the town’s workers to take collective action. Speaking to a crowd numbering in the thousands and consisting of workers from all corners of the world, Little urged defiance. Two weeks later, though, Little would be kidnapped from his hotel room in Montana in the middle of the night, dragged behind a car, and then hanged from a bridge. Following Little’s funeral, armed federal troops occupied the town for the duration of the war. Apparently pleased with the outcome, Vice President Thomas Marshall remarked, “A Little hanging goes a long way.”

With vigilantism loosed throughout the nation, it was an especially dangerous time for Black Americans, who already lived their lives under the constant threat of extra-judicial mob justice. The cruelty white mobs inflicted on Black bodies and Black neighborhoods was horrific. In East St. Louis, a white mob enraged by Blacks who had moved from the South to escape Jim Crow and attain employment as low wage workers in the river town’s industrial plants razed the city’s Black neighborhood, displaced 7,000 Black residents, and murdered an estimated 100 Black people, including children and babies. At Camp Dodge, Iowa, 3,000 Black soldiers—many of whom dutifully joined the war effort to earn the respect of their white countrymen—were ordered to stand without arms in front of a gallows while surrounded by armed white soldiers to witness the lynchings of three Black soldiers accused of rape.

The year 1919 was the worst of all, with white riots erupting in cities throughout the country. In Chicago, an outburst of violence initiated by the death of a Black teenager who had floated into a “Whites Only” section of Lake Michigan left 38 dead and at least 530 seriously wounded. (In some instances, including Chicago and Washington, DC, Black veterans and residents were able to fight back and defend their neighborhoods.) Hochshild concludes his book by recounting the Tulsa Massacre of 1921, when whites launched an all-out assault on the city’s Black population following a confrontation arising from a (likely false) accusation of impropriety leveled against a Black man by a white woman. By the end of the riot, which included the aerial bombardment of Black residents, more than 1,400 businesses (including the business district known as Black Wall Street) and 35 blocks of homes had been turned to rubble. Approximately 4,000 Blacks were arrested. Not a single white person was detained. Scholars believe at least 300 people were killed.

As these examples show, the United States’ war fever did not break with the end of hostilities in 1918. Americans both in and out of government remained highly suspicious of immigrants and labor activists. Local, state, and national governments now had institutions practiced in the arts of oppression and surveillance operated by bureaucrats eager to hone their methods in the field. Millions of young men with combat training returned home to find a more militaristic country. What many of these men couldn’t find, however, were jobs, as wartime economic production had tightened. This also brought White veterans into conflict with the immigrant and Black workers who had taken their places on the assembly line when they went off to war. At the same time, inflation soared, adding to the nation’s economic anxiety. Finally, a devastating influenza pandemic spread around the world, killing more Americans than the war had claimed. The mood of the country lent itself to lawlessness and the abuse of power.

Looming over all this was the communist takeover of Russia, an event many Americans feared would be repeated here by radicalized immigrants led by socialist activists. The Seattle General Strike, which saw 65,000 striking workers shut down the city for five days and organize a kind of counter-government, seemed like the prelude to a communist revolution. After radical anarchists carried out a wave of bombings targeting prominent businessmen and politicians in the spring of 1919, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer—whose own home was destroyed by a blast—began arresting and deporting immigrants with ties to socialist and anarchist groups. Palmer and his aide-de-camp, an up-and-coming Justice Department employee named J. Edgar Hoover (who had devised a nifty little filing system to keep track of the nation’s subversive element) arrested over 3,000 people, deported over 550 immigrants, and confiscated no more than five weapons.

With the nation in the grip of a Red Scare and inflamed by racial violence, General Leonard Wood—who had organized the Rough Riders with Theodore Roosevelt and was seen by many as his heir apparent—began deploying troops under his command to cities to break strikes and augment local vigilante action. Some urban areas were now patrolled by men with automatic weapons, and machine gun nests began popping up on city street corners. Wood (a Republican) and Palmer (a Democrat) both hoped their crackdowns would win them their parties’ presidential nominations in 1920.

But the fever finally did break that year. A wave of violence Palmer had forecast for May Day 1920 never materialized, and Assistant Secretary of Labor Louis Post—who oversaw the Bureau of Immigration—stymied Palmer and Hoover’s deportation initiative. Called before Congress to explain himself, Post successfully defended his actions by demonstrating how Palmer had targeted many innocent people. In the ensuing months, fears of communist agitation dissipated. Despite coming close, neither Wood nor Palmer would become their party’s candidate for president; in fact, Republican nominee Warren Harding went so far as to say too much had been made in recent years about the dangers of Bolshevism.

One may wonder what role Democratic President Woodrow Wilson played during this national hysteria. He does not come across well in Hochshild’s work. Wilson is a complicated figure. A scholarly president, he was one of era’s great progressives, the first president who seemed to believe government could be used as a tool to achieve social and economic justice. Yet he was also an avowed racist (a legacy that has severely diminished his reputation in recent years) and a haughty, pretentious executive who often found politics beneath him. Wilson successfully ran for re-election in 1916 by reminding voters he had kept the country out of World War I. But with Britain and France on the verge of losing in 1917 and with it their ability to pay off the debts they owed to the American bankers and industrialists who were financing their war effort, Wilson reluctantly but righteously led the country into war. When he learned of abuses of power or instances of mob violence, he often complained to officials but rarely ordered them to do anything about it; it was almost as though such events were too ugly for his refined character to dwell upon and beneath the office of the president to deal with. A poor negotiator, he failed to realize his vision of world peace abroad and at home. While campaigning for the United States to join the League of Nations in 1919, he suffered a series of strokes that left him largely incapacitated for the rest of his presidency. Wilson had hoped the Great War would have made the world safe for democracy, but by drawing the United States into the conflict, he created the conditions that nearly led to the destruction of democracy in America. His second term in office must be ranked as one of the worst presidential terms in American history.

Hochshild does an excellent job leading readers month-by-month through this terrible epoch in American history. As a work of narrative history full of biographical sketches and arresting case studies, armchair historians will breeze through the book. As an academic history, however, it comes up short, as it favors storytelling over a more analytical framework. (I’m not sure why it’s lacking in-text annotations.) It also doesn’t reveal much about its subject that those who have studied the topic before wouldn’t know, although the story of Leo Wendell/”L.M. Ward,” an undercover government agent who infiltrated labor unions and provoked them into confrontations with law enforcement, is a fresh piece of research. Still, this is a story Americans have tended either to ignore or gloss over. To see its many threads brought together in one place and then developed in depth is to behold a nightmare in its totality. Readers who are unfamiliar with the era will be shocked by its revelations.

American Midnight is also an important book for Americans to read right now, as it visits a time like ours when democracy seems imperiled. Forces that were at work between 1917 and 1921—nativism, racism, xenophobia, economic anxiety, fears about socialism, the militarization of police—exert a powerful influence over American society today. Demagogues scoff at the rule of law; endorse brute, strong-arm tactics; denounce those who stand up for the marginalized or who appear insufficiently patriotic; and prey off people’s fears and anxieties. Two years ago, these forces fueled a white riot at the heart of our nation’s democracy.

Some may be tempted to look at this book and argue that no matter how bad things are today, they at least aren’t as bad as things were in the late 1910s. That’s a fair reaction. The United States has made tremendous racial progress over the past one hundred years. A social welfare system is in place to aid those who fall on hard times. We have a much more robust system of individual rights now, and there are a litany of organizations ready to assist people when their civil liberties are violated. The population as a whole just seems more intolerant of intolerance and prepared to raise hell when they detect an injustice. And the most prominent demagogue among us has proven himself to be an incompetent clown whose act is wearing thin.

But I’d also argue current political and social conditions are trending too close to those that prevailed in the late 1910s for comfort. Furthermore, Trump may have been inept, but so was Wilson. It doesn’t take a president to destroy democracy, just one who empowers the wrong people and then looks away. It doesn’t hurt to have a sycophantic Congress willing to whip the masses into a frenzy for political gain, either. And remember this: Few in 1915 may have been able to imagine that the mild-mannered Progressive Era America that would inspire Walt Disney’s version of Main Street, USA, could have ever morphed with a declaration of war into the sort of place that reported those they heard speaking German to authorities, tarred and feathered neighbors for not buying war bonds, burnt down churches served by pacifists, or lynched labor activists for demanding fair pay. Maybe the lesson is that we are never that far from tipping over into madness.

Signals and Noise

“The Supreme Court has just announced it is not able to find out, even with the help of our “crack” FBI, who the leaker was on the R v Wade scandal. They’ll never find out, & it’s important that they do. So, go to the reporter & ask him/her who it was. If not given the answer, put whoever in jail until the answer is given. You might add the publisher and editor to the list. Stop playing games, this leaking cannot be allowed to happen. It won’t take long before the name of this slime is revealed!” And then, a few minutes later: “Arrest the reporter, publisher, editor - you’ll get your answer fast. Stop playing games and wasting time!”—Don Trump on TruthSocial

By Jonathan Chait for New York: “The GOP’s Eternal Return” (“One of the curious things about the recent revolt by far-right House Republicans is that it was led by some of the party’s Trumpiest figures, yet they were essentially insisting that Congress return to the time before Donald Trump. The Republican-rebel demands — that their leaders stage shutdowns and debt-ceiling threats in the service of bug-eyed hysteria over the budget deficit — ‘harken back to the tea-party era,’ noted Politico….When Trump won the nomination in 2016, it was widely believed that the Republican Party’s ideological character had changed in some fundamental way. ‘His surprising election marked a replacement of the GOP’s free-market conservatism’ — exemplified by Paul Ryan — ‘with a more populist, big-government conservatism,’ noted budget hawk Brian Riedl a few years ago, bemoaning the ‘final nail in the tea-party coffin.’ Seeing the nails pop out and the coffin spring back open might seem terribly confusing. What happened to the party’s great philosophical evolution?”

A key player in the upcoming debt ceiling drama: Republican North Carolina Rep. Patrick McHenry

Could a bipartisan solution on the issue of paid leave emerge in this Congress?

“The attorney general has to make sure that not only is justice evenly applied, but the appearances of justice are also satisfactory to the public. And here, I don’t think he had any choice but to appoint a special counsel. And I think that special counsel will do the proper assessment….We have asked for an assessment in the intelligence community of the Mar-a-Lago documents. I think we ought to get that same assessment of the documents found in the think tank as well as the home of President Biden. I’d like to know what these documents were. I’d like to know what the [intelligence community’s] assessment is, whether there was any risk of exposure and what the harm would be and whether any mitigation needs to be done.”—Rep. Adam Schiff, D-CA, commenting on the Biden classified document scandal, wait, did you say Adam “Schiffty” Schiff, the guy who has it out for Trump?

Meanwhile, words tumble speculatively outward from mouth about bad things being bad regarding suspicions of government deep state which we think we don’t know GRRR and…maybe Benghazi somehow?

“Spillage”: That’s a word you’re going to start hearing a lot when it comes to discussions of Biden’s possession of classified documents.

Well this is kinda awkward:

Don Trump’s latest excuse for hoarding classified documents and not giving them back when asked: He didn’t actually have the documents, he just kept the inexpensive folders marked “classified” or “confidential” they came in because they were a “‘cool’ keepsake.”

But Murray Waas reports this about Trump’s classified documents: “On the eve of Donald Trump’s last day in office as President, Trump sent a memo to his attorney general, and also the directors of National Intelligence and the CIA, directing them to declassify thousands of pages of highly classified government papers pertaining to the FBI’s investigation into the Russian Federation’s covert intervention into the 2016 US presidential election to help elect Trump and defeat Hillary Clinton. But Trump was stymied in his efforts to make the records public, leading the outgoing president to rage to aides that the documents would never see the light of day. Now, sources close to Special Counsel Jack Smith’s investigation tell me that prosecutors have questioned at least three people about whether Trump’s frustrations may have been a motive in Trump taking at thousands of pages of presidential papers, a significant number of them classified, from the White House to Mar-A-Largo, in potential violation of federal law. One of these people was compelled to testify before a federal grand jury, the sources say. The sources say that prosecutors appear to believe the episode may be central to determining Trump’s intent for his unauthorized removal from the White House of the papers. Insight into the president’s frame of mind—his intent and motivation, are likely to be the foundational building blocks of any case that the special counsel considers seeking against Trump.”

The week in George Santos news:

Jacqueline Sweet reports for Patch that in 2016, Santos (operating under the name Anthony Devolder) promised to help a disabled vet raise $3,000 through his “pet charity” to pay for surgery to remove a tumor that had developed on the vet’s service dog. Santos never gave the vet the money and the dog died. Santos denies the story. The vet kept a record of the text messages.

Records show Santos’ mother—whom he claims died as a result of being near Ground Zero on 9/11—wasn’t even in the United States on September 11, 2001.

Santos denied he ever performed as a drag queen but photographic evidence suggests otherwise.

Santos appeared to claim on his Wikipedia page in 2011 that he appeared on Hannah Montana. (I’ll give him a pass on this one because he was twenty-three years old at the time and if Wikipedia had existed when I was that age, I probably would have made my own Wikipedia page and claimed to have appeared on ALF as a kid or something like that.)

By Molly Jong-Fast for Vanity Fair: “The Not Particularly Talented Mr. Santos” (“While Santos may take lying to another level, his willingness to deceive the public for power—along with Republicans tolerating or even excusing such behavior—isn’t out of character with today’s GOP. Remember, McCarthy, along with 138 other House Republicans, were willing to overturn the will of the American people to validate Trump’s ‘stolen’ election lies, while also looking the other way for four years as the former president made more than 30,000 false or misleading claims. The message Republicans sent even before Santos is that lying to Americans is acceptable if it’s in the pursuit of power.”)

By David Graham of The Atlantic: “The George Santos Saga Isn’t (Just) Funny” (“If you’re unable to laugh at these stories, you should check your pulse. But if you’re only laughing at them, you should check your head. The Santos story is funny, but a real danger exists that the public might allow its amusement to eclipse the horror of such a candidate reaching office and the consequences for Congress and the American political system’s remaining shreds of repute.”)

And Jon Stewart: “The thing we have to be careful of, and I always caution myself on this and I ran into this trouble with Trump, is we cannot mistake absurdity for lack of danger because it takes people with no shame to do shameful things.”

Republicans will place Marjorie Taylor Greene on the (am I reading this right?) Homeland Security Committee? And George Santos landed on the the Small Business Committee? Isn’t that like putting the Duke Boys on the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee? Or a congressman from an oil rich district on the Environment Comm—oh wait, I get it now…

For some reason, according to public records, Republicans have quit checking into the hotel located in the Old Post Office on Pennsylvania Avenue in downtown DC. It’s a Waldorf Astoria. I’ve heard those are nice. Still, only $2000 since June. Weird, because they dropped $670,000 at the place back in 2018 when it was a Trump International Hotel.

Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema gave each other a high five at Davos for saving the filibuster.

A recent poll of Marylanders found that former Republican Maryland Governor Larry Hogan left office this week with a 77% approval rating. (Joe Biden’s approval in that same poll: 58%.) Even more interesting: Hogan’s approval among Democrats is 81%, fascinating because more Democrats approve of Hogan than Republicans and because that number is identical to Biden’s approval rating among Democrats.

So this runs counter to your standard social media narrative: The 1/6 Committee’s final report focused on Don Trump’s culpability in the insurrection, but in doing so they avoided a number of other topics, including the actions of tech companies in the weeks preceding the riot. Those findings are beginning to leak, and what we’re learning is employees at tech platforms like Twitter were warning their bosses that violent rhetoric violating the platforms’ own regulations concerning such speech was spreading through their networks but company heads were afraid to do anything about it so as not to draw the wrath of conservative politicians. This doesn’t fit in with the narrative that a woke liberal mob is successfully intimidating tech companies.

By Nikki McCann Ramirez, for Rolling Stone: “Students Can Carry Guns at the University of Texas — But They Can’t Use TikTok” (“While students and faculty, under the guise of their own and the university’s safety, will no longer be allowed to access TikTok via university WiFi, under Abbott’s governance they can still carry a firearm on campus. Texas’ “campus carry” laws permit students to carry concealed handguns on campus, including in classrooms.”)

A Wall Street Journal study has found the rate of inflation over the past six months is on par with the average annual pre-pandemic rate of inflation.

Despite an increase in organizing efforts, union membership in the United States dropped to a four-decade low of 10.1% in 2022.

The world has generated $42 trillion in wealth since 2020. The wealthiest 1% have acquired 2/3 of that new wealth.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s far-right Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, in a recorded conversation about how far-right voters would still support him even if he actively worked against the LGBTQ community, said, “I’m a fascist homophobe, but I’m a man of my word.” Jonathan Guyer of Vox fills readers in on Israel’s new far-right government.

The Economist has a good profile of the situation in the strategically important nation of Turkey, where out of control inflation has eroded popular support for President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Analysts, however, worry Erdogan won’t hand over control of the country if he loses an election that is expected to be held in May.

Jacinda Ardern is stepping down as prime minister of New Zealand.

China’s population has started to shrink, the first time that has happened since Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward resulted in widespread famine and death in the 1960s. There is little belief China will be able to reverse the trend, meaning in a few decades the country will lack the workers to sustain its economic growth and care for its elderly population.

Vincent’s Picks: The Traitors

Confession: I watch Survivor. The granddaddy of competitive reality TV is occasionally an interesting sociological experiment, but honestly, it’s more compelling simply as a game. Yes, the show peaked in popularity in the mid-00s, but in terms of gameplay, Survivor was probably at its best in the mid-to-late 10s, when most of its contestants were fans and students of the competition. (The show’s post-pandemic editions have underwhelmed.) The only other competitive reality series I’ve ever watched with regularity was The Amazing Race, which has bounced around so much on CBS’s schedule that I’ve lost track of it. The Amazing Race is enjoyable as a wholesome travelogue, but as a cerebral experience, it can’t compare with Survivor. On The Amazing Race, your objective is simply to finish each leg of the race as fast as you can; on Survivor, contestants have to vote out their fellow contestants one-by-one so that they are the last contestant standing, a self-interested pursuit that requires cooperation and that rewards players who can think multiple moves ahead.

I’ve tried watching other competitive reality TV shows, but I’ve found most of them either contrived or too catty. None have matched Survivor, until perhaps now. Peacock is streaming a new 10-episode series called The Traitors, and while it still has a lot to prove, it has the potential to become a great game show.

Here’s the premise: Twenty contestants are brought to a castle in the Scottish highlands, three of whom are secretly “Traitors” who together eliminate/“murder” one of the seventeen remaining “Faithful” every night by secret ballot. It is the Faithfuls’ job to ferret out the Traitors among them. Every evening, the players gather to discuss and then “banish” someone whom they believe is a Traitor. The banished player must then reveal whether they are a Traitor or a Faithful. Then, if all the Traitors have not been exposed, the Traitors strike again. If a Traitor makes it all the way to the end of the game, they win the $250,000 pot; if not, the remaining Faithful split the cash prize. If that sounds a bit like another reality show called The Mole, note there’s one key difference: Unlike The Mole, whose subversive agent is unknown to the audience, viewers of The Traitors know the identities of the Traitors and are privy to their planning.

For its premiere season, the contestants on The Traitors are split evenly between a bunch of unknowns and a group of reality TV veterans like Brandi Glanville of The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, Cirie Fields of Survivor, and Rachel Reilly of Big Brother/The Amazing Race, plus, for some reason, Olympic swimmer Ryan Lochte. The show is hosted by actor Alan Cumming in a fabulously dapper tartan wardrobe. Cumming, who has been prepping for this job ever since he began introducing Masterpiece Mystery! on PBS fifteen years ago, is campy as all get-out in the role. The Traitors is basically an elaborate “Murder Game,” and Cumming is acutely aware of how incongruous those words are.

What makes The Traitors so addictive, however (beyond the fact every episode ends on a cliffhanger that immediately leads you to watch the first fifteen minutes of the next episode), is its strategic intrigue. The Faithful must search for clues to the Traitors’ identities while convincing their fellow Faithfuls they are trustworthy. The Traitors, on the other hand, need to methodically eliminate players without drawing the suspicions of their fellow contestants. They could, of course, banish those who suspect them, but that would be too obvious. As an act of misdirection, a trickier move would be to vote out a Faithful suspected by another Faithful. Knowing that’s a potential move, however, may persuade the Faithfuls to keep their hunches to themselves. Traitors are also likely to keep players in the game whom other players already suspect. And there’s nothing that keeps a Traitor from throwing another Traitor under the bus in an attempt to prove their “faithfulness.” Why, after all, would a Traitor eliminate a co-conspirator? You’ll constantly be racking your brain trying to figure out what everyone’s next move should be.

Frankly, I have no idea what an optimal strategy for either Faithfuls or Traitors might be, and I don’t think the contestants in this first edition figured that out either. It may be there isn’t one—the paranoia is so heavy on this show that non-suspicious behavior is at times suspicious—but I want to watch more seasons to see if future players can discover one. If a second season is greenlit, the show’s producers should tighten up some features of the gameplay. They ought to get rid of the reality show veterans (who are accustomed to on-screen machinations), make sure it’s clear the Traitors and the entry order for the morning breakfast (when the banished are revealed, with those considered by the Traitors for elimination arriving last to build suspense for the viewers) are randomly selected, and change the in-episode challenges (which are used to build the value of the pot) so they actually affect the game. It’s clear The Traitors is still a work in progress, but it definitely has potential as a competitive show.

Now, if you’re not a fan of competitive reality TV, leave this series alone. And I should warn those who are interested in watching it that The Traitors can get mean, cutthroat, and emotionally manipulative. It’s very reminiscent of early seasons of Survivor, when players took any move that disadvantaged them personally rather than accepting it as part of the game. (Today’s Survivor players will often commend their fellow players for blindsiding them, even when that results in their elimination.) At times the show can be hard to watch: Some players’ toxicity is unnecessarily off the charts, and on more than one occasion—and especially at the end—I worried about the emotional well-being of the contestants. One thing this show makes abundantly clear is that dishonesty is a terrible burden to bear and that we as humans crave trust.

But, as multiple contestants on The Traitors point out, it’s just a game, and future contestants should remember that. No one’s really getting murdered, the host—who won a Tony Award for playing the master of ceremonies in Cabaret—is quoting Shakespeare and making bad puns while wearing a hot pink kilt, and if you can’t spot the sucker, it’s probably you. The Traitors is supposed to be fun and good (that’s a reality show reference) and for the most part it succeeds at that. A fair warning, though: Give yourself a ten hour bloc to watch it, because once you start, you won’t stop until every traitor has been revealed.

![American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy's Forgotten Crisis [Book] American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy's Forgotten Crisis [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!xRFx!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3a804d28-11ba-4ec3-a6c4-b6a6e217f08d_488x488.jpeg)